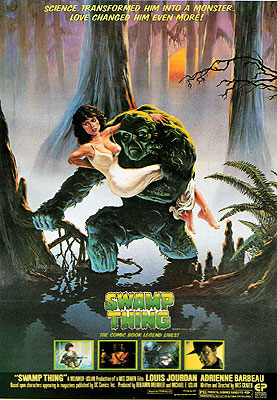

Swamp Thing (1982) **

Swamp Thing (1982) **

For the past decade or so, comic book movies have been the blockbustingest of blockbusters. The really successful ones can gross a billion dollars at the box office worldwide, and Marvel Studios especially has displayed a remarkable knack for building profitable film and television franchises around even the most minor characters in its print-publishing sister firm’s stable. Take the Guardians of the Galaxy movies, for example. Show of hands: how many of you had ever heard of that Marvel Comics super-team before 2013? I personally had previously known only of Groot— and I knew him strictly from his first career as one of Marvel’s early-60’s Underpants Monsters. That didn’t stop people from going to see the movies, though, nor did it give Marvel cold feet about giving writer/director James Gunn nine figures worth of cash to spend making each one. Let’s not forget, though, what a weird and novel state of affairs this is. Until 2008 or so, comic book movies with top-tier budgets were rare in the extreme— indeed, they were practically unheard of apart from a few Superman, Batman, and X-Men pictures. More importantly, even when there was a lot of money on the line, there was little expectation before the late 2000’s that a film based on a comic book should bother attempting to be good. Not even the rights-holders took the potential of these properties very seriously. The Cannon Group, of all companies, ended the 80’s holding the film rights to both Superman and Spider-Man, and to all appearances, the two major publishers’ asking price for most minor character licenses was something on the order of a hot meal. DC’s Swamp Thing, for example, fell first into the hands of Embassy Pictures (the outfit that brought us Billy the Kid vs. Dracula and Jesse James Meets Frankenstein’s Daughter), and then into those of the even lowlier Lightyear Pictures and Millimeter Films. The Swamp Thing’s first celluloid outing was one of the stinkers and mediocrities that Wes Craven directed in between his triumphs with The Hills Have Eyes and A Nightmare on Elm Street, and although it’s less wretched than its reputation indicates, that isn’t a very high bar to clear.

Somewhere in the depths of the Louisiana bayou stands what looks like the abandoned remains of a flooded-out church. That’s just what the place was some years ago, but its continued abandonment is a clever and carefully maintained illusion. The former church’s dilapidated exterior now conceals a state-of-the-art laboratory where sibling biologists Alec (Ray Wise, from RoboCop and Jeepers Creepers II) and Linda (Nanette Brown) Holland conduct secret research at the behest of the United States government. As Alec will put it later, he and his sister are attempting to create a plant with an animal’s aggressive drive for survival. Some might ask whether producing beakers of explosive Mountain Dew is really the most promising direction for such an undertaking, but come on. This is a cheap 80’s monster movie; beakers of explosive Mountain Dew are practically a given. One might also ask why the government is backing the Hollands’ work with the full resources of the intelligence and security apparatus, but that question has a diegetic answer that’s almost believable. Think about how a final solution to world hunger (which is how the Hollands envision the endpoint of their research) might affect the balance of Cold War power. For that matter, think about how it might be exploited by an unscrupulous captain of industry or maybe even an international crime cartel. The potential for disruption is too great for Uncle Sam not to take an intense interest in the project. And as it happens, there are rumors that somebody has got wind of what’s happening out there in the bayou even despite all the cloak and dagger, and is seeking to infiltrate the operation. That’s where federal agent Alice Cable (Adrienne Barbeau, of Creepshow and Escape from New York) comes in. Don’t ask me specifically which agency Cable works for— FBI, Secret Service, Treasury Department, who knows?— but her job is to babysit the scientists, and to keep a tight lid on the fruits of their labors.

That job is more dangerous than it sounds. In fact, the reason Cable is here in the first place is because her predecessor in the position was killed recently by an alligator while investigating some unusual readings from one of the automated electronic sensors that keep tabs on the swamp surrounding the lab. But man-eating gators are the least of anyone’s worries, because old-school diabolical genius Anton Arcane (Louis Jourdan, from Count Dracula and Ritual of Evil) has indeed been sniffing around after the Hollands, and he’s got a man on the inside. Worse yet, the mole is Arcane himself! For who knows how long, the evil mastermind has actually been overseeing the whole project, impersonating Ritter the program head (Don Knight, of Death in Space) with the aid of a Mission Implausible disguise mask. So no sooner do the Hollands make what looks like a critical breakthrough than Arcane summons his private army to overrun the laboratory. The takeover goes less smoothly than Arcane would have liked, however. His men are forced to shoot Linda to prevent her from fleeing with all of the laboratory notes, and Alec is killed, too, in a more spectacular manner a moment later. The final version of the Holland superweed formula is extremely volatile, and it explodes all over Alec when he attempts to keep it away from Arcane’s goons. His body ablaze from head to toe, Holland charges out of the lab past the villain’s understandably flustered mercenaries, and hurls himself into the black water of the bayou (for all the good that does him). There’s no question but that this is a setback for Arcane— both scientists dead, the only sample of the final Holland formula lost— but at least he has the notebooks in which the Hollands recorded their findings and experiments. He gathers up the latter, and orders his men to destroy the lab, leaving neither survivors nor witnesses.

That turns out to be a bigger challenge than expected. Cable not only fights her way past Arcane’s soldiers, but manages to swipe and conceal the crucial final notebook while she’s at it. Arcane entrusts the job of rounding her up to a squad under the command of Ferret (David Hess, from Zombie Nation and Hitch-Hike), but that goes even more haywire than the seizure of the lab. It isn’t that Ferret and his boys can’t find Cable— although that does take them the rest of the night and most of the following morning. The problem, rather, is that something keeps finding them, and picking them off one by one until only Ferret and one other man named Bruno (Nicholas Worth, of The Glove and Dark Angel: The Ascent) remain alive. Nor is that Cable’s doing; she’s good, but she isn’t that good. The mercenaries’ bane is a hulking, humanoid creature that seems somehow to be made out of the swamp itself— moss and mud and tree roots all bound together into something powerful, invulnerable, and intelligent enough to spring a fatal ambush on a trained soldier of fortune.

Cable sees the creature (gangly-limbed stuntman Dick Durock, who played another big, green monster in an episode of “The Incredible Hulk” around the same time) as well when she sneaks back to what’s left of the lab to retrieve the hidden notebook. The marsh monster seems to be pantomiming working with the Hollands’ equipment, oddly enough, but it gets frustrated upon discovering that its hands are too clumsy and brutal to handle glass laboratory ware without smashing it. Somehow, though, the creature does manage not to wreck the locket wherein Linda kept cameos of herself and Alec, which it finds amid the wreckage and reverently drapes over the branches of one of the Hollands’ surviving experimental subjects. This is our first major clue that the Swamp Thing is really a transformed Alec Holland. Cable doesn’t seem to catch on just yet, but Arcane might be forming a suspicion along those lines, at least if we can judge from his new orders to Ferret demanding the capture of the creature along with the G-woman. Arcane has also discovered by now that he’s missing a notebook, and although he never says so directly, it may be that he believes the Holland formula could be reverse engineered by vivisecting the Swamp Thing.

Between Alec’s continued intervention and the help of an adolescent bayou-dweller named Jude (Reggie Batts), Cable is able to keep a step or two ahead of Ferret and Bruno for a while. Indeed, Alec kills Ferret when the two of them finally meet again at close quarters. Ferret gets a good hit in before going down, though, hacking off Alec’s arm with a machete. The Swamp Thing’s life is never in danger (it’s hard to kill a tree by cutting off its branches), but the injury weakens him sufficiently for Bruno and the remaining Arcanettes to get the better of him. With her protector defeated, Cable at last falls into Arcane’s custody, and the final notebook along with her.

A few nights later, Bruno learns just how little the boss’s gratitude is really worth. With the Swamp Thing’s identity as Alec Holland confirmed, Arcane begins rethinking his plans for the scientist’s creation. What if, instead of using the Holland formula to seize dominion over the agricultural sector of the world economy, Arcane were to expose himself to it directly? Could he become a super-being like the Swamp Thing? Arcane didn’t get where he is by being the “hold my beer” type, however, so he decides to give this new idea a trial run. At the banquet he throws in celebration of his triumph at his mansion on the bayou (who the hell are all these party guests, anyway?!), he contrives to spike Bruno’s drink with a dose of the Holland formula. But far from becoming superhuman, Bruno dwindles and contorts into a hunched, goblin-like creature barely four feet tall. Obviously a consultation with the formula’s inventor is in order, so Arcane stomps down to the dungeon where he’s been keeping Alec and Alice. Wearily, Holland explains that Arcane has missed the whole point of what his formula does. It isn’t a superizing compound at all. Instead, it amplifies the essence of whatever is exposed to it— “It makes you more of what you already are.” Now Arcane gets it. “Bruno’s essence was stupidity, timidity,” he muses, “But if the essence of the subject were instead genius…” And with that, he runs upstairs to mix himself an aperitif.

Cable, meanwhile, has had a brainstorm of her own. Arcane’s dungeon isn’t entirely closed off from the outside world. Near the ceiling of the cell she shares with Alec is a tiny window, and now that the sun is setting, a ray of light has shown through it to illuminate a spot just above the Swamp Thing’s head. Holland’s transformed body is more plant than animal, right? And plants get their energy from photosynthesis, right? Well, maybe Alec would get his monstrous mojo back if he reached up into that sunbeam to let his chlorophyll soak up its power. Holland reckons it’s worth a try, and sure enough, no sooner do his fingers find the light than a fresh, green shoot begins growing from the stump of his arm. The question is, which process proceeds faster— Alec’s recovery or Arcane’s transformation? Arcane might think his essence is genius, but the thing taking shape inside that cocoon in the master bedroom suite looks more like the personification of greed or rapacity or treachery to me. I wouldn’t want to be around when it hatches, even if I were seven feet tall and made of cellulose.

The Saga of the Swamp Thing (subsequently retitled just Swamp Thing) was one of the pivotal comic books of the 1980’s. It was Alan Moore’s launch vehicle to international stardom, and the instrument whereby he began forging DC’s unprofitable stable of unpopular occult characters into the pantheon for a coherent and compelling pop mythology. It provided a model for how to do supernatural horror in a mainstream comic milieu without merely copying the EC anthologies of the early 50’s one more time. And perhaps most importantly, it became, beginning with issue 29, the first DC title to reach the newsstand without the seal of the Comics Code Authority, enabling it to take on subject matter that had been explicitly forbidden by industry self-censorship for some 30 years. Knowing all that, it’s basically impossible to watch Wes Craven’s Swamp Thing without some degree of disappointment. Where’s the Green? Where’s the Parliament of Trees? Where are all of Swamp Thing’s cool nature elemental powers? This is just an 80’s update of the old American International Pictures monster programmer formula!

Yeah, well… The reason why none of the stuff that makes Swamp Thing special is in this movie is because none of it had been invented yet. DC launched The Saga of the Swamp Thing in tandem with this film, hoping the two versions would be mutually reinforcing, even if they differed with each other in detail. Craven’s source material was therefore not The Saga of the Swamp Thing, but the original Swamp Thing series from the 1970’s. As originally written by Len Wein, the Swamp Thing was basically just a more highly evolved version of an obscure 1940’s comic book muck-monster called the Heap. He was big and strong and virtually indestructible, but his bimonthly series had never served up anything more sophisticated than two dozen variations on the “itinerant misunderstood monster” trope, even despite the Swamp Thing’s human personality and genius-level intelligence. Craven’s Swamp Thing is a fair enough interpretation of Wein’s, and viewers of the film should adjust their expectations accordingly.

The trouble is, Swamp Thing the movie has difficulty meeting even that significantly lower standard. For the purposes of a misunderstood monster story, Craven and company render the Swamp Thing both insufficiently misunderstood and insufficiently monstrous. The central misstep is that the movie seems fundamentally unclear on whether we’re supposed to realize that the Swamp Thing is really Alec Holland before he reveals his identity to Cable. On the one hand, there are plenty of clues leading up to that. The beaker-smashing scene is the most obvious, but the creature’s unmistakable protectiveness toward Cable should probably be almost enough all by itself. The Swamp Thing spends the whole second act doing virtually nothing but laying the smackdown on Arcane’s mercenaries, all the while leaving Cable conspicuously unmolested. Beyond a certain point even a Bruno should catch on that the creature is choosing its targets deliberately. Then there’s the simple fact that the Swamp Thing enters the picture immediately after Alec leaves it. I mean, it’s not like there’s a preexisting legend about a monster haunting the bayou to encourage any alternate interpretation. We know, alright? And yet Craven insists upon giving us only a victim’s-eye view of the transformed Holland until just a couple of scenes before his capture, as if he wanted us to believe that the Swamp Thing were no more than a threat even deadlier than Ferret.

All Craven really accomplishes by holding Holland at arm’s length after his transformation is to sabotage any subsequent effort to build anew the relationship between him and Cable. To be sure, the pairing was never terribly convincing even when Alec was human, because Ray Wise and Adrienne Barbeau (who is otherwise a definite highlight of the film) have about as much chemistry together as gold and helium. And to be even surer, the second go-round for Alec and Alice had strikes against it from the outset because Dick Durock’s 6’5” height was his sole qualification for the role, and because the Swamp Thing suit was a rubbery travesty that would have thoroughly defeated even a much more capable actor. But regardless of the suit’s limitations, and however good, bad, or indifferent the key performances, Craven quite simply never allows himself the time to sell the audience on a friendship with option for romance between a woman and a literal human vegetable. He’s too busy showing the Arcanettes being terrorized. Cable and the Swamp Thing need more scenes together at the very least, and they could probably do with a top-to-bottom restructuring of the whole second act.

Harder to spot than the spongy characterization of the Swamp Thing himself or the unpersuasiveness of the Holland-Cable relationship, but arguably coequal to them in the damage it wreaks on the picture, is the cascading fallout from the initially trivial-seeming decision to collapse Nathan Ellery and Anton Arcane— the two recurring villains of Len Wein’s Swamp Thing run— into a single character. In the comics, Ellery was, for all practical purposes, a Bond villain. He led an ill-defined criminal organization with vaguely implied aims, employed a private army of paramilitary goons, and wielded an unlikely arsenal of high-tech weapons and equipment. And his efforts to steal the secrets of Holland’s Bio-Restorative Formula set in motion the events that turned Alec into the Swamp Thing. Ellery even had henchmen named Ferret and Bruno! Arcane, on the other hand, was a monster-making wizard from some Balkan Bullshittia, located no doubt on the border between Transylvania and Mordor. His interest in the Swamp Thing stemmed from his ardent desire for immortality, together with his weariness of and contempt for the human condition. He wanted to install himself in Holland’s invulnerable vegetable body, whether by Frankensteinian super-surgery or by straight-up magic— and when that didn’t work, he turned himself into a superhuman monster by other means. Combining these two into a single character requires that the Holland formula be able to satisfy both of their aims, and that’s how we arrive at the ludicrous notion that a chemical designed to create “a simple vegetable cell with an unmistakable animal nucleus” somehow works by “amplifying” the subject’s “essence.” The latter idea leads to the even more ludicrous notion that Holland, by transforming into a humanoid lichen with the strength of a bull rhinoceros, somehow becomes more of what he already was. Revamping the title character’s origin into flagrant nonsense even by comic book standards seems like an awfully high price to pay for an excuse to climax on a monster fight.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact