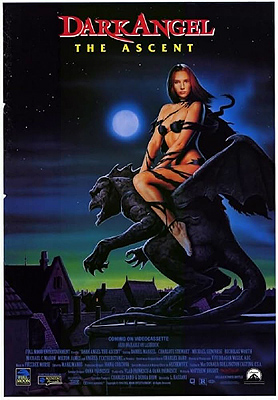

Dark Angel: The Ascent / The Dark Angel (1994) ***

Dark Angel: The Ascent / The Dark Angel (1994) ***

I’ve touched on this before in other reviews, but it bears repeating once again: Hell as depicted in most of Western culture today is almost entirely extra-Biblical. That’s especially true, too, of how we tend to imagine the role of Satan, and of devils generally, within it. The concept of Hell as a domain of devils, with Satan as its supreme overlord, owes more to Dante Alighieri, John Milton, and the anonymous authors of a hundred forgotten Medieval passion plays than to any ancient prophet, priest, or apostle. What’s more, modern pop culture has garbled and misconstrued even those sources into utter theological nonsense in the process of mixing and matching. When the Gospel According to Matthew speaks of sinners being banished into the eternal fire prepared for the Devil and his angels, the idea is that we’re going to share those beings’ fate, not that we’ll be remanded into their custody. And although Dante portrayed the lesser devils basically having the run of the Inferno, he did so in much the same way as No Escape shows Marek and his gang running the Absalom prison island: there’s no punishment more fitting for those assholes than to be left permanently at each other’s mercies. Once you bring in Milton, though, with his dignified, regal Satan, you’ve got a real conceptual problem, because Milton’s Lucifer was written with an eye toward the Devil’s supposed capacity as the ruler of this world, granted a temporary lease to the Earth by God (for Reasons), but doomed in the long run to defeat and overthrow. Put Milton’s Satan in charge of Dante’s Hell, and you give him an indispensable, eternal role in the administration of Divine justice, so that his “rebellion” becomes in fact a necessary part of the enterprise of creation. Unless you’re a complete monster (or a Calvinist— but I repeat myself), it no longer makes any sense at that point for God to be punishing Lucifer at all, or for us to understand the two entities as mutual foes.

I realize that this is an improbably weighty note on which to begin a review of a direct-to-video horror movie from the mid-1990’s, let alone one made under the imprimatur of Charles Band. But what makes Dark Angel: The Ascent so extraordinary is that its entire storyline proceeds from an attempt to build a coherent (if unapologetically heretical) moral cosmology around the disjoint intersection between formal Christian theology and the implications of pop-culture Hell. To continue the discussion of Band’s self-appointed successorship to Roger Corman begun in my review of Arcade last year, Dark Angel: The Ascent is one of the rare films that show Band in New World Pictures mode, as opposed to AIP mode or Filmgroup mode. Much as Corman did with projects like The Student Nurses and The Velvet Vampire, Band left writer Matthew Bright and director Linda Hassani free to be as arty and strange as they wanted in Dark Angel: The Ascent, just so long as the finished product featured enough gore and nudity to be credibly sold as an exploitation flick to the core Full Moon Entertainment customer base.

Veronica Maria Theresa Valeria Iscariot (Angela Featherstone, of Soul Survivors and Caved In) is too young to have participated in Lucifer’s rebellion. Indeed, given the genealogy she’ll have occasion to recite later, I suspect that even her parents, Hellikin (Nicholas Worth, from Hell Comes to Frogtown and Swamp Thing) and Theresa (Charlotte Stewart, of The Girl with Hungry Eyes and Eraserhead), are native denizens of the Inferno, with no firsthand experience of any other plane of existence. Veronica has dreams, though— dreams of a world not enclosed by dungeons, caverns, or pits, lit by a blazing golden orb set in an impossibly distant dome of radiant blue, the heat of which is shockingly gentle in contrast to the cruel fires of Hell. Her teachers at torture school take a very dim view of her discussing these dreams, however, and her father reacts to them the way Archie Bunker would have reacted to his daughter marrying not merely a liberal, but a Black Panther. Even Veronica’s best friend, Mary (Cristina Stoica, from Lurking Fear and Lurid Tales: The Castle Queen), finds the intensity of her fixation on these dreams a little disturbing, although she doesn’t share their elders’ appalled terror in the face of them. In fact, Mary feels only the slightest twinge of misgiving about taking Veronica to see a cavern she learned about recently, which reputedly goes all the way up to the fabled surface world of humankind. Both devil-girls are reasonably sure that’s what Veronica has been dreaming about, but Mary, content with the lot of the Fallen, has no desire to see the place. That night, though, after an explosive fight with her father at the dinner table, Veronica takes her pet hellhound, Hellraiser, and runs away from home— straight up Mary’s rumor-laden cavern.

She ultimately emerges through a manhole into a city in what Linda Hassani just barely asks us to accept as anyplace other than post-communist Romania (where most of the more ambitious Full Moon movies were being shot in those days). By some miracle mysterious even to her, Veronica’s wings, tail, talons, horns, and pointed ears all vanish the moment she sets foot on mortal soil, but the transformation into an apparently human woman does not extend to conjuring up setting-appropriate clothing for her to wear. Nude redheads being nearly as conspicuous on busy streets as devil-girls, Veronica flees from the crowds, following Hellraiser’s unerringly helpful nose to a bundle of old but serviceable clothes discarded in a nearby alley. Evidently devils have no experience of motor vehicles, however, because no sooner has Veronica finished dressing herself than she blunders into the path of an oncoming car.

The girl from Hell awakens in a hospital, under the care of Dr. Max Barris (Daniel Markel). Barris isn’t sure what to make of his newest patient, since she has no discernable injuries despite being run down by a car, and doesn’t seem to be concerned about anything except the whereabouts of her “beast.” She has the strangest manners, too, as if she were not merely a foreigner, but maybe even an alien, and her interpretations of everything going on around her are always slightly, bizarrely off (like when she refers to the nurses and orderlies as “slaves”). At the same time, she knows things she shouldn’t be able to, including Max’s name. She exhibits a disconcerting ability to put herself instantly to sleep at will. And when Barris listens to Veronica’s chest through his stethoscope, he nears neither heartbeat nor lung sounds, but a chorus of human voices screaming as if in terror and agony. Nevertheless, the doctor is quite taken with the peculiar girl, and he makes no objection when she asks to be taken into his home upon her discharge the following morning. (Hellraiser, meanwhile, frees himself from the pound, and finds his way to his mistress’s side in short order.)

There are two parallel plot threads from this point on. One of them, as should already be obvious, concerns Max and Veronica falling in love, the bond between them growing stronger even as the truth of her Infernal nature comes gradually to light. The other is about what happens when a being created for the uncompromising punishment of wickedness finds herself in an environment where incessant penny-ante evil is just an accepted part of life. Once an all-night television news binge reveals to Veronica how thoroughly awash in wrongdoing even this one small city really is, she takes it upon herself to spend the hours when Barris is working his overnight hospital shift avenging that wrongdoing with all the remorseless violence of the Hellspawn she is. Her activities draw the professional attention of Detectives Harper (Mike Genovese, from Eyes of Fire and Oblivion 2: Backlash) and Greenberg (Michael C. Mahon, of Sleepaway Camp and the original Oblivion), who come to Max’s apartment to ask him about a bloody hospital smock found at the scene of the first retributive slayings, but leave rightly regarding Veronica as their prime suspect. Naturally the pressure on those two increases when the demonic vigilante begins killing abusive cops along with rapists and similar miscreants, and leaves a note promising sanguinary vengeance against the city’s crooked, callous, authoritarian mayor (Milton James, from Alien Intruder and The Stranger) on the body of one of her victims.

Whenever I find myself talking to somebody about Full Moon Entertainment, and the conversation threatens to bog down in endless belaboring of all those tedious movies about little toy monsters and little monster toys, my go-to gambit for getting things onto a more interesting track is to interject, “Okay— but have you seen Dark Angel: The Ascent?” I do that not because Dark Angel is the best Full Moon movie (although I can think of only a handful that I prefer to it), but because there’s nothing else quite like it in the studio’s catalog, and because it’s good to be reminded that even the hackiest schlock factory can sometimes surprise you with a unique flawed gem. I realize how implausible this sounds, but Dark Angel: The Ascent is one of the most thought-provoking horror films of the entire 1990’s. Far more adroitly than the more famous Prophecy series, it explores the question of what sort of culture might arise among immortal beings (or at least extremely long-lived ones; Dark Angel’s devils can be killed, and it’s unclear whether or not they ever die from natural causes) who know for a fact that God exists and demands certain things of them, no faith necessary. It deals seriously, too, with the idea of devils as fallen angels, created to execute Divine will, and possessed of an understanding of that will which no human can match. Although Satan himself never appears, and although the specific issues driving his long-ago uprising are never discussed, this movie nevertheless cannily implies that Lucifer’s fall was a phenomenon analogous in some way to that of Adam and Eve. And having done that, it raises the even more interesting supposition that a God who would set up a mechanism for the salvation of fallen humanity would be equally concerned to rescue and redeem His other fallen creations. That’s right. Dark Angel: The Ascent might be the world’s only explicitly Universalist horror movie!

That is a simply incredible level of philosophical ambition for a film that frequently operates on the surface as a supernatural hybrid of The Punisher and Ms. .45, but a lot of it just flows naturally from Linda Hassani and Matthew Bright taking a devil as their protagonist, and then running with her as far as they could in every direction available. They wouldn’t have succeeded half as well, though, without Angela Featherstone in the central role. Although she was basically just a fashion model at this point in her career, with only a few TV guest spots and nigh-invisible bit parts on her acting resumé, Featherstone displays a fair amount of genuine star power here. I’m not surprised that she blew up a little in the late 1990’s— although I selfishly wish she’d done so with more B-movie leads, instead of with supporting parts in stuff like Con Air and The Wedding Singer. Her performance as Veronica is so stylized and strange that it’s hard to get a read on her ability to play more ordinary characters, but that means she’s absolutely perfect as a devil-girl learning to navigate a world of unaccustomed moral complexity, and discovering that the Divine plan holds surprises even for the most well-informed of supernatural entities.

Alas, Featherstone is essentially alone among the cast in bringing her A-game like that— or indeed, in having such an A-game to bring in the first place. I was astonished to learn that Daniel Markel, Milton James, and the actors playing the two detectives weren’t pseudonymous Romanians angling for a transatlantic breakout, but rather a bunch of American G-listers whom Band flew out to Full Moon’s Castel Film studio in Izvorani, on the farthest outskirts of Bucharest. All of them are so bad at their jobs here that it’s natural to assume they were acting in an unfamiliar language, from a script they couldn’t actually read. The inadequacy of the supporting cast is the main reason why I’m evangelical about Dark Angel: The Ascent only with people who are already accustomed to the foibles of Full Moon productions, or whom I know to be otherwise adept at watching uneven movies for the good parts. This is one of those films that you have to meet at least halfway, but it’s extremely rewarding for those who are willing to do so.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact