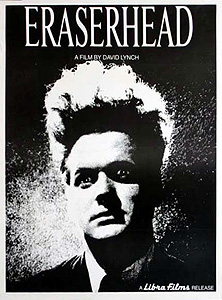

Eraserhead (1977) *****

Eraserhead (1977) *****

As with most forms of art, or so I would imagine, there are some movies that simply cannot be understood without a certain amount— or, more to the point, a certain kind— of life experience to guide you. Unless you have seen or felt or been otherwise exposed to something analogous to whatever inspired their creators, you just aren’t going to get it. With that in mind, I offer the following as my blessing to you all: may you never be able to grasp how Eraserhead makes any kind of sense whatsoever.

I was a teenager the first time I saw Eraserhead, and at that point in my life, I could interpret it only as a loosely structured parade of disquieting imagery and bizarre situations. If there was a story being told, it was beyond me to guess what it might have been, and all I took away from that first viewing was an awareness that I had just seen something almost indescribably weird, and that I now felt kind of bad for reasons I couldn’t quite put my finger on. That seems to be how most people initially respond to Eraserhead, and if we may judge from the combination of shoulder-shrugging and facile Freudianism that comprises so much of the commentary on it over the years, then it would seem that many— even among those who make their living from watching and thinking about movies— never get too far beyond that level. This last time around, however, I realized with considerable alarm that Eraserhead seemed to be making, if not perfect sense, precisely, then certainly a great deal more sense than I wanted it to. May the gods help me, I actually found myself relating to it! Thus it is that I wish everyone continued incomprehension, for what this singularly distressing mindfuck of a movie most seems to be about is the horror of a misfit personality facing the dreadful realization that his life is never, ever, ever going to be what he wanted it to.

Writer/director David Lynch claims that in 30 years, he has yet to read an interpretation of Eraserhead’s deliberately obscured and distorted plot that quite matched what he had in mind, and I doubt that mine is going to be the first. Nevertheless, this is what I saw: Henry Spencer (Jack Nance, later of Dune and Ghoulies) loses his job at the print shop— although he prefers to think of it as being “on vacation”— and trudges home through some desolate Rust Belt hellscape of a city to his shabby little apartment. On his way in, he is stopped by a neighbor, the menacingly beautiful woman (Judith Anne Roberts) who lives across the hall from him in unit 27, who informs him that someone named Mary called on the pay phone in the lobby to invite him to come have dinner at her house tonight. Henry doesn’t know quite what to make of this development, for Mary (Charlotte Stewart, from Tremors and Dark Angel: The Ascent) is his ex-girlfriend, and he hasn’t seen her for a number of months. There was no break-up per se; Mary just dropped out of his life one day without any explanation, and yet here she is inviting him over for dinner like nothing out of the ordinary has happened between them.

Mary and her family live in a rather dumpy little house in a different part of the city. When Henry arrives, his making-up conversation with his ex out on the front porch is a little strained, but seems more or less a success. He comes inside and meets the girl’s parents (Jeanne Bates, from The Soul of a Monster and Back from the Dead, and Allen Joseph, of Saturday the 14th and The Return of Count Yorga), a scene which also feels strained but essentially successful. Dinner is a disaster, however, and worse still comes immediately thereafter. It turns out the reason Mary vanished from sight is that Henry got her pregnant. The baby was born prematurely a few days ago, and is waiting to be claimed at the hospital. Mary’s mother, meanwhile, expects Henry to do the right thing and marry her daughter.

Henry and Mary’s existence as husband and wife is an unmitigated catastrophe. Henry never does get a new job, the severely defective baby overwhelms both Mary’s maternal competence and her maternal compassion, and before long, the couple have split up, with Mary leaving the infant in Henry’s equally inept care. Henry has a brief affair with the woman in apartment 27, but their relationship is scuttled before it can get properly underway when the neighbor decides that she is absolutely not prepared to deal with Henry’s child. Henry recognizes as much when he catches her out in the hall with another man, and recognizes further that that is how things are always going to be for him from now on. He stabs the baby to death with a pair of scissors, then electrocutes himself with one of the apartment’s light fixtures.

It’s a sufficiently depressing story all by itself, but the imagery in which that story comes cloaked is what makes Eraserhead such harrowing viewing, even if you can’t make heads or tails of what’s going on. Dream and fantasy sequences full of mystifying psychological symbolism interpose themselves into the action with little warning, and even the “real world” parts of the film feature so much weird behavior, nonsensical dialogue, and what I can describe only as random breakdowns in reality that they feel every bit as nightmarish as the genuine nightmares. Some examples: No sooner has Mary’s mother dropped her baby bombshell, and warned Henry that he’s going to be in serious trouble if he doesn’t cooperate, than she seizes him by the shoulders and begins aggressively making out with him. Rather than tossing the salad for dinner in the usual way, Mom instead places the salad spoons in the hands of Mary’s catatonic grandmother (Jean Lange), and wields her limp arms like a marionette’s. Immediately after launching off on a mini-rant about the world’s lack of appreciation for plumbers, Mary’s father aggrievedly demands that Henry look at his knees, as if the logical connection between the two (and there’s nothing noticeably wrong with the man’s knees, by the way) were perfectly obvious. When Henry goes to carve one of the freakishly tiny chickens he and Mary’s family are supposed to be eating (“Strangest damn things,” says her father, “They’re man-made.”), the roasted bird comes suddenly to life, twitching spasmodically and spraying great gouts of blood from its empty abdominal cavity. That’s the sort of thing that passes for “normal” in Eraserhead.

I think that’s part of the reason why so many people describe this movie as taking place in a post-apocalyptic future; the rest has mainly to do with the look of the film, which is bleaker and grittier than just about anything, oppressively dominated by vistas of entropic collapse. However, there is nothing at all (except possibly that one line about man-made chickens) in either the action or the dialogue that particularly indicates such a setting. Instead, I believe everything we see outside of Henry’s dreams and fantasies looks, sounds, and feels the way it does as an attempt to convey to the audience the subjective experience of being Henry. Remember what I said Eraserhead seems to be about, and consider that there is much basis in David Lynch’s contemporary life circumstances to support such a reading. Lynch spent the five years that it took him to complete Eraserhead living in Philadelphia, a city he hated, and that was, in the 1970’s, sinking rapidly into post-industrial decay. It would have been a depressing place to live, even if you liked it there. Meanwhile, he found himself— much like Henry— accidentally saddled with a family he didn’t want. Parenthood is something that changes your life irrevocably. For those who want to be parents, I’m sure attaining it must be the most fulfilling experience imaginable; for those who don’t, I’m equally sure it must look like all the lights of the future winking out in cascades, like a metropolitan skyline in the grip of a blackout. And while I can’t speak specifically for unwilling fathers, I have seen a few cherished futures evaporate irretrievably before my eyes for other reasons, and I can assure you that the world really does look like Eraserhead when it happens to you. Everything you see is ugly; everything you hear is uncomfortably, insistently loud; nothing happening around you makes any sense; all of existence seems vaguely, impersonally hostile. The genius of Eraserhead lies to a great extent in its ability to impart to its viewers the shapeless horror of that state of mind, even if they have no experiential basis upon which to recognize it for what it is.

The rest of its genius lies in its power to convey the very concrete horror that Lynch felt in the face of fatherhood, even to people who cannot conceive of feeling such a thing. This, I think, is what really gets people walking out of the theater and leaping up to push “eject” on their VCRs and DVD players. While synopsizing Eraserhead, I described Henry and Mary’s baby as “defective.” That was putting it mildly. When her mother passes on the news after dinner, Mary protests, “Mother, they’re still not sure it is a baby!” Not that they aren’t sure it’s Henry’s baby, mind you— they aren’t sure it’s a baby in the first place. You can see why not. The proportions of its head look more like an animal’s than a human’s, it has no limbs of any kind, and when Henry unwraps its swaddling prior to killing it, we see that it has no proper body, either— just a mass of loose internal organs, partially contained by a gaping ribcage. From the very beginning, David Lynch has refused to reveal how the puppet representing the infant was made, but among the more popular hypotheses is that it was somehow constructed out of a fetal lamb or calf. The simple fact that the prop’s fundamental appearance remains unchanged throughout a film that was shot over the course of five years argues strongly against that idea; surely no single livestock fetus could have been successfully preserved for that long. Nevertheless, that’s certainly what the baby most resembles. And when the child suddenly comes down with a mysterious sickness one night, it looks for all the world like the puppet really is rotting away. Even before factoring in its almost literally incessant mewling cries, it is impossible to greet Henry’s baby with anything more favorable than pure visceral revulsion, and yet that noisome puppet is appallingly convincing as a living child. That’s what makes the concluding infanticide scene so disturbing. The baby seems terribly real, terribly alive, and its father is stabbing it in the heart with a pair of scissors, yet I can virtually guarantee that a part of you will be sighing, “Oh, thank God!” when it finally happens. Nobody wants to root for infanticide, but Eraserhead leaves you no choice in the matter. Lynch succeeds in forcing the audience to experience his darkest and most evil escape fantasy, together with the sick self-loathing that must inevitably accompany it in any person of conscience. It’s an awful sensation, and no one who finds Eraserhead too much to take because of it has anything to be ashamed of, even if they can’t quite trace what’s making them feel that way.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact