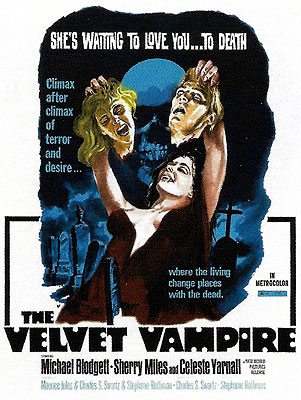

The Velvet Vampire / Cemetery Girls / The Devil Is a Woman / The Waking Hour (1971) **½

The Velvet Vampire / Cemetery Girls / The Devil Is a Woman / The Waking Hour (1971) **½

Most of the time, there’s no serious possibility of mistaking an American exploitation movie for a European one. The styles are too starkly different, and while Continental filmmakers often do attempt to ape Hollywood, the reverse almost never happens. Stephanie Rothman’s The Velvet Vampire is a striking exception to the rule, however. You could slip it into the middle of a program of Eurocult sex-horror flicks by the likes of Jean Rollin, Jose Larraz, and Sergio Martino, and only the true connoisseurs would have much chance of spotting the difference.

Somewhere in Los Angeles, in the kind of district that shuts down almost completely when the last of the office workers goes home for the day at 6:00 PM, a beautiful young woman (Celeste Yarnall, from Eve and Beast of Blood) is walking alone at night. The only other person on the streets there is an outlaw biker (Robert Tessier, of The Sword and the Sorcerer and Future Force), who figures the lack of bystanders is as good an excuse as any to rob and/or rape her. The biker has miscalculated, however. Although he seems to gain the upper hand over the girl quickly and easily enough, no sooner does he get the top two buttons of her blouse undone than she shivs him in the lung with his own knife. The “victim” gets up to wash the biker’s blood from her hands in a public fountain, then continues on her way as if nothing out of the ordinary had happened.

Stone-Cold Rapist Shanker’s name is Diane Le Fanu, and her destination is an art show at the Stoker Gallery, where she’s a regular customer. At the gallery, the eponymous Carl Stoker (Gene Shane, from Run, Angel, Run and Werewolves on Wheels) introduces her to two of his other regulars, Lee Ritter (Michael Blodgett, of The Trip and Beyond the Valley of the Dolls) and his wife, Susan (Sherry Miles, from The Todd Killings and The Pack). Lee instantly pops a boner for Diane that can be detected from low Earth orbit, and makes no effort to conceal the situation from Susan. Mrs. Ritter, however, is a passive-aggressive pushover who would rather have a grievance to nurse than be satisfied, so she raises no objections when Lee accepts an invitation for the pair to spend the coming weekend at Diane’s ranch in the desert. Or at any rate, Susan raises no objections when doing so might have accomplished something. She throws a sulk for the ages when she and Lee get back to their apartment, though, you’d best believe that!

Nevertheless, Friday afternoon finds the Ritters driving eastbound into the desert as planned. At the gas station that seems to be the last outpost of civilization in that direction, Lee manages to quarrel with both the owner, Amos (Sandy Ward, of Terminal Island and Cujo), and Cliff the mechanic (Paul Prokop, from Dream No Evil and The Peace Killers), so it pretty much serves him right that his car breaks down about halfway to nowhere later. Luckily, Diane happens to be zipping around the arid wasteland in her dune buggy at the time, and she comes upon her stranded guests long before they start facing any real danger from the unforgiving elements. Once at the ranch, Lee and Diane again flirt shamelessly in front of Susan, who again saves up her irritation to spring on her husband after they’ve gone to bed.

Some other things that happen after Lee and Susan retire for the night stand to be much more meaningful for their future than his insensitive tomcatting, however. The room in which Diane has put them up has an enormous mirror covering much of one wall. This mirror is of the kind they have in police interrogation rooms, and on the other side of it is a secret chamber from which Diane spies on her guests. She quite enjoys the show when Lee goes down on Susan as a peace offering, even if Susan is still too peeved with her husband to reciprocate. Then after the pair fall asleep, they have inexplicably identical dreams in which their lovemaking in an unfamiliar bed in the middle of the desert is interrupted by Diane, who emerges from an incongruously placed mirror and interposes herself between them. Each dreamer interprets the action a little differently, however. To Susan, it seems that Diane is pulling Lee away from her, while Lee feels himself pushed toward Diane by Susan. But the most disquieting event of Friday night doesn’t directly involve Lee or Susan at all. When Diane put in the call to Amos’s gas station to have the Ritters’ crippled Mustang towed away for repairs, she must have asked for some work to be done on her own vehicle as well. Cliff the mechanic made a rather startling house call to perform the latter work while Diane and her guests were having a late dinner. He’s just about finished a few hours later when Diane barges in and comes forcefully on to him. Cliff tries to resist her advances, but all that gets him is the threat of a pummeling from Diane’s Indian handyman, Juan (The Norseman’s Jerry Daniels). Juan and Diane chase the mechanic around the garage for a bit, but the altercation ends unexpectedly with Cliff tripping over a pile of cardboard boxes, and falling onto the tines of a pitchfork.

Saturday morning finds the Ritters being rousted from bed before dawn for the sake of some sightseeing in the deep desert. (They’ve got to start early, because it isn’t safe to be out there when the sun is high in the sky.) The first attraction is an abandoned mine, which Diane says was given up in the 1870’s not due to the ore running out, but rather because of an unexplained rash of killings down in the tunnels. Miners kept turning up with their throats cut until finally no one would go down there anymore. The Ritters have a scare of their own when they somehow get separated from Diane in the old mine. Lee then foolishly separates from Susan to go looking for Diane, and he’d probably still be blundering around those tunnels in the dark were it not for Susan screaming in response to having been found by someone or something herself. The someone or something in question turns out to be Diane, but after what we saw last night, I’m not sure that would have helped Susan any if Lee hadn’t been so fast in retracing his steps. Then again, Diane saves Susan’s life later that morning, so who knows? While her hostess and her husband poke around the ghost town of Miragosa (and poke around under each other’s clothes), Susan lies down to sunbathe, and somehow manages to get herself bitten by a sidewinder. Luckily, Diane knows the old B-Western “slit the wound and suck out the venom” trick. The lingering effects of the bite leave Susan bedridden for the rest of the day, however, so she misses out on a third excursion, this time to the 19th-century Mexican cemetery where Diane buried her late husband. That’s what keeps Diane living out in this hostile nowhere, it turns out. She had Victor embalmed via a technique known only to the local Indians, which relies heavily on the dry desert air. If ever she were to have the body reburied conventionally, it would decay at once.

Diane’s communion with the deceased is intruded upon by Cliff’s girlfriend (Chris Woodley), who has figured out that the dead mechanic was last seen on his way to the weird woman’s ranch. She is not persuaded by Diane’s claim to have called the station to cancel her appointment, nor is it lost on the girl that this supposedly disused old boneyard has acquired a fresh and unmarked grave. Cliff’s girlfriend returns to the site in the evening to excavate said grave, and yup— that’s Cliff, alright. But while the bereaved girl was absorbed in her work, she failed to notice Diane and Juan sneaking up on her. It’s the last mistake she’ll ever make, and her death confirms at last something that we’ve suspected since reading the fucking title. Diane and Juan don’t just kill the potential troublemaker. Rather, Juan holds the girl down while Diane bites her on the throat to feast on her blood. Then she opens up her husband’s grave (the earth above it is but a few inches thick, concealing a stout trap door), and spends the rest of the evening lounging sadly atop the coffin.

Evidently reminiscing about past love at the bottom of a grave puts Diane in the mood for the present-tense variety under less morbid conditions. When Lee awakens in the middle of the night from a recurrence of the desert lovemaking dream (which we’re now given to understand is being somehow beamed into the Ritters’ brains by their hostess), he finds her waiting for him in the living room. Susan wakes up soon thereafter, and catches them in the act. As is her wont, however, she says nothing at the time, even after Diane makes eye contact with her spying on the tryst from the bottom of the stairs. This incident marks the turning point of the couple’s strange weekend in the desert, but not at all in the way you’d naturally expect. Having gotten what she wanted from Lee, Diane starts concentrating her energies on seducing Susan. Mrs. Ritter, for her part, is only too game to give a bit of tit for her husband’s tat, while he, in his jealousy, finally begins to notice all the myriad signs that Diane is up to no good. And although Lee may have the proactive temperament to insist that they leave the ranch at once, Diane’s attentions seem to have given Susan the willpower to stand up for herself at last. What they clearly haven’t given her is the sense to recognize when she’s being manipulated, or the instinct for self-preservation necessary to do anything about it on the off-chance that she did…

Stephanie Rothman having been the director and scenarist of The Student Nurses, it’s only natural to search The Velvet Vampire for signposts to a radical feminist interpretation. What I find most interesting about this movie, on a subtextual level, is that the signposts are there, but they mostly lie. What Diane offers Susan isn’t female liberation, even when she explicitly presents it as such. I mean, Diane herself remains in thrall to the memory of a man a hundred years dead, despite having killed him with her own hands. If she’s found liberation out there in the desert, it’s of a totally traditional sort that American mythology has always associated with the frontier, the liberation of having nobody around to tell one what to do. There’s nothing specifically feminist about that. It’s easier to argue, however, the aspect of Diane’s freedom which she now proposes to share with Susan and Lee is at least fairly radical. For what Diane is offering is the possibility of love without rules. Out on her ranch, there’s nothing to get in the way if she wants to have a ménage-a-trois with both members of a married couple, while simultaneously getting it on with both her handyman and the century-old mummified corpse of her husband. Indeed, there’s nothing to get in the way of anything that tickles Diane’s amorous fancy, and that could go for the Ritters as well. It’s a seductive proposition for a pair of young people just beginning to sort out the personal implications of the Sexual Revolution, but notice that Lee and Susan don’t buy into it equally. Lee initially jumps at Diane’s pitch, but in the end he needs love and sex to have rules after all— he just wants them not to apply to him. The reversal of the Ritters’ attitudes toward their hostess comes precisely when they each separately realize that Diane’s invitation extends to both of them.

Of course, there’s a second catch, too. When Diane says no rules, she means no rules. That means no consent. That means no obligation to consider the other party’s needs or desires. If Diane wants to spy on her guests from behind a one-way mirror, or use her paranormal abilities to intrude on their dreams, then that’s just what she’ll do. And if her vampiric blood-hunger should come over her in the middle of some sexual frolic, then that’s just too bad for her partner. Furthermore, Diane has grown so twisted in her isolation that there needn’t be any hard feelings behind such a murder. Again, look at what happened between her and her husband. For the Ritters, this is both a direct, physical danger and an oblique, moral one. On the one hand, it means that associating with Diane exposes them to a constant yet unpredictable risk of being casually murdered. And on the other, it makes surrendering to the allure of her lifestyle a one-way ticket to Monster Island. If we consider the latter a test of character, then Lee and Susan each score about a D+.

I said before that The Velvet Vampire resembles a European sex-horror film, and what I mean by that above all else is that the effectiveness of its style greatly exceeds that of its substance. It’s a film of arresting beauty, composed with a painter’s eye and designed with a decorator’s touch. Rothman and cinematographer Daniel Lacambre turn the Mojave Desert, Diane’s ranch, and Celeste Yarnall herself into a Russian doll of gorgeous death-traps, each recapitulating the others on a different scale. The siesta-hour languor of The Velvet Vampire’s pacing contributes to a powerful sense of place, as if the movie itself were afraid of baking to death under the severe Southern California sun. At the same time, narrative logic and character motivation are slippery and elusive, bearing very little scrutiny. And that goes double for the film’s vampire lore, which I frankly don’t feel as though I understand at all. All in all, it’s best to let The Velvet Vampire just wash over you, without trying to grab hold of any of its details.

Unfortunately, that would be a lot easier if it weren’t for Sherry Miles. Susan Ritter was always going to be a difficult character to like, or even to tolerate, but Miles’s clamorously artless performance makes it simply impossible. When she speaks, she’s like a human dental drill; when she doesn’t, her attention-hogging facial mugging is almost worse. Combine both of those things with a characterization that requires her to whine and/or pout for fully two thirds of her screen time, and the result is a distraction that the rest of the cast and crew must strain every sinew to overcome. Inevitably, they often don’t succeed. Without Miles, The Velvet Vampire would earn my unhesitating recommendation for any fan of Eurocult erotic horror. With her, it becomes a dicey question.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact