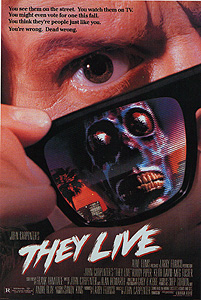

They Live (1988) ***½

They Live (1988) ***½

John Carpenter never struck me as much of a satirist. Admittedly, there are a bunch of his movies that I still haven’t seen (most significantly, Dark Star, In the Mouth of Madness, and Assault on Precinct 13), but my experience of Carpenter’s work is that cracking wise about the foibles of our species isn’t really his thing. That’s not to say that he can’t be witty (just look at Big Trouble in Little China), or that his movies don’t occasionally have big-ass subtexts that look too carefully delineated to be accidental (The Thing, anyone?), but he doesn’t make a habit of putting the two together, and one of his most conspicuous characteristics as a filmmaker is a very Hollywood tendency to approach his projects as pure entertainment. Rather old-fashioned of him, really, when you consider Carpenter in the context of his comparably well-known contemporaries, many of whom seem always to be commenting upon or reinterpreting something. There was, however, at least one time when John Carpenter unmistakably got his George Romero on. They Live, Carpenter’s final film of the 80’s, is a savagely snide piss-take on everything that was wrong with the decade— crass consumerism, mendacious politics, top-down class warfare, a hundred other varieties of power-elite chicanery, and above all else the craven complacency with which the Western (or at least Anglophone) middle class sold itself out by acquiescing to all of the above. Meanwhile, and less notoriously, They Live also satirizes itself and the genre of which it is a part, sometimes by flipping the clichés of 80’s action movies on their heads, and sometimes by playing hyper-inflated versions of them ludicrously straight. Occasionally that secondary mission gets in the way of the main one, but even so, They Live stands alongside RoboCop in the elite company of satires that have lost none of their timeliness even after a quarter of a century.

A drifter who is never named in the film proper, but whom the closing credits identify as “Nada” (former pro wrestler Rowdy Roddy Piper, whose acting career also encompassed Sci-Fighters and Hell Comes to Frogtown) strolls into Los Angeles some months after losing his livelihood and all that went with it in Denver. The construction industry is more vulnerable to economic fluctuations than most, and with the effects of the mid-80’s savings-and-loan crisis starting to be felt in a big way, nobody wants to build much of anything. LA is a much bigger and busier city than Denver, though, so Nada doesn’t have to spend too much time on unemployment before he finds a work site in need of a short-term hand. Nevertheless, some indication of the meager wages that job pays may be gleaned from the fact that Nada is far from the only homeless vagabond on the staff there. At the end of the shift, he is approached by another such man named Frank (Keith David, from The Thing and Pitch Black), who offers to take him to what amounts to a colony of transients organized and administered by a community activist called Gilbert (Peter Jason, of Dreamscape and The Amazing Captain Nemo). Nada is intensely suspicious at first— both of Frank’s motives and of Gilbert’s— and he detests the idea of accepting a handout with all the passion at the command of a white, working-class hard-ass who’s been indoctrinated his whole adult life to look down on welfare bums and charity cases. But like it or not, Nada is part of that underclass now, and he really hasn’t any better options, at least until he gets a few paydays under his belt. Besides, Gilbert and his people seem legit enough. At the very least, they’re not Moonies or Hare Krishnas.

Of course, Moonies and Hare Krishnas aren’t the only species of weirdo knocking around LA. Gilbert’s colony is set up in an undeveloped lot opposite a rundown African Methodist Episcopal church, and the minister there (Raymond St. Jacques, from Cotton Comes to Harlem and Voodoo Dawn) likes to come across the street to preach a strange gospel indeed. His words have the tone of a fire-and-brimstone sermon, but hit none of the expected points about sin or repentance. When he speaks of waking up to the presence of concealed evil in the world, it really doesn’t sound like he’s talking about Satan— or indeed about anything that fits in comfortably with the usual mystical Protestant apocalypse narrative. The minister intrigues Nada, and kind of gives him the creeps at the same time. Even more intriguingly creepy is Gilbert’s habit of going over to the mad preacher’s church late at night with several other men, and staying until just a few hours before dawn. And then there’s the guy on TV. A few of the inhabitants of Gilbert’s Hooverville have television sets, but lately the nighttime programming keeps getting sporadically interrupted by some beardy talking head whose ravings sound suspiciously similar in content (albeit drastically different in presentation) to those of the minister across the way. Something about mind control and hidden transmitters and a secret oligarchy of sinister puppet masters controlling the world from behind the scenes. One night, Nada’s mounting curiosity finally gets the better of him, and he sneaks into the church during one of its mysterious midnight services. The singing of the congregation proves to be merely a tape recording, and the building itself has been renovated inside to the point that it could no longer easily function as a place of worship. Instead, there’s a makeshift television studio— the source of the intrusive talking head broadcast— and some kind of packing and shipping warehouse filled with unmarked cardboard boxes. Nada is just beginning to think about cutting one of those open when a police riot squad descends upon both the church and Gilbert’s encampment. The cops roust the inhabitants with tear gas, bulldoze the hovels into the ground, and savagely beat anyone who comes within baton’s reach. That includes the preacher, who is getting the full Rodney King when last Nada sees him. Nada himself is one of the lucky few to escape with their skulls intact.

Well, if Nada wanted to know what was going on in the church before, just imagine how his curiosity must be gnawing at him now! The morning after the raid, he hooks work to revisit the scene. The police stripped the place pretty thoroughly, but to Nada’s great satisfaction, they missed one of the boxes from the hidden warehouse. Whatever he expected to find within, I’d say we can be reasonably sure it wasn’t half a gross of stylish sunglasses. Plausibly concluding that the glasses have to be a cover for some more normative form of contraband, Nada stashes the box in an alley with the aim of giving its contents a proper examination at his leisure. Then he sets out for a head-clearing walk, idly slipping on a pair of the enigmatic shades while he does so. The view through the sunglasses is unexpected to say the least. To begin with, the lenses filter out all the color from the light passing through them, so as to render the world in stark black and white. But more importantly, they reveal things that are invisible to the unaided eye. Every sign, billboard, and print medium on the street before Nada is now shown to conceal exhortations to “OBEY,” to “CONFORM,” to “MARRY AND REPRODUCE.” The money that changes hands at a corner newsstand proclaims, “THIS IS YOUR GOD.” Unearthly communications and surveillance devices sprout from every building, utility pole, and lamppost with a halfway decent sky arc. And some of the people around Nada aren’t exactly people. The glasses reveal about one in every fifteen of them to be horrid creatures with bulging, glassy eyes and translucent, corrupt-looking flesh. The distribution is less even than that sounds, though. Without the glasses, the monsters appear to be not just anyone, but people in positions of wealth, power, and authority. They’re the office professionals in expensive suits, the glamorous women bedecked in jewelry and furs, the cops with rank chevrons on their uniform sleeves. And once they realize that Nada can see them as they really are, they begin actively seeking his capture and destruction.

Mind you, Nada is perfectly happy to seek the converse right back. His counterattack starts small, when a skirmish with some cops culminates in him killing their inhuman leader, and helping himself to the dead creature’s sidearm and twelve-gauge riot gun. Then Nada notices while passing by a bank that literally everyone doing business within is a monster. Seeing that pushes his berserk button, and he barges in and begins shooting up the place. That wasn’t the smartest move Nada could have made. The next thing he knows, he’s a fugitive from the law, forced to compound his crimes by taking a random stranger (Meg Foster, from Masters of the Universe and Stepfather II) hostage to drive getaway for him, and trying to hide out at her house. Obviously he’s going to need allies, but his attempt to make one of his hostage doesn’t go very well. Frank, too, assumes that Nada has gone crazy when they meet up after the former gets off work that evening, but he changes his tune once Nada forces him to don a pair of the glasses from the church, and he sees for himself the creatures and their ubiquitous thought-control messages. Even so, two men against a conspiracy with all the power of the Los Angeles municipal authorities at its disposal (to take only the most conservative estimate consistent with the evidence so far) makes for pretty shitty odds. What Nada and Frank need to do is to find whatever’s left of Gilbert and the preacher’s underground resistance movement.

If you’ll permit me a moment up on Raymond St. Jacques’s street-corner soapbox here, it should piss you off that today, in 2012, the only things about They Live that feel truly dated are Meg Foster’s makeup and Rowdy Roddy Piper’s hair. If anything, the world’s power structures are more securely in the hands of a parasite aristocracy now than they were 24 years ago, and that aristocracy has gotten even better at manipulating the media to encourage complacency and collaborationism among the masses whose toil feathers the masters’ beds. They Live’s metaphor of alien mercantilists exploiting even the most advanced of Terrestrial societies like Third-World client states has only gained in relevance as the cult of the Free Market increasingly brings the First World down to the Third’s level. The same goes for the movie’s depiction of a formerly prosperous working class reduced to the status of serfs and helots, and kept in line by a police force that has grown hard to distinguish from an army of occupation. The only note rendered discordant by the passage of time is the text of one of the aliens’ subliminal commands, taken directly from the short story on which They Live was based; far from a formula for soul-deadening tedium, “WORK 8 HOURS, SLEEP 8 HOURS, PLAY 8 HOURS” sounds like a utopian pipe dream in an age when juggling two or three part-time jobs to make ends meet is the norm for a growing segment of the population. Supposedly there’s a remake of They Live under development, but that’s even more pointless than such things usually are. The police raid on the transient colony already suggests the rousting of an Occupy encampment, while the address by a representative of the aliens to a roomful of human Quisling capitalists could just as easily be a Koch Brothers fundraising dinner.

Now that I’ve got that out of my system, let me observe that the continued resonance of They Live’s satire says almost as much about what John Carpenter got right as it does about what the real world continues to get wrong. After all, had Carpenter not nailed this stuff in the 80’s, there’d be no reason to talk about how much of it still applies. Look, for example, at the way the aliens’ thought-control programming is paired with its carrier media. “MARRY AND REPRODUCE” is hidden within a billboard for a vacation package, featuring the image of a bikini-clad woman reclining on a beach. The sign for a newsstand commands, “STAY ASLEEP.” “CONFORM” and “OBEY” are all over the place, but invariably adorn the backdrop whenever an authority figure formally communicates with the public. The point is that these messages are already there as subtext— selling vacations with sex, packaging propaganda as news, psychologically buttressing the legitimacy of the political system by surrounding every junior city councilman who opens his yap before an audience with naïve patriotic iconography. Similarly insightful is the portrayal of how prolonged economic desperation affects the minds of even good people. By far the greatest strength of the aliens is that the folks with the most to gain from overthrowing them don’t want to get involved. Their prospects for basic survival are too tenuous for them to afford much in the way of principles. To know that the system is so thoroughly corrupted would force people like Nada and Frank to choose a side, so their sort warily avoid anything that might impart such knowledge. Even Nada, more curious than most, takes an immense amount of temptation before he commits to looking inside the church, and even then it’s plainly the unconscionable behavior of the police that convinces him that Gilbert and his associates are anything more than kooks.

Meanwhile, there’s a second layer of satire to They Live, which I didn’t pick up on when the movie was new. When I watched They Live for this review, not having done so in many years, I was rather taken aback to discover that this was Carpenter’s Weightlifter with a Machine Gun movie— his Raw Deal, his Commando, his Rambo: First Blood, Part II. That’s why Nada kicks off his initial one-man revolution with that gloriously nonsensical line about chewing bubblegum and kicking ass (which apparently started life as a bit of ringside shit-talk that Piper abandoned unused on the grounds that it was too corny even for the World Wrestling Federation). That’s why two guys who have most likely never handled a firearm in their lives magically acquire the ability to out-shoot whole armies of cops and alien security personnel. And from the opposite direction, it’s the explanation for the legendary fist-fight between Nada and Frank over Nada’s “mad” insistence that Frank try on the glasses, which drags on for nearly five and a half minutes with no sense of pacing and only the most rudimentary choreography, then leaves both participants bruised and limping for days afterward. Whereas most of They Live’s jokes at the expense of 80’s action movies are matters of exaggeration, that fight scene and its aftermath are an attempt to inject a form of realism that rarely dares show its face in the genre. It’s hard to say whether, on the balance, taking on two such disparate targets was a good idea. The shift in focus from anti-Reaganite social commentary to blowin’ shit up real good exacts a heavy cost in things like character integrity and thematic follow-through. But whether or not that shift was strictly worth it, I must admit that They Live’s third act is a pretty terrific send-up of some extremely deserving films.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact