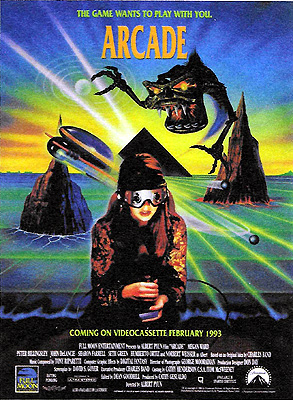

Arcade (1993/1994) *½

Arcade (1993/1994) *½

Charles Band saw himself as something of a successor to Roger Corman, who was in turn something of a successor to Samuel Z. Arkoff and James H. Nicholson. One manifestation of that self-image was that Band liked to develop his movies the American International Pictures way, starting by sketching out promotional campaigns for films that didn’t yet— and might never— exist. He’d talk these concepts up in the trade press, at industry events, and in conversation with his key business partners (Vestron Video during the Empire Pictures days, and Paramount during the first few years of Full Moon Entertainment), paying close attention to the reactions they provoked. If one of his notional projects seemed to spark interest from exhibitors, retailers, distributors, or fans, Band would hire a director and commission a script, then pretty much get out of the way unless it was something so appealing that he wanted to direct it himself. Sometimes that meant that the movies which ultimately emerged bore little resemblance to their original marketing premise, but that usually wasn’t a problem. After all, it hadn’t been a problem for AIP, either. But few films among the earliest crops of Full Moon product went as far off the rails initially laid for them as Arcade.

Band’s idea was for a humble little spooker about a haunted video arcade. 1991 was about half a decade too late for that premise to be truly exploitable, however, so director Albert Pyun (oh no…) reconceptualized the project around the hot new topic of virtual reality. Screenwriter David S. Goyer (yes, that David S. Goyer!) ran hog wild with the script, transforming Band’s $750,000 horror picture into something that Pyun himself would later characterize as “irresponsibly complex and ambitious.” But because the money was already committed, the same 750 grand would have to suffice to bring Goyer’s sweeping new vision to the screen. It should surprise nobody that Pyun failed in the endeavor, but even those familiar with his work might be taken aback by just how hard he failed. Indeed, the director abandoned ship altogether during the editing phase, fucking off to make Nemesis for a different company. The task of hammering Arcade into usable form fell to David Schroeder, Robert Barnett, and Peter Billingsley, and it took them two tries, two years, and a complete change of special effects footage before Band was satisfied. The international edition which appeared in 1993 is thus markedly different from the cut which appeared in American video stores a year later— and neither one of them is all that close to Pyun’s shambolic rough cut, let alone the film envisioned in Goyer’s screenplay. This review is based on the US release, but who knows? I might come back and revise it someday, if I ever see more of the overseas edit than the tantalizing clips shown in Arcade’s behind-the-scenes “Videozone” featurette.

Teenaged Alex Manning (Megan Ward, from Crash and Burn and Amityville 1992: It’s About Time) is a bit of a basket case. Her mother (played in flashbacks by Sharon Farrell, of It’s Alive and The Premonition) blew her own brains out last year, and Alex blames herself for reasons she doesn’t know how to articulate. Still, she’s in better shape than her dad (Todd Starks), who’s been a semi-catatonic couch potato ever since his wife’s suicide, leaving the girl effectively to her own devices. None of that is directly relevant to the bizarre situation that’s about to enfold Alex, but it will color how other characters react to her throughout. Rather, what matters directly is that Alex’s boyfriend, Greg (Bryan Datillo), and all their mutual friends are devotees of video games.

Whatever Southern California beach community this is supposed to be still has an 80’s-style video arcade called Dante’s Inferno, and it’s the place where all the not-very-cool kids hang out after school. Stilts (Seth Green, from Ticks and Idle Hands) is the first of Alex’s friends to spot the flyer advertising a special engagement at Dante’s, the rollout of a new flagship product from video game company Vertigo/Tronics. Although the title of the new game— Arcade— is none too promising, Vertigo/Tronics pitchman Difford (John De Lancie, of The Man with the Power and The Hand that Rocks the Cradle) is much better at selling the cabinet’s capabilities than it is at selling itself. Arcade is a virtual reality game, more immersive than anything of its kind yet attempted. But more importantly, the machine is able to learn from the player, adjusting its strategy and tactics to counter those of its human opponents. Nick (Death Valley’s Peter Billingsley— the same one who helped clean up Pyun’s mess after he took a powder), the techiest of Alex’s friends, is extremely impressed when he takes Arcade for a spin on Difford’s quarter, and the rest of the gang are eager to try the game for themselves thereafter. Vertigo/Tronics isn’t just giving away free preview plays on the cabinet at Dante’s Inferno, either. Difford has brought with him several prototypes of the Arcade home console, and those are the next best thing to gratis, too. All the lucky kids who turned out today need do in order to bring home their very own Arcade system is to complete the surveys included with the machines, providing Vertigo/Tronics with the real-world play-test data they’ll need to bring the consoles up to snuff for commercial release. Nick, Stilts, Laurie (A.J. Langer, of Escape from L.A. and The People Under the Stairs), and even Alex herself sign up. Greg probably would have, too, but he’s playing the cabinet all alone in the back room while Difford is handing out the prototypes, and he thereby discovers a feature of Arcade that the pitchman never mentioned. If you lose without pressing the ESCAPE key at the last moment, the game digitizes and claims you, body and soul.

Alex quickly notices that her boyfriend has gone missing, of course, but Nick, Laurie, and Stilts assure her that he must simply have gone home without her. Mind you, that requires accepting not only that Greg would leave without saying goodbye to Alex, but also that he somehow split without reclaiming his car keys from her. I suppose you could argue that he left her with both keys and car so that she wouldn’t be stranded at Dante’s without him, but it’s still weird. Alex has little trouble establishing that Greg never went home, either— not right after vanishing from the arcade, nor at any point during the ensuing evening. Eventually, to take her mind off her multiplying worries, she fires up her new Arcade console, and quickly finds herself confronting the incredible truth. The game taunts Alex about Greg’s disappearance, and even takes credit for it! She believes it, too, because somehow the game knows things about her that could have been extracted only from someone who knew her as intimately has Greg does. Alex shuts down the console at once, and rushes out to see Nick. Despite the late hour, he’s deeply engrossed in his own Arcade set when she lets herself in through his bedroom window, and he’s not at all pleased when she pulls him out of the game to relate her admittedly far-fetched story. Alex’s tale sounds a trifle less crazy, though, when not one of the other Dante’s regulars shows up for school the following morning, except for Stilts, who couldn’t get his Arcade console to work. A visit to Laurie’s house that night catches her in a zombie-like state of entrancement to the game. Alex and Nick make very little headway in getting through to her before she loses consciousness and disappears into the console before their very eyes.

Witnessing Laurie’s inexplicable fate might put Nick on the same page with Alex regarding what’s happening, but now what are they supposed to do about it? Luckily, Vertigo/Tronics is a local firm, so the kids begin by visiting the company’s headquarters. Nick bluffs their way into a face-to-face meeting with Difford, and then bluffs that into a chat with Albert (Norbert Weisser, from Midnight Cabaret and Tales of an Ancient Empire), the lead engineer on the Arcade project. It’s obvious that both men are on edge, harboring unspoken moral qualms about their handiwork, but it’s Albert who spills the important beans. The reason for Arcade’s unprecedented adaptability is that its central processor isn’t a computer at all in the usual sense. At the core of each machine is a nucleus of human neurons, harvested from the brain of a fatally abused child whose body was donated to science. Even Albert doesn’t fully realize what he and his fellow engineers have done, however. His worldview simply has no room for the idea that the game has become a conduit for the child’s vengeful ghost, haunting the virtual world of Arcade the way other unquiet spirits might haunt the houses where they were murdered or the woods surrounding their hidden graves. Albert has logged a lot of hours play-testing Arcade himself, though, and he seems to realize at some subconscious level that he’s playing the part of Dr. Van Helsing when he lets Alex and Nick in on some of the game’s secrets: the schematics of the individual levels, the nature of the hazards to be found in each, and the boons hidden throughout the game environment to help players skilled enough or lucky enough to find them. Finally, forewarned and forearmed, Alex and Nick break into Dante’s Inferno after hours to have it out with Arcade once and for all.

Albert Pyun was the last director alive who should have been entrusted with a project as low-key and cerebral as Arcade— and that would probably have been true even of Charles Band’s original concept. Pyun’s thing was action movies, and even those he directed badly more often than not. He seems totally flummoxed by Arcade, in which the most strenuous activity depicted is a leisurely skateboard ride through a maze of simulated corridors, and in which the antagonists exist only on the hard drives of a digital effects shop somewhere. The key thing here was to create buy-in for the concept of a conscious, malevolent, deliberately addictive video game, and the way to sell that was to make the surrounding normal world believable. Pyun would have to make us believe in a troubled girl describing her recurring dreams to her psychotherapist, and trying to ride herd on her emotionally crippled father. He would have to make us believe in a smarmy electronics executive ballyhooing his latest product. He would have to make us believe in two teenagers sitting together in a bedroom, talking! I think we all know that such things were lightyears beyond Pyun’s ability.

Then there’s the not insignificant matter of the game itself. Although the specifics of my criticism here would depend greatly on whether we’re talking about the US or international versions of Arcade, what I’ve been able to see of the latter suggests that the fundamental problems remain the same either way. Also, let us make allowances for the fact that computer graphics imagery was in its adolescence in the early 1990’s; besides, if ever a movie had a valid excuse for CGI that belongs in a video game, it’s this one! The trouble is not the appearance of Arcade’s virtual world, but rather that the gameplay itself is unintuitive, boring, or both. There is simply no way anyone could get excited about this turkey, let alone a bunch of veteran gamers like the kids who hang out at Dante’s Inferno. Paperboy was faster-paced and more challenging to hand-eye coordination than the opening Skateboards & Tunnels level. The Quest offered more puzzling brain-teasers than the Riddling Boatmen level or the face-to-face showdown with the Arcade avatar itself. And I frankly have no idea what the player is even supposed to do on the Wandering the Desert level! The only phase of the game that seems like it might be at all fun to play is the Tron-inspired race against the Death Riders. Unfortunately that segment, in its original form, provoked a cease-and-desist order from Disney, which set in motion the wholesale replacement of all the film’s CGI sequences. Near as I can tell, that wasn’t too much of a loss on the whole, but the Death Rider race, uniquely, was considerably better the first time around. (Turns out there are few more potent ways to spice up a cheesy video game movie than to blatantly rip off the most memorable scene from the original cheesy video game flick.) In any case, the supposed awesomeness of Arcade’s titular video game is a good example of what Ken Begg over at Jabootu’s Bad Movie Dimension used to call an Informed Attribute. It’s something that the film stridently asserts, even though all the evidence onscreen contradicts it. Even a movie with much better writing, acting, and direction than this one would have difficulty overcoming an Informed Attribute lodged at the very core of its premise, and Arcade never stood a chance.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact