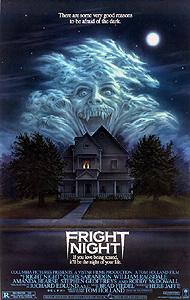

Fright Night (1985) ***

Fright Night (1985) ***

It should be obvious by now that there’s a certain amount of nostalgia behind what I do here, both direct and vicarious. I mean, a few weeks ago, when I could have gone out to a first-run theater to catch Piranha 3-D or The Last Exorcism, I drove all the way to Pittsburgh instead for a two-night marathon of stylistically obsolete stuff that with just two exceptions was released years before I was born. With 40 now visible on the horizon, it occurs to me that I’ve seen several waves of nostalgia come and go, with varying degrees of social impact, and that I find the ones that failed to gain traction more interesting on the whole than those that captured a large share of the collective imagination. Fright Night is an artifact of one such failed nostalgia trip, one of a handful of monster movies that rose up in the early-to-mid-80’s as a little-heeded eulogy to earlier styles that had not only been driven to virtual extinction in the theater, but were finally being chased from their refuge on late-night TV by the profitable pestilence of the infomercial. It is far more conscious of its eulogistic business, however, than such contemporaries as Strange Invaders or the deeply confused Saturday the 14th, not to mention more serious in its intentions as a horror movie. When one of Fright Night’s reluctant heroes— a UHF television horror host whose program just got shitcanned for lack of ratings— grouses that the youth no longer care about traditional bogeymen like vampires, caring only for “demented madmen in ski masks hacking up young virgins,” he seems to be laying bare writer/director Tom Holland’s main motivation for making this movie. That being so, it’s ironic that what most diminishes Fright Night in retrospect is its dogged determination to show that it’s hip to the 80’s despite its old-fashioned subject matter. By striving so hard to be up to date, it becomes far more dated than the decades-older films to which it pays tribute.

Fright Night establishes which segment of the genre’s history it has come both to praise and to bury in what seemed at the time like an exceedingly clever way. High school sweethearts Charlie Brewster (William Ragsdale, from The Reaping and Screams of a Winter Night) and Amy Peterson (Amanda Bearse) are up in the boy’s bedroom, making out when they’re supposed to be working on their trigonometry homework. In the background, Charlie’s TV set is tuned to “Fright Night,” the local UHF station’s late-night spook show, which is playing an old Peter Vincent movie. Vincent (Roddy McDowall, of Cutting Class and It!) is rather like this fictional universe’s answer to Peter Cushing— which is to say that he’s basically a caricature of how Cushing might have been perceived by a generation of horror fans whose nightmares were haunted more by Michael Myers and Jason Voorhees than by Count Dracula and the Frankenstein monster. He’s also the host of “Fright Night,” which by itself should tell you how far his star has fallen since the days when he could headline movies like Blood Castle and Orgy of the Damned. Neither Peter Vincent’s has-been-hood nor Charlie and Amy’s somewhat contentious and indecisive groping is what’s really important now, however. No, what’s important right now is the two men (Chris Sarandon, from Bordello of Blood and The Sentinel, and House II: The Second Story’s Jonathan Stark) loading an antique coffin (among other, more traditional furnishings) into the cellar of the long-unoccupied house next door to the Brewster place. Charlie happens to spot them just when he’s finished convincing his girlfriend to quit stringing him along and climb into bed already, and it sparks an evening-ending argument between the two kids when he suddenly can’t pull his attention away from the new neighbors to focus it on the half-naked girl under his coverlet. Amy storms out, and in all the commotion attendant upon trying to stop her, Charlie almost doesn’t notice the anchorman on the TV news (which his mother [Dorothy Fielding] is watching downstairs) reporting a recently discovered murder in this normally quiet little town. You can bet it’ll be the first thing he thinks of later, though, when he spots the older and more stylish of the new guys next door sprouting fangs and talons while getting it on with a girl Charlie has never seen before. And freaksome as that is, it isn’t half as scary as the fact that Charlie’s apparently vampiric neighbor plainly spotted him right back.

Charlie’s response to these alarming developments reflects poorly, to put it mildly, on his capacity for thinking strategically. Take, for instance, the way he spies on the men next door when he observes them carrying what looks very much like a dead body wrapped in garbage bags from the cellar to their Jeep the following night. Even before his mother comes outside to blow his cover, Charlie could not be any more obvious if he were trying to get caught, and there’s no question but that the vampire and his buff, surfer-dude Renfield know exactly where he is and exactly what he’s doing. Charlie’s bid to involve the police after what he takes to be a second girl’s murder is an even bigger failure. Sure, he gets Detective Lennox (Tales from the Hood’s Art Evans) to come out to the house and investigate, and Lennox even has Billy Cole (the surfer-dude Renfield) let him in to look the place over. But when it becomes clear that there’s nothing to see in the above-ground portion of the house, and that Lennox accepts Cole’s story that Jerry Dandridge (the vampire) is out of town for the day on business, Charlie overplays the living shit out of his hand by urging the detective to go down to the basement. When Lennox and Cole both ask what Charlie thinks the cop is going to see in the cellar, Brewster foolishly blurts out: “A coffin! And you’ll find Jerry Dandridge sleeping the sleep of the undead inside!” Lennox, as you might imagine, decides at that point that enough is enough, and lets it be known that he will not be taking Charlie’s calls in the future. Even Charlie’s efforts to enlist the aid of his friends accomplishes nothing but to convince them that he’s gone bonkers. Amy breaks up with him, and although school weirdo “Evil” Ed Thompson (Stephen Geoffreys, of 976-EVIL and The Chair) humors him to the extent of coaching him on vampire lore (this is a small but serious error, by the way; surely an inveterate horror fan like Charlie already knows about crosses, garlic, holy water, and stakes through the heart), it’s obvious that Ed takes Charlie no more seriously than did Lennox. All of which adds up to a worrisome state of affairs when Charlie’s mom invites Dandridge over for a visit that evening— as Evil Ed only just got finished explaining, the surest line of defense against a vampire is that it can’t enter a home unless it is invited in.

Dandridge makes his first move on Charlie that very night. Under the circumstances, Jerry would prefer not to kill the kid next door (after all, that might make Lennox think something was up after all), but he wants the boy to know in no uncertain terms that he’s completely prepared to do it if the snooping and interference don’t stop immediately. Slipping into the house in the form of a fogbank, the vampire first jams Mrs. Brewster’s bedroom door shut, then proceeds to Charlie’s room. Charlie refuses to be intimidated, however, and pretty soon it’s looking like Dandridge did the smart thing by not eating dinner yet. But the racket generated by Charlie’s struggles awakens his mother, and Dandridge withdraws to seek a cleaner kill some other time.

If Charlie is going to be doing the Jonathan Harker thing from now on, then obviously it behooves him to find himself a Professor Van Helsing— and it just so happens that there’s a man right there in town who used to make his living slaying vampires, right? Charlie drops by the local TV station, and luckily catches Peter Vincent on his way out the door. The “Great Vampire Killer” is in no mood to talk just now, though, for Charlie has arrived immediately after Vincent was handed his pink slip by the program directors, who have concluded that there must be some more profitable use of his timeslot than reruns of monster movies from the 1960’s. Vincent finds himself in an even bigger hurry to get gone once he hears what Charlie wants from him, understandably assuming that the boy is totally out of his mind. The old actor is far from finished with Charlie Brewster, however, for a day or two later, Amy and Evil Ed come to see Vincent at his apartment, begging his help (and offering $500 that he sorely needs to placate his landlady) in straightening Charlie out. They had visited Charlie that afternoon, you see, and found him whittling stakes in a crucifix- and garlic-festooned room, talking of breaking into the house next door and killing the vampire before it killed him. Amy thinks she can persuade Jerry Dandridge to permit Vincent to administer to him some manner of test in order to demonstrate to Charlie that he’s human after all. With no less an authority than Peter Vincent, Vampire Killer, signing off on Jerry’s humanity, Charlie will finally have to admit that he’s been mistaken, deluded, or whatever you want to call it, right? Vincent and Dandridge both assent to Amy’s proposal, although Dandridge claims that his convictions as a born-again Christian rule out the use of either crosses or holy water. Not a problem, promises Vincent. He’ll just fill up one of his old movie-prop flasks with tap water, and tell Charlie that he had it blessed. The whole gang comes round an hour or so after sunset that evening, and Dandridge quaffs Vincent’s “holy water” right in front of Charlie with no ill effects. However, when the vain old actor produces a mirror from his coat pocket to aid in straightening his hair, he notices to his astonishment that Jerry casts no reflection in the glass. And Jerry, sharp as always, notices him noticing. Of course you realize this means war…

Fright Night represents, for the most part, a charmingly successful compromise between two contrary creative impulses. It is in many respects the most traditional vampire movie since the early 1970’s, but it’s also a self-aware commentary on the decline of traditional vampire movies as a pop-culture touchstone— and it gets the job done in both modes, if sometimes a bit awkwardly. Fright Night kicks it old-school by interposing its vampire between a pair of young lovers, setting up the girl as the story’s featured victim and sending the boy scrambling to recruit some savant to help him vanquish the monster. It also looks backward by shying away from none of the “unrealistic” magical trappings of vampirism that more recent films have tended to eschew— it dawned on me while I was revisiting this movie that I could not remember the last time I saw a vampire turn into a wolf or a cloud of mist. Fright Night is probably nowhere more old-fashioned, though, than in its steadfast refusal to romanticize Jerry Dandridge in any serious way, or to seek any audience sympathy for him whatsoever. Even when Amy is far enough under Jerry’s sway to have retractable fangs and an intermittent bloodlust of her own, she recognizes herself as nothing more than Dandridge’s victim; in one scene, Amy reproaches Charlie for failing to keep her safe just seconds before lunging for his throat! Chris Sarandon is a major asset here, making for a very plausible 80’s update of the Polidori-derived conception of the vampire as a diabolical seducer who for all his superficial charm is nevertheless a creature of unalloyed evil. Fright Night’s only really damaging misstep as a vampire story in the Georgian-Victorian tradition is the lip-service it pays to the “Dark Shadows”-ish conceit that Amy looks more or less exactly like somebody from Dandridge’s past. Without the moral ambiguity of Blacula or the John Badham-Frank Langella Dracula, the doubling serves no purpose, and indeed Fright Night never really does anything with it.

The other side of Fright Night is embodied mostly in the person of Peter Vincent. The real Peter Vincent could not be further removed from the characters he played in his movies, or from the man he needs to be when Dandridge gets serious about keeping his secret contained. He’s pompous, venal, and cowardly, with a large but fragile ego and just enough innate goodness to become wracked with guilt over the failings exposed by his first encounter with a real vampire. Feet, hell— the clay in Charlie Brewster’s idol goes all the way up to the armpits! And although it falls to Vincent to voice Tom Holland’s lament about modern young people’s philistine tastes in horror movies, there is implicit in that characterization an admission that philistinism did not kill off Hammer, Amicus, and the rest all by itself. At least equally important in the eclipse of horror as the kids of the 60’s knew it was the growing unpersuasiveness of the orderly, black-and-white moral universe presupposed by those films, and of the paternalistic infallibility of their heroes. It wasn’t vampires that had become unbelievable by the mid-1970’s, but rather Professor Van Helsing, and Fright Night’s action owns up to that fact even if the characters’ dialogue denies it. The vampire here is real— it’s the Great Vampire Killer who’s a phony.

Unfortunately, Holland was not content with— or perhaps did not trust in the appeal of— just the degree of modernity conferred automatically by the contemporary setting and the subversive handling of Peter Vincent. No, Fright Night would have to compete with the likes of An American Werewolf in London and The Terminator along with the legions of slasher flicks on which it casts aspersions, and the combination of its attitude and its subject matter arguably meant that it was competing with a handicap right out of the gate. So in what looks like an overly strident bid to assert its modernity, this movie gives us a state-of-the-art electronic score… which started to sound uncomfortably like 1985 already by about 1987. It gives us an overlong but exquisitely detailed wolf-to-man transformation scene and a big set-piece in which Dandridge attacks Amy in a dance club… which do little but to remind one of the rather better movies that inspired those bits. It gives us a new and more grotesque prosthetic makeup design virtually every time a vampire (or half-vampire, as the case may be) shows his or her true colors… which accomplishes nothing but to make one wish the filmmakers would pick a look and stick with it. None of that stuff was necessary, and Fright Night does itself no favors by trying so excessively hard.

There’s one last thing about Fright Night that I want to mention before wrapping up, the rich vein of interest that it holds for gay-themes enthusiasts. This being a mainstream horror film from the height of the Reagan age, there’s little or nothing here that could not be read another way, but the hints are both unusually numerous and unusually blatant for this era. To begin with, it’s worth pointing out the number of cast-members who were homosexual in real life: Roddy McDowall, Amanda Bearse, Stephen Geoffreys (known to connoisseurs of 90’s gay porn as Sam Ritter). But more importantly, it is very strongly implied that Jerry Dandridge is every bit as bisexual as his female counterparts had been in movies dating back throughout the last fifteen years. Dandridge and Billy Cole are physically affectionate with each other in a way that goes rather beyond what one expects between straight male roommates— or indeed between master vampires and their Renfields. And given the more or less explicit equation between sex and blood-drinking that had established itself within vampire fiction generally by the mid-80’s (and with which Fright Night falls completely into line during Dandridge’s attacks on female characters), it is suggestive to say the least when the TV news reports what we later recognize as vampire attacks on males. Then there’s Evil Ed. I’ve drawn parallels already between Fright Night and the various versions of Dracula, but the most remarkable one is that Evil Ed is this movie’s Lucy Westenra. As with Dracula and Lucy, Dandridge doesn’t simply kill and transform Ed— he seduces him. And although that seduction is not overtly sexual, being couched instead primarily in terms of power and acceptance, there is absolutely no mistaking it for anything but a seduction. Furthermore, the specific forms of power and acceptance that Jerry offers are wide open to a queer interpretation. What the vampire promises is the companionship of someone who understands “what it’s like to be different,” and an impregnable defense against the harassment and bullying that the boy faces from his peers. Now there are plenty of criteria whereby a teenage boy could be judged “different”— and Evil Ed satisfies just about all of them— but non-heterosexuality would fit the bill as well as any. Similarly, although gay teens surely have no monopoly on peer victimization, there’s no clear reason to assume that homophobia isn’t one of the petty cruelties bedeviling Ed specifically. Factor in the uncharacteristically gentle embrace in which Jerry enfolds Ed while biting him (none of the girls Dandridge eats have it that good— not even Amy), and this scene alone puts Fright Night in company with A Nightmare on Elm Street 2: Freddy’s Revenge as an example of how horror in the 80’s was beginning to come to grips with the increasing visibility of homosexuality, and to treat it as something more than just an easy punchline or an exploitable angle for sensationalism.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact