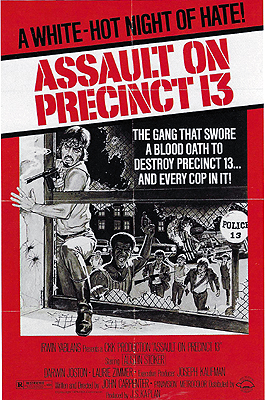

Assault on Precinct 13 (1976) ****

Assault on Precinct 13 (1976) ****

John Carpenter always struck me as an odd filmmaker to have written and directed a crime-panic movie, even granting that Assault on Precinct 13 came early enough in his career that he was probably still figuring himself out at the time. I mean, we’re talking about the guy who would later make Escape from New York and They Live, and who now unapologetically devotes his retirement from showbiz to smoking weed, playing video games, and recording weird music with his son. Copaganda hardly seems like his speed, you know? But it turns out that Assault on Precinct 13 is not at all the film that a straightforward statement of its premise would seem to imply. Yes, it’s about an army of criminals laying siege to an understaffed police station. Yes, it nevertheless owes a great deal to Night of the Living Dead, not just structurally and tonally, but in its portrayal of the attacking youth gang as something mysterious, inscrutable, and so far beyond the understanding of experienced law-enforcement personnel that one of the latter can wonder half-seriously whether unusual sunspot activity is to blame for their behavior. And yes, it draws just as heavily upon the Hollywood Westerns of the 1950’s (especially Fort Apache and Rio Bravo), which might be expected to inject their own set of unfortunate implications. But the closer you look at Assault on Precinct 13, the more it confounds the natural assumption that it’s Carpenter’s out-of-character answer to Dirty Harry or Death Wish.

Indeed, this movie begins with such a confoundment, setting the stage for all the others to follow. At 3:10 AM on one angry-hot summer Saturday, in the blighted but apparently fictional Los Angeles neighborhood of Anderson, half a dozen members of the youth gang Street Thunder walk into an ambush. Obviously these guys are up to no good (nobody goes out at three in the morning packing that much heat unless they’re planning something profoundly antisocial), but the cops who draw down on them from the overlooking rooftops don’t even give them a chance to comply with the order to drop their weapons before raking the alley where they’ve been caught with shotgun fire. As soon as word of the massacre gets out, the gang’s four leaders (Al Nakauchi, James Johnson, Gilbert de la Pena, and Frank Doubleday— the latter of whom was also in Escape from New York and Abar) perform a blood ritual at Street Thunder headquarters, dedicating themselves to avenge their fallen comrades, or die trying.

Flash forward to the following afternoon. At 4:50 PM, the LAPD’s newest lieutenant, Ethan Bishop (Austin Stoker, of Abby and Time Walker), sets out for his first night on the job. Calling in on his cruiser’s radio for the evening’s assignment, Bishop is taken aback by the order to proceed to Precinct 9, Division 13— the old Anderson station, which is being shut down in favor of a new facility at 1977 Ellendale Place— to preside over its final decommissioning. When Bishop arrives at his destination most of an hour later, he finds Gordon the precinct captain (James Jeter, from Diary of a Teenage Hitchhiker and Death Scream) decidedly squirrelly, as if he were expecting something bad to happen, and wanted to make sure he was securely settled into his new digs before it went down.

Meanwhile, in Las Cruces, Special Officer Starker (Charles Cyphers, from Someone’s Watching Me and Halloween Kills) arrives at the county jail at 5:11 PM to collect three inmates for transfer to their long-term home at the state penitentiary in Sonora. Two of the men— Wells (Tony Burton, of The Black Godfather and CyberTracker 2) and Caudell (Peter Frankland, from Puppet Master and Saturday the 14th Strikes Back)— are just workaday cons, but Napoleon Wilson (Darwin Joston, of Rattlers and Eraserhead) is a veritable celebrity of crime. We never will learn just what he did or why; suffice it to say that Wilson is a multiple murderer, and that the circumstances were shocking enough win him a nominal death sentence. (The Supreme Court ruled capital punishment as generally practiced in the United States unconstitutional in 1972, and only three states had revised their statutes for death sentences sufficiently to pass muster by 1976. California in those days treated death row as something like the criminal equivalent of Dean Wormer’s “double secret probation”— an impressive-sounding but functionally meaningless upgrade from life in prison) Nevertheless, Starker is drawn to Wilson as an enigma. The man just doesn’t act like a killer, and the officer hopes to spend the long bus ride upstate figuring him out. Unfortunately, Caudell happens to be sick, and although the warden at the jail dismisses his illness as a mere cold, his condition worsens rapidly. By the time the bus reaches Los Angeles, it’s obvious that the man needs a doctor— and chances are that everyone else aboard will be needing one, too, before their intended final stop in Sonora. A quick look at the map reveals that the nearest place to pause with the necessary lockup facilities is Precinct 9, Division 13, in Anderson.

Finally, at 5:37, an affluent beach-and-canyon type named Lawson (Hellhole’s Martin West) drives into Anderson with his little daughter, Kathy (Kim Richards, from Devil Dog: The Hound of Hell and The Car), on a mission to persuade the girl’s newly widowed nanny to flee the rapidly degenerating ghetto and move in with them. Unsurprisingly, Lawson doesn’t know his way around the area, and he gets so thoroughly lost that he’s still driving haplessly in circles more than an hour later. At 6:41, he gets sufficiently exasperated to pull over at a pay phone and call for directions, giving Kathy a dollar for an ice cream cone while he talks to the nanny. That’s how the child becomes a collateral casualty when the leaders of Street Thunder fatally mug the ice cream vendor to get their bloodlust up for the night’s coming retaliation against the police. Lawson doesn’t quite witness his daughter’s unprovoked murder, but he arrives on the scene quickly enough to see the gang-bangers driving away. Helping himself to the pistol under the dashboard of the ice cream van (Carpenter understands the central fallacy of relying on guns for self-defense: by the time you know you’re in a shooting situation, it’s generally too late to draw), the grief-maddened father speeds off in pursuit. It takes him until after nightfall to catch up, but the initial shootout between him and the Street Thunder chiefs goes all his way. Indeed, although Lawson has no way of knowing this for certain, the man he kills is the specific one who gunned down Kathy. The three surviving criminals quickly regroup, however, and Lawson is all out of borrowed bullets by then. Fortunately, the confrontation happens close enough to a police station for Lawson to reach it on foot before his enemies catch him. Considerably less fortunately, the station in question is (you guessed it) Precinct 9, Division 13.

Put it all together, and Lieutenant Bishop has a great deal more on his hands than the demeaningly simple babysitting job he was led to expect that afternoon. Lawson arrives mere moments after Starker’s bus, and Street Thunder descends in full force not long after that. The gangsters’ opening attack kills Starker, Caudell, Desk Sergeant Chaney (Henry Brandon, from Captain Sindbad and The Land Unknown), and all the correctional officers who rode in from Las Cruces, leaving Bishop alone to defend the precinct apart from Captain Gordon’s secretary, Leigh (Laurie Zimmer), and Julie the switchboard operator (Nancy Loomis, of Halloween and The Fog). Lawson, for all his earlier savagery, is now practically catatonic, so if Bishop and the women would like to survive the night of ever-escalating siege, there’ll be nothing else for it but to release Wilson and Wells from their holding cells, enlisting them in the hopelessly uneven battle against Street Thunder.

Crime rates in general, and rates of youth crime in particular, really did climb steadily for most of the 20th century before leveling off and reversing course in the mid-1990’s. There’s no obvious single reason why, and none of the proposed explanations seem adequate to account for all aspects of the phenomenon. By the 1970’s, the problem was so acute, and the mysteries surrounding it so intractable, that it became fashionable to view young criminals almost as belonging to their own species, driven by alien motivations and unresponsive to any incentive structure that their “normal” elders could devise. Assault on Precinct 13 acknowledges that perspective, but stops significantly short of endorsing it. And although it never puts forward any explicit alternative theory, either, Carpenter sprinkles the film with clues to several, above and beyond Ethan Bishop’s off-the-cuff suggestion that maybe it’s sunspots making everyone crazy.

The first thing worth noting is that the altercation between Lawson and the leaders of Street Thunder is only the proximate cause of the titular assault. It’s obvious from the first several scenes (especially if we factor in various tidbits of intel from overheard radio news broadcasts) that the gang and the police department have been waging war on each other for some considerable while. There are also intriguing hints of a link between Street Thunder and the youth radicalism of the lately concluded Vietnam era. The gang’s strategy and tactics suggest deliberate paramilitary training and a conscious attempt to adapt the principles of guerilla warfare and terrorist insurgency to the environment of an American urban ghetto. The newscaster remarks not only on the gang’s relatively recent emergence, but also on the unusual racial and ethnic diversity of their membership, suggesting the coalescence of several established mobs around a core group of new leaders experienced in the various leftist minority nationalisms inspired by the Black Power movement. Tellingly, the Warlords (as the closing credits dub Street Thunder’s four chieftains) look rather like Che Guevara, Huey Newton, Yasser Arafat, and Sonny Barger have joined forces to create conservative America’s worst nightmare. And perhaps even more tellingly in that context, it’s the white Warlord who murders Kathy and the ice cream man for no real reason, as if in his specific case, the political concerns implicit in his fellows’ appearances really are secondary to the drive to sow violence and chaos.

At the same time, though, there’s plenty of reason to suppose that the cops aren’t exactly the good guys here, either, Ethan Bishop notwithstanding. The opening alley ambush, after all, has more in common with a mob hit than with any legitimate law-enforcement operation. Also, Captain Gordon seems to realize that he’s hanging Bishop— both the new guy on the force and black— out to dry when he hands Division 13 over to him, and seems not to be even the tiniest bit troubled by that. And as if that weren’t enough, even Lawson is plainly mistrustful of the police in Anderson, pointedly passing up an opportunity to ask them for assistance during his doomed search for the nanny’s house. Gordon’s men must be bad news indeed if a guy like that wants nothing to do with them!

Then there’s Napoleon Wilson. Whatever else he may be, Wilson is no juvenile delinquent, student radical, or teenaged super-predator. Yet the central fact of his characterization is that no one can figure out why he did whatever heinous thing it was that’s sending him to Sonora for the rest of his life. The kids, that is to say, have no monopoly on seemingly inexplicable criminal violence. Furthermore, because Carpenter never so much as implies the possibility that Wilson was wrongly convicted, his conduct under fire at Division 13 (and Wells’s, too, for that matter) paradoxically insists that even the worst offender is capable of courage, honor, and loyalty under the right circumstances.

All that makes Assault on Precinct 13 a surprisingly challenging film, but it’s also nearly subliminal. What’s right out in the open is a taut and gripping action/suspense thriller that feels almost as unexpected coming from John Carpenter as Elvis or Starman. Fittingly, given that Carpenter was consciously striving to channel the likes of Howard Hawks and Don Siegel, this movie displays exactly their breed of unostentatious technical mastery. While there’s no DIRECTING! or CINEMATOGRAPHY! to be seen here, neither is there any shortage of clear, carefully thought-out imagery; deft modulations of tone; or subtly meaningful juxtapositions of scene against scene, setting against setting, line against line. The whole movie is one enormous elaboration of the bomb-under-the-table principle, as the three different first-act plot threads converge inexorably toward the explosion of retribution promised by the gang leaders in the second scene, and each successive wave of Street Thunder’s attack leaves the police station’s defenders in a slightly worse position. Carpenter serves up some good Hawksian banter in his capacity as screenwriter, too, predicated upon Napoleon Wilson’s recognition that things really can’t get much worse for him than they already were, no matter how the night’s battle shakes out. All in all, while Assault on Precinct 13 might seem on the surface like a minor early work, it’s almost as important as Halloween in setting the terms for Carpenter’s subsequent development as a filmmaker.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact