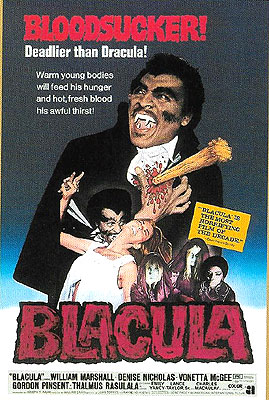

Blacula (1972) ***½

Blacula (1972) ***½

What we have here is, to the best of my knowledge, the world’s first blaxploitation horror movie. The pioneering efforts of Blacula’s creators made possible such lofty artistic achievements as Black Werewolf, Dr. Black and Mr. Hyde, and everyone’s favorite, Blackenstein. (How is it possible that no one thought to do The Phantom of the Apollo?) Given what would come in its wake, the truly astonishing thing about Blacula is how seriously good it is when its engine is running smoothly. There are, as we shall see, some really groan-worthy moments in this film, but on the whole, it is a well-executed, imaginative, and intelligent movie.

Not that you’d ever figure that out from the first three scenes, of course. Blacula begins in Transylvania (naturally) in the year 1780. Mamuwalde (William Marshall, from Abby and The Boston Strangler) and his rivetingly gorgeous wife Luva (Vonetta McGee, who would later appear in Shaft in Africa and Repo Man), the leaders of Africa’s Eboni tribe (it’s pronounced “ay-BOW-nee,” but it’s going to take more than that to stop my eyes from rolling at that one) have come to the castle of Count Dracula (Charles Macaulay, from Tower of London and The Twilight People) on a vital diplomatic mission. Mamuwalde wants to bring his people into the 18th century, and he recognizes that to do so, he will need assistance and cooperation from the West-- and the form of cooperation he wants most is the cessation of the slave trade. Consequently, he has come looking for a patron among the crowned heads of Europe. Such a pity then that the nobleman upon whom Mamuwalde has pinned his hopes is not only a complete bastard who quite likes the slave trade (“I would gladly pay money to add your delicious wife to my household,” he says), but a vampire as well. Dracula summons a couple of lackeys to seize Luva, and a fierce struggle between them and Mamuwalde ensues, the African prince’s defeat coming only when Dracula calls in the aid of his harem of female vampires. Incensed by his guests’ resistance, Dracula takes it upon himself to place Mamuwalde under the sway of what the movie posters called “a slavery more vile than any before endured”-- he bites the African prince and makes him into a monster like himself. But that just isn’t quite nasty enough, so the vampire locks Mamuwalde in a coffin in a secret vault beneath his castle, so that he will be tortured forever by his inability to slake his thirst for blood. And just for good measure, he walls up Luva in the vault too.

It’s all pretty silly, but that’s nothing compared to what’s on its way in the next scene. Almost 200 years later, a pair of gay interior decorators arrive at Dracula’s long-abandoned castle to buy up its contents; they figure they can make a fortune from selling furniture and knickknacks from the famous vampire’s estate (though they, of course, do not believe for a second that the stories told about the count are true). And of course, among the treasures the two men take away with them to America is the coffin in which Mamuwalde has been confined for the past two centuries. In what is undoubtedly the stupidest five minutes of the entire film, the decorators (now back at their New York warehouse) mincingly look over the haul that they expect to make them very rich, committing the grave error of hacking the lock off Mamuwalde’s coffin. But before the black decorator (oh, did I mention we’ve got an interracial gay couple here?) can open the coffin, his boyfriend cuts himself on a nail on one of the other crates. While they are distracted by the need to tend to his injury, Mamuwalde rises from the coffin, apparently roused by the smell of blood. He then attacks his “rescuers,” biting both and draining them dry.

So tell me, what do you suppose is going to be the mainspring of this movie’s plot? Mamuwalde is going to meet a woman who suspiciously resembles his dead wife, you say? Good call. It turns out that the black victim numbered among his friends a forensic pathologist called Dr. Gordon Thomas (Thamlus Rasulala, of Cool Breeze and Friday Foster), Dr. Thomas’s assistant/girlfriend Michelle (The Soul of Nigger Charlie’s Denise Nicholas), and another, unattached girl by the name of Tina (Vonetta McGee again). All three come to see their friend’s body before the funeral, and Gordon notices some strange things about it. There is, of course, the huge, deep bite-mark on the neck, which the funeral director wasn’t quite able to conceal despite great effort and ingenuity, but what puzzles Gordon more is the fact that the body seems empty of fluids, even though the mortician claims not to have yet embalmed it. The three friends soon leave the funeral parlor and go their separate ways, and this (in case you hadn’t figured out what would follow from the main characters splitting up) is when Tina first meets Mamuwalde. They almost literally bump into each other on the street, and Tina is terrified by the big, caped stranger’s manner when he reacts to their chance encounter with an explosion of feeling usually reserved for reunions between long-separated lovers. She runs, and Mamuwalde pursues her, but the chase is interrupted when the vampire lunges out into the street in an attempt to cut Tina off and is flattened by a passing taxi. I don’t know about you, but I really wouldn’t want to be the cabby that came between a 200-year-old vampire and the reincarnation of his long-dead wife by running him over. It just seems like it would be a bad scene.

The problem for Tina is that she dropped her purse in the chase, and Mamuwalde has picked it up, learning from the enclosed ID documents Tina’s name, address, and basically everything he needs to track her down (we won’t go into the problems that a man from 1780 might have reading a 20th-century driver’s license). And it looks like Tina kept something in that purse that identified her favorite hangouts, because Mamuwalde shows up the next night at the funk club to which Gordon and Tina have taken Michelle for her birthday. He has come bearing the purse, and he is very gracious and gentlemanly about returning it to her, explaining away his odd behavior the night before by telling Tina that she looks uncannily like his wife, whom he “lost not long ago.” I tell you, man-- you want to get the chicks, just watch this guy in action and take good notes. The only really discordant note in Mamuwalde’s performance is the way in which he recoils at the flashbulbs of the cameras on the two occasions on which someone takes a picture of him. This is going to be important later, as one of those pictures is going to serve as the final piece of evidence convincing Gordon that there’s a vampire in town, while getting the club waitress who took it killed and vampirized herself. (We won’t go into the difficulties a man from 1780 might have in recognizing the significance of a camera, either.)

There are basically two parallel plots from this point on. First, Gordon works on solving the mystery behind the bloodless bodies that have begun to show up with alarming frequency in the precinct served by his crime lab. At the same time, Mamuwalde and Tina are growing closer and closer together. Gordon and Mamuwalde both have their big breakthroughs at about the same time, the doctor figuring out that what he’s looking for is a vampire while Mamuwalde sells the love-struck Tina on joining him in eternal unlife. The difficult position in which both sides are thus placed should be obvious, and events move swiftly from this point until the inevitable showdown in the vampire’s lair.

It is in this final phase of the film that Blacula’s strengths really come to the fore. The first and most obvious is the portrayal of the vampire himself. I can’t be quite certain, because there are numerous gaps in my vampire movie knowledge running from about 1950 to about 1975, but we may be looking at the first-ever cinematic treatment of the vampire as tragic anti-hero. Mamuwalde was a noble and honorable man, and he is just as noble and honorable as a vampire. But the undead Mamuwalde is no less a monster for all that; he remains a deadly, merciless predator, a scourge that must be destroyed. Worst of all, from the character’s own perspective, Mamuwalde knows he is evil, yet he is powerless to do anything about it-- a biological imperative is a biological imperative, after all. And because William Marshall is such a good actor, in an understated, aloof way, the viewer is able to read even more of this internal conflict into the movie than its script explicitly presents. The other main source of Blacula’s unexpected power is the way in which Tina’s relationship with the vampire is handled. Most vampire movies hinge on the vampire’s seduction of the female lead; the convention goes all the way back to Stoker’s Dracula, if not farther still, and equally conventional is the dynamic of that seduction. The vampire is usually depicted as exerting some kind of supernatural influence over the woman, bringing her under his power and preventing her from grasping the consequences of what she’s doing until it’s much too late, and she can be saved only by the timely intervention of the other (usually male) characters. But that is absolutely not what happens here. Tina is never, at any point, under Mamuwalde’s power. Rather, she loves him, she believes in him, and she sees the inherent goodness of the man he once was. Her choice to join him is one she makes consciously, for herself, and if it is a bad, mistaken, self-destructive choice, it is no different from the choice that many real-world women make to be or stay with dangerous, but fully human, men. If Tina is blind to the evil that Mamuwalde must do (and that she herself will be forced to do should she go with him), it is no different from the blindness that afflicts the thousands of women who attach themselves to abusive or criminal men in real life. Gordon and Michelle’s efforts to save Tina thus take on a very different light from the efforts of their counterparts in more conventional vampire films. Gordon and Michelle are, like Mamuwalde and Tina, in a no-win situation-- if they fail, Tina will become a vampire and they will be forced to destroy her too; but if they succeed, they will have taken from their closest friend what has become the dearest thing in her life and they will be forced to live with that knowledge for the rest of theirs. Who’d have expected this kind of thoughtful, nuanced storytelling could be hidden in a movie called Blacula?

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact