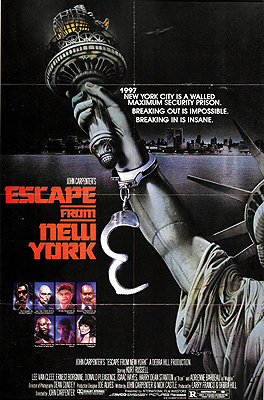

Escape from New York (1981) ***½

Escape from New York (1981) ***½

There’s a saying about science fiction which holds that it’s always really about the present, no matter how far in the future a given story might nominally be set. That’s because a fundamental technique of the genre is to extrapolate trend lines to the horizon and beyond: how would it be if things just kept getting more and more like the way they are now? What would the breaking point look like when it finally came? And what might arise from the rubble on the other side? John Carpenter’s Escape from New York wasn’t intended as a sequel to Assault on Precinct 13, but it might as well be one in the sense that the trend line it extrapolates was also the earlier film’s animating force, the strange succession of compounding crime waves that characterized the 20th century in America. And the restructuring that Escape from New York envisions following the crisis is the safest of all bets about human societies— that sufficiently prolonged chaos will produce a longing for the false and malicious certainty of authoritarianism. The specific manifestation of that longing which Carpenter and co-writer Nick Castle propose here, however, will win a rueful smile from anybody who lived through the transformation of New York City wrought during the mayoral administrations of David Dinkins and Rudi Giuliani.

1988: The American crime rate rises 400%. It isn’t clear whether we’re supposed to interpret that increase as occurring by 1988 or in 1988, but either way, the public has had quite enough of this shit, thank you. A new National Police Force is created, together with a new National Prison System, the two institutions combined wielding enough untrammeled power to make J. Edgar Hoover blow loads in his grave. In a gesture as symbolic of the national mood as it is practical, the National Prison System establishes its flagship facility in the most infamously lawless place in the country. The entire island of Manhattan is walled off to become one immense maximum-security prison, and all the bridges and tunnels leading into it seeded with explosive mines. The rivers encircling it are patrolled day and night by National Police helicopter gunships, whose crews are authorized to kill would-be escapees on sight. And with appropriately bleak irony, the headquarters from which all this is administered is located on Liberty Island, in the 19th-century star fort that serves as the base for the Statue of Liberty’s plinth. All Manhattan incarcerations are for life, although convicts sent there do have the option during their initial processing at Fort Wood to select termination and cremation instead. But for all that the island has become the ultimate symbol of the new, authoritarian America, life on the inside is even more anarchic than it was in the Bad Old Days, as the inmates are left alone to prey on each other to their hearts’ content.

1997: The United States of America is locked in a stalemated, years-long war against the Soviet Union and the People’s Republic of China, each of which may also be fighting the other at the same time. Surprisingly, the conflict has not gone nuclear except perhaps to the most limited extent, but the attendant privations and attrition have finally brought all three belligerents to the bargaining table. The President of the United States (Donald Pleasence, from American Rickshaw and Buried Alive) is scheduled to participate in the armistice negotiations personally, bearing a tape-recorded message having something to do with a breakthrough in the field of nuclear fusion power as a token of good faith and goodwill. It may already be too late for a negotiated peace on the home front, however, because a radical organization called the National Liberation Front of America have installed one of their agents (Nancy Stephens, of Halloween and Halloween H20) as a stewardess aboard Air Force One. She hijacks the plane, and after delivering a rambling address over the cockpit radio to whomever might be listening, pilots it to a death-dive into the side of one of New York’s abandoned skyscrapers.

The good news confronting National Police Commandant Robert Hauk (Lee Van Cleef, from It Conquered the World and The Octagon) is that Air Force One has a crash-resistant presidential escape pod, and all indications are that it performed as intended. The bad news, as Hauk learns when he leads an extraction team to the crash site, is that the president isn’t in that pod. Worse yet, an inmate called Romero (Frank Doubleday, of Dollman and Nomads) is waiting there to tell Hauk that the prisoners have taken the president captive, and will kill him unless their demands are met to the letter. Hauk will just have to wait a bit to learn what those demands are, however, because Romero hasn’t been entrusted with them. The Secretary of State (Charles Cyphers, from Assault on Precinct 13 and Dead Calling) wants to send in the army with guns blazing once word gets back to Washington, but any cretin can see that they’ll be bringing the president home in a body bag if that happens. Hauk senses an opportunity, though, in a prisoner who just arrived at Liberty Island Security Control that day for processing into Manhattan, and he has his right-hand man, Rehme (Tom Atkins, of Halloween III: Season of the Witch and My Bloody Valentine), see to it that said prisoner is diverted to his office before boarding the prison ferry.

Enter “Snake” Plissken (Kurt Russell, from Search for the Gods and The Thing). A twice-decorated hero on the Russian front of the current war, he was the finest soldier in an elite unit before something soured him on the military, the government, and society as a whole. Plissken went rogue, using his special forces training to facilitate a series of high-risk/high-profit robberies of banks, business payrolls, and similar institutional targets. Although the nature of his crimes might be taken to imply a political motive, it’s difficult to discern in Snake any ideology more specific than “fuck all y’all.” Be that as it may, the important thing is that the situation in Manhattan right now bears a marked resemblance to the circumstances under which Plissken earned one of his medals in Leningrad. Hauk therefore offers Plissken a deal: bring the president out of Manhattan alive within 24 hours, and go free with a full pardon. One doesn’t become Commandant of the National Police by being a sucker, though, and soon after Hauk secures Snake’s grudging cooperation, he reveals the fine print to their bargain. That broad-spectrum immunization against all the who-knows-what that’s surely endemic among the prisoners in the Big Apple that Snake just got as part of his mission prep? It also injected a pair of microscopic detonators into his bloodstream, designed to lodge themselves in the walls of his carotid arteries. They’ll go off automatically in 24 hours unless Hauk’s staff doctor neutralizes them— and since they can’t be neutralized at all until the final fifteen minutes of the countdown, Snake might as well go do what he agreed to first, don’t you think?

In theory, Plissken’s mission should be a simple one, although simple in this case is obviously a very different thing from easy. The president was wearing a vital sign transmitter bracelet when he ejected, enabling Snake to track his movements around the prison-city with a small, handheld device. Unfortunately, Plissken discovers very quickly that the president’s kidnappers anticipated such a ploy. When he tracks the bracelet’s signal to its source, he finds the gizmo not on the president’s wrist, but on that of an insane wino, to whom it was given precisely in the hope of throwing any would-be rescuers off the scent. Snake’s luck improves, though, when he falls in with a somewhat less crazy taxi driver (Ernest Borgnine, from Gattaca and The Black Hole), who seems to know everything that goes down on the entire island. Cabbie knows, for example, that the president is being held by the Duke of New York (Isaac Hayes, of Truck Turner and Uncle Sam), the prison-city’s de facto ruler, and that the Duke has big plans for him. He also knows where Snake can find the architect of those plans, Harold “Brain” Hellman (Harry Dean Stanton, from The Green Mile and Christine)— who just happens to be an old friend of Plissken’s, although it would be putting it mildly indeed to call their present relationship strained. Neither Brain nor his ex-prostitute consort, Maggie (Adrienne Barbeau, of Someone’s Watching Me and The Fog), will be happy to see Snake, but since he comes to them in a credible position to spread presidential pardons around, they might be inclined to help him out anyway.

I never lived in New York, but it was a frequent weekend destination for me and my family from the mid-1990’s through the early aughts. Usually we went up there because some band we knew personally had scored a gig at CBGB or the Continental Club (although there was one time when my parents wanted a particular piece of discontinued Ikea furniture, and the closest branch that still had it in stock was in Elizabeth, New Jersey), which meant that we’d spend most of our time in parts of the city that white suburbanites like us were supposed to be afraid of. From our intermittent vantage point at the St. Mark’s Hotel (a longtime flophouse for misfits at the corner of St. Mark’s Place and 3rd Avenue, which still rented rooms both by the hour and by the week when we first started staying there), we got to watch the last vestiges of the real New York that inspired John Carpenter’s fictional one wither up and blow away, until a truer caricature of Manhattan was that the entire island had become a gated community for the rich. But in fact that transformation was driven by the same political tailwinds that led Carpenter to imagine the prison-city of Escape from New York. It’s merely that the trend lines in reality weren’t allowed to reach the horizon, as they almost never are. The breaking point had already come by 1981, and a much more limited reaction sufficed to turn things around. The irony, of course, is that no one who didn’t frequent New York during its open-air madhouse years seems to have noticed the change. Old Dirty New York may be gone from this world apart from a few lingering pockets in the Outer Boroughs, but it lives forever in the fevered imaginations of those who have never come nearer to the East Village, the Bowery, or Alphabet City than the Villages.

In Assault on Precinct 13, there was a certain ambivalence on display for those who cared to look for it. The hero of the film was a police officer, but there was nothing heroic at all about the organization to which he belonged. His chief ally was a charismatic murderer who kept his own counsel about what drove him to his crime, but whom anyone save presumably his victims could absolutely trust to have their backs in an emergency. Another major character was an innocent victim, transformed by victimization into a savage beast, and then broken in mind and spirit by the recognition of his unsuspected capacity for bloodlust. Even the unambiguous villains, to the small extent that their motives can be inferred, may not have been totally unjustified in their opposition to the forces of law and order, however monstrous their actions in service to that opposition. But that was 1976, when the social and political conversation about burgeoning crime rates was still at the “We have to do something about this!” stage. In 1981, it was obvious that “something” was going to mean stop-and-frisk, “broken window” policing, and the ever-broader application of Daryl Gates’s SWAT model of paramilitarized law enforcement. It was going to mean mass incarceration, for-profit civil forfeiture, and coerced plea bargains in lieu of trials for the vast majority of criminal suspects. Perhaps most dangerously of all, it was going to mean the valorization of vigilantism across virtually the entire political spectrum, and the open repudiation of the very concept of rights for the accused. Consequently, there’s no ambivalence at all in Escape from New York. This time, the hero is the outlaw of outlaws, his allies are all condemned criminals, and there’s very little to choose between the tyranny of crudely sadistic violence represented by the Duke of New York and the more orderly, institutionalized tyranny represented by Commandant Hauk. The key scene for the entire film comes just before the end, when Plissken gets a moment to ask the president what he has to say about the people who died getting him out of Manhattan. The president pauses for a second, visibly nonplussed, before fumbling out, “Well, I thank them, of course. America thanks them.” In that moment, it’s obvious that he doesn’t even understand the question. The highest authority in the land is unable to perceive the humanity— the reality— of Plissken, of the people incarcerated in Manhattan, of the doomed passengers and crew of Air Force One, and no doubt of any of his constituents, save perhaps a few among the most exalted ranks of the wealthy and well connected. This scene has not lost one scintilla of its relevancy at any point during the intervening 43 years.

It’s always instructive to revisit a well-made, whip-smart movie that inspired a host of lousy, dumb ones, not least because the difference can arise in surprising ways. Like, obviously Escape from New York would owe a large part of its superiority over After the Fall of New York and 1990: The Bronx Warriors to the most iconic of Kurt Russell’s four career-redefining performances for John Carpenter, and to Donald Pleasence’s subtly powerful portrayal of a weak little man who is in no way worth the sacrifices that so many people end up making on his behalf. Obviously the guy who made Dark Star could populate a dystopian future New York with a whole menagerie of memorable loons and weirdoes. Of course the director of Assault on Precinct 13 and Halloween could juggle action and suspense to potent effect. But Escape from New York is also one of those rare films in which even the loosest ends yield unexpected creative inspiration when you tug on them a little. I’ll let the single example of Cabbie make the case for me. At one point, he mentions that he’s been driving the same taxi for 30 years— and from the state of his beat-up old Checker Marathon, I believe it! But remember that Manhattan didn’t become America’s highest-security prison until sometime after 1988, a mere nine years in the past from the vantage point of the movie’s main action. Now we could just crow, “PLOT HOLE!” and pat ourselves on the back for our perspicacity, but what if we try to take this line at face value? Might it mean that only some people were allowed to evacuate Manhattan when it was converted into a prison? Or maybe that there were longtime residents so ornery that they refused to be removed from their homes, even at the cost of having to spend the rest of their lives walled in with thousands of the country’s worst criminals? Hell, what if Cabbie did leave in 1988, but ended up missing the old neighborhood so badly that he did something appalling in order to be sent back to it? We can make as much or as little of this is we want, but that’s my point. Any one of those possibilities would be consistent with the movie’s broader themes, and any one of them would make the tapestry of Escape from New York’s imagined world richer. There are vistas formed by Carpenter and Castle’s lightest offhand sketching here, and even if they consist almost entirely of things the viewer imputes to them, the mere fact that such imputing is possible in the first place elevates this movie above its multitudes of shallower, clumsier imitators.

My only really serious complaint with Escape from New York is that it remains too narrowly focused throughout on Snake’s travails while searching the prison-city for the president. There’s little cohesion to the threats that Plissken faces, and although that’s understandable in a place where every tenement is home to its own picturesque malefactor, it does somewhat limit the movie’s capacity for steady escalation. What Escape from New York really needed was more of the Duke of New York. Carpenter should have introduced him earlier, through the president’s eyes rather than Plissken’s, and given Isaac Hayes more opportunity to cut loose in the part. I suppose one could argue that Carpenter had already used shifting perspectives to generate suspense in both Assault on Precinct 13 and Halloween, and that his approach here is therefore preferable to repeating himself, but there’s also much to be said for just doing what works. It’s indicative, I think, of what this movie misses out on by keeping the Duke offscreen for the most part that I’m forever misremembering Cyrus’s address to the assembled gangs of New York in The Warriors as a scene from Escape from New York instead.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact