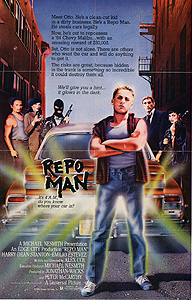

Repo Man (1984) ****

Repo Man (1984) ****

It always feels a little weird to write about a cult movie for which I’m not a member of the cult. These films mean a great deal to people, after all, and when they don’t mean anything to me, it sometimes leaves me suspicious of my own judgement, like there must be something I missed. That’s especially true of Repo Man, because by any reasonable assessment, I should be a Repo Man cultist. It’s a snidely satirical sci-fi movie with punk rock attitude, set (to begin with, anyway) in exactly the oft-ignored subspecies of punk scene that gave me my start in the counterculture; why the hell wouldn’t I love something like that? Furthermore, Repo Man is just amazingly good at what it does, standing as one of the truly great off-kilter comedies of my lifetime. And yet for some reason, despite its obvious brilliance and despite its equally obvious relevance to my own life, I’ve simply never become a fan of this movie the way so many people do upon being exposed to it for the first time. What’s really weird is that Repo Man is the only film I can think of that I relate to this way, fully recognizing and appreciating all of its charms, even as they sort of slide off me without leaving much impression.

Somewhere to the east of the close approximation of nowhere that is Goffs, Arizona, nuclear physicist J. Frank Parnell (Fox Harris, of Alienator and Hollywood Chainsaw Hookers) gets pulled over by a traffic cop. There really isn’t a word for the way Parnell was driving, but it’s no surprise that anyone charged with upholding the rules of the road would take issue with it. Actually, we don’t know just yet that Parnell is a scientist— hell, we don’t even know that his name is Parnell. Indeed, the only thing we might know about him is that he’s been making his way methodically westward from Los Alamos, New Mexico, and the only way we’d put even that much together is by intuiting the significance behind the montage of highway maps that plays beneath the opening credits. In any case, the cop concludes almost at once that Parnell is drunk, stoned, or crazy, and takes it upon himself to search the trunk of the physicist’s decrepit 1964 Chevy Malibu for contraband. This turns out to be a really bad idea. Whatever’s in the trunk disintegrates the patrolman right down to his riding boots as soon as he gets the lid fully lifted. Conspiracy buffs might want to start pondering the associations of little New Mexico desert towns like Los Alamos and Roswell right about now.

Meanwhile, in Los Angeles, eighteen-year-old (never mind what it says on his driver’s license) punk rocker Otto (Emilio Estevez, from Maximum Overdrive and Nightmares) is getting fired from his super-shitty supermarket stock-boy job. So, for that matter, is his arch-nebbish friend, Kevin (Circle Jerks bass-player Zander Schloss). A further disruption to Otto’s life occurs that night during a party at Kevin’s house. One of the other guests is Duke (Night of the Comet’s Dick Rude), an old pal of Otto’s who was just released from juvenile jail, and when Otto interrupts an unauthorized tryst in Kevin’s parents’ bedroom to get beers for himself and his girlfriend, Debbie (Jennifer Balgobin, from Cherry 2000 and Dr. Caligari), he returns to find Duke getting it on with her in his stead. With no job, no girlfriend, and a great, big, stinky betrayal from Duke to top it all off, Otto figures this is as good a time as any to get as far gone from LA as he can. Now it happens that some months ago, Otto’s father (Jonathon Hugger) offered to send him to Europe for a while if he would go back to college and stick with it this time. That gets the boy thinking that maybe he can prevail upon his folks to pack him off across the Atlantic early in exchange for an IOU to finish school. There’s a rather serious flaw in this plan, however, for Mom (Sharon Gregg) and Dad have become followers of a televangelist called the Reverend Larry (Bruce White), to whom they’ve just given away all the money that might have financed such extravagances.

Nevertheless, Otto soon gets the drastic change of pace he’s craving, from a source he never would have considered. While trudging sullenly through some Hispanic ghetto one afternoon, he is accosted by a man who introduces himself as Bud (Harry Dean Stanton, of Escape from New York and Alien), and asks if Otto would like to make some quick cash. Otto assumes at first that Bud is cruising him, but the stranger’s spiel is in some ways even shadier: he says he urgently needs to get his wife to the hospital, but doesn’t want to leave her car unattended in this crappy neighborhood. What makes that so shady is that there’s no sign of any wife— in need of hospitalization or otherwise— in the car Bud is driving. Still, $25 is $25, and Otto somewhat grudgingly accepts the proposition. As you might expect, the prematurely mangy Cutlass Cruiser belongs to nobody even distantly connected to Bud, and its owners are not a bit happy to see some gringo teenager starting it up. This is not to say that Bud is a car thief, though— or rather, he is, but it’s perfectly legal the way he does it. That’s because he works for the Helping Hand Acceptance Corporation, repossessing cars whose owners have fallen behind on their payments. In fact, so impressed is Bud with Otto’s performance abetting his bank-approved heist that he offers the lad a job with the firm once he and his coworkers have the Oldsmobile securely impounded in the Helping Hand yard. Otto revolts at the notion of becoming a repo man, but as Marlene the dispatcher (Vonetta McGee, from Blacula and The Norliss Tapes) points out when she hands over his $25, the day’s activities mean that he sort of already is one.

Otto’s new coworkers are, with the possible exception of Marlene, some really fucked-up people. Oly the boss (Tom Finnegan, of Alien Nation and Predator 2) is merely cantankerous and openly belligerent toward the people who come in bearing money to reclaim their cars, which in this company makes him the normal one. Bud, with his constant talk of the “Repo Code” (apparently a hodgepodge of misapplied tenets scavenged from chivalry, Bushido, and Isaac Asimov’s Laws of Robotics), fancies himself a sort of reverse Robin Hood. Lite (Sy Richardson, from Fairy Tales and Bad Dreams) is somewhere between a blaxploitation superpimp and the stereotype of the Vietnam-damaged ex-Green Beret. Pletschner the rent-a-cop (Richard Foronjy, of Ghostbusters II and Shark Kill) wants very badly to be Dirty Harry, Paul Kersey, and Travis Bickle all rolled up into one. Miller, the guy who preps the cars for resale (Tracy Walter, from Conan the Destroyer and Cyborg 2), is a borderline-retarded acid casualty who contends that driving lowers your intelligence and that UFOs are time machines from the distant future whose operators are just passing through while ferrying the ancestors of humanity to the distant past. (He also contends that John Wayne was a homosexual, but that’s a separate issue.) And what all of these speed-snorting nutters have in common is a seemingly unquenchable ardor for the sound of their own voices; Otto can’t go anywhere with any of them without being subjected to a constant lecture on the finer points of their very peculiar philosophies.

Otto’s story and J. Frank Parnell’s come together when Parnell reaches Los Angeles. It seems the mysterious, cop-disintegrating cargo in the scientist’s trunk consists of the dead bodies of several extraterrestrials, which Parnell smuggled out of the top-secret military lab where he worked until he went mad under the strain of helping to develop the neutron bomb. He’s been in contact with a dissident organization seeking to expose the cover-up of alien activity on Earth, and it is in LA that he’s supposed to meet up with a girl named Leila (Olivia Barash, from Child of Glass and Grave Secrets) to hand over the carcasses from space. Leila, coincidentally, has just met and struck up an affair with Otto, who set his sights on her while cruising for chicks in a newly repossessed Eldorado convertible. She told Otto all about the business with J. Frank Parnell and the aliens, and soon she even takes him to visit the fruitcake plant that rather aptly serves as a front for her organization. What Leila doesn’t realize is that she and her comrades are being monitored by whatever nefarious government agency is charged with keeping the aliens hidden from the public. Agent Rogersz (Susan Barnes, of Zombie High and They Live), leading the recovery mission, thinks maybe she could use Leila’s carelessness around Otto to lay a trap for her and Parnell. In the meantime, Rogersz has one of her outfit’s front companies put out a repossession order on Parnell’s car, offering a payout big enough to inspire the avarice of every repo man in the city— and to turn the staff at Helping Hand against each other in internecine competition as well. Bud sees Rogersz’s $20,000 as an opportunity to ditch Oly and go into business for himself. Marlene’s motives are murkier, but she certainly doesn’t have the firm’s interests in mind when she hires Bud’s nemeses, car thieves par excellence Napo and Lagarto Rodriguez (Eddie Velez and RoboCop’s Del Zamora), to snag the ancient yet improbably valuable Malibu for her. And as if that weren’t enough, Duke and Debbie (remember them?) have been on an ever-escalating crime spree since Otto cut his ties to them, and although knocking over convenience stores is really more their speed, there’s no reason why they couldn’t trade up to grand theft auto if the incentives were right. There’s one thing you have to wonder about, though. You think maybe driving around town with a trunk packed full of something sufficiently radioactive to vaporize anyone directly exposed to it might not be the smartest way a person could spend their time?

The most striking thing about Repo Man is the way its A-plot and B-plot are installed upside down. Theoretically, this movie is about J. Frank Parnell escaping from Los Alamos with a trunk full of dead aliens, and being chased across the Southwest by Agent Rogersz and her minions. But Parnell isn’t the viewpoint character. Otto is, and Otto spends most of the film in no position to know anything about aliens, mad scientists, or shady government agents. Consequently, throughout the first and second acts, Repo Man’s main story goes on in the background, totally unnoticed by its protagonist. This movie spends the bulk of the running time looking like a strange arthouse character study, and only when Otto is confronted with a chance to repo Parnell’s car does it become obvious that you’ve been giving your attention to the wrong plot thread. I have seen this sort of inversion used elsewhere (something similar figures in one of my favorite episodes of “Buffy the Vampire Slayer,” for example), but never that I can recall with such total commitment. Otto doesn’t merely remain oblivious to the drama steadily enfolding him— he rejects it as a concept. When Leila spins her tale of smuggled alien corpses; when Parnell blathers at him about neutron bombs, lobotomies, and radiation; even when he faces captivity and torture at the hands of Agent Rogersz— Otto simply refuses to acknowledge that any of it has any more basis in reality than a Reverend Larry sermon, Bud’s Repo Code, or Duke’s “I blame society” defense for his self-destructive criminality. Only after he’s been involved in three shootouts and seen Parnell’s car transfigured into an unanswerable refutation of reality as he understands it is Otto willing to grant that in this particular instance, the people he’s been dismissing as credulous loonies are on to something.

That’s an interesting point not just for the completeness with which it allows writer/director Alex Cox to compartmentalize the A-plot from the B-plot, or for the way it facilitates the humorous possibilities of an unaware protagonist. Most comedies built around characters who fail to recognize what’s going on around them get there by making their central figures dense or unobservant. Otto isn’t either of those things, though. Rather, he has overreacted to the eagerness with which everyone around him buys into their favorite form of hogwash by becoming skeptical to the point of nihilism. Otto doesn’t believe in aliens because he doesn’t believe in anything— in fact, he considers the very idea of believing in things to be ridiculous. In that respect if no other, Repo Man remains a punk movie even after Otto drops out of the scene to pursue the purer rush of excitement afforded by stealing cars at the behest of banks for a living. Attitudinally speaking, Otto would fit right in at Suburbia’s TR house. That turns the ending into something like a backwards Close Encounters of the Third Kind with regard to Otto. In the Spielberg movie, those whom the aliens rewarded, if you can call it that, were the ones who believed in them despite every form of pressure to the contrary that human society can bring to bear, but here it’s the biggest and most persistent cynic who gains whatever favor the extraterrestrials have to bestow. But on the other hand, maybe I’m reading too much into Otto’s role in the final scene. Miller gets in on it too, after all, and nobody is more credulous than him.

Nevertheless, I’m sure I’m not just imagining things when I detect a kinship (if perhaps not an identity) between Otto’s outlook and Alex Cox’s. There’s simply too much material here that I can envision Otto himself devising if he were ever to try his hand at making a movie, too many small, snide details betokening an exquisite lack of faith in modern Western life as it was lived in the 80’s. Many of these are of minor importance, and indeed what significance they do have is apt to be missed altogether by viewers today. For example, people much under the age of 35 watching the movie now may not grasp that the featureless, white packages labeled “Corn Flakes,” “Beer,” or even just “Food” that can be seen stocking the shelves of all Repo Man’s retail establishments aren’t some kind of weird, sidelong comment on product placement in movies, but were rather meant to lampoon a real phenomenon: the inexplicable mania for generic groceries that swept over America for a few years during the first half of the decade, and then subsided just as suddenly as it arose. (No, seriously. It happened. I saw it; I was there.) Others, however, show Cox to be an exceptionally astute observer of oft-ignored undercurrents. Take a look at Otto’s parents, and you’ll see what I mean. They’re a couple of mentally neutralized ex-hippie wastoids, which is to say that they represent the other main recruitment pool for followers of shystey television salvation-pushers, largely overshadowed in popular culture by easily snookered retirees. Any close examination of what happened during the long comedown from the Summer of Love will reveal Evangelical Christianity as one of the means whereby those who turned on, tuned in, and dropped out during the late 60’s and early 70’s turned off, tuned out, and dropped back in a decade later, but only rarely is that acknowledged in fiction, whatever the medium. Consequently, it made me twice as happy as the wit in the writing itself could account for when Otto’s parents explained to him between tokes on the giant joint they were sharing that they just gave away all their surplus money to the Reverend Larry. A similar depth of perception is visible in the way Cox presents the punks with whom Otto associates before he joins up with Helping Hand. The satire there is surprisingly layered, as Cox seems to be poking fun simultaneously at both the punk scene itself and the anti-punk hysteria of the early 1980’s. Otto’s friends could have stepped right out of an episode of “Quincy” or “CHiPs,” except that they’re even more ludicrously caricatured. My favorite gag in that direction comes when Duke and Debbie grow bored with horning in on the dinner date at which Leila introduces Otto to the leader of her ring of would-be whistle-blowers. “You wanna go do those crimes now?” Debbie asks. “Yeah!” Duke replies, “Let’s go get sushi, and not pay!” At the same time, though, there’s a strange undertone of authenticity to the pair’s bumbling efforts to remake themselves as a Bonnie and Clyde for the leather-and-mohawks set, a misguided romanticism of outlawry that I’ve encountered from time to time in segments of the real-world punk scene where great surfeits of earnestness meet even greater shortfalls of perspicacity. To make jokes like these at the punks’ expense would seem to require not merely knowing them, but loving them on some level as well, so it comes as no surprise that punks themselves have tended to return Cox’s apparent affections.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact