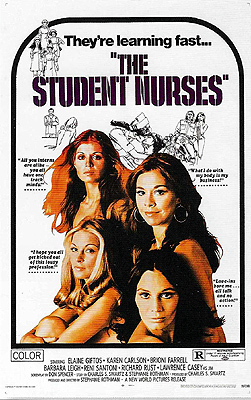

The Student Nurses (1970) **½

The Student Nurses (1970) **½

Roger Corman had been with American International Pictures from the very beginning, since before there technically was such a company as AIP. The American Releasing Corporation was founded in 1955 on a three-picture deal between Corman acting as independent producer, and Samuel Z. Arkoff and James H. Nicholson acting as would-be studio bosses. But in the second half of the 60’s, Corman fell increasingly under the influence of counterculture types like Jack Nicholson, Dennis Hopper, and Bruce Dern, growing ever more sympathetic to the concerns of hippies, druggies, bikers, and student radicals, even if he never joined their ranks as such. Arkoff and Nicholson did not. They were content to release movies about long-haired weirdoes so long as they kept making money, but Nicholson especially wasn’t comfortable having their names on anything that seemed to agree with that perspective or to approve of that lifestyle. On The Wild Angels, they pushed Corman to tell the story from the townspeople’s point of view instead of the bikers’, although Corman won that argument. When Corman made The Trip, the studio heads altered the final cut to make the film read less like an endorsement of LSD. But the real breaking point was Gas-s-s-s. Jim Nicholson was horrified by that film’s irreverent attitude toward patriotism, religion, the military, and just about every other facet of American culture, and while Corman was away in Ireland directing Von Richthofen and Brown for United Artists, Nicholson had Gas-s-s-s extensively recut. Corman didn’t find out what had happened until he caught a screening of his picture at the Edinburgh Film Festival during some downtime on the Von Richthofen shoot. It was the last time he ever directed for AIP, although he would produce a few more movies for Arkoff and Nicholson afterward to satisfy contracts already signed.

When you know that story, it becomes much easier to understand how Stephanie Rothman’s The Student Nurses happened. This was the inaugural feature for Corman’s own company, New World Pictures, and the first of what turned into a whole cycle of “sexy nurse” movies that persisted throughout the 70’s. It’s also one of the most politically motivated and avowedly radical exploitation films I’ve ever seen. It deals not merely with sex, drugs, and hippydom, but also with issues like abortion, male chauvinism in the workplace, sexual exploitation within the counterculture itself, and the systemic mistreatment of Mexican immigrants. The Student Nurses would never have been allowed at AIP, and I have to believe that Corman was acutely conscious of that when he gave Rothman the green light to make this, of all possible pictures, as his new company’s first. It’s easily missed, and therefore not much talked about, but there was a utopian streak running through New World Pictures in the early days. Sure, the company was a sleaze factory run by a notorious cheapskate, but it was also a place where the receptionist could become the next film’s leading lady, or one of the set fabricators the director of something three or four films down the line. For all its catering to masculine libidos and fantasies of violence, New World offered extraordinary opportunities to women behind the camera, employing female writers, directors, producers, story editors, attorneys, sales and development executives, and so on at a time when most of Hollywood had no off-camera jobs for women outside the secretarial pool. (Just the same, you wouldn’t see Corman bucking the system when it came to the wage gap between male and female employees. I said that New World had a utopian streak, not that it was a utopia.) Most of all, New World Pictures was a place where people who aspired to make more than tawdry exploitation flicks were free to run as wild as they dared— provided the finished product could still be sold as a tawdry exploitation flick. The Student Nurses set that pattern. The four titular young women have lots of sex along the way, but the movie is really about them figuring out how to be adults in an era when all the rules and traditions governing such things have fallen to shambles.

Housemates Priscilla Kovac (Barbara Leigh, from Mistress of the Apes and Terminal Island), Phred Stella (Karen Carlson), Sharon Armitage (Elaine Giftos, of Angel and Gas-s-s-s), and Lynn Verdugo (Brioni Farrell, from Project Metalbeast and Appointment with Fear) are all nearing the end of their final year in nursing school. There isn’t a one of them who quite knows what she means to do with her life afterward. I mean, they figure they’ll go on healing the sick and injured, obviously, but as to where and under what circumstances, most of them haven’t a clue. Phred is the least undecided. With her intense horror of death, she knows that anything like oncology or shock trauma isn’t for her. That’s half the reason why she’s pleased when Miss Boswell (Scottie MacGregor), the head of the nursing program at the training hospital where the girls are all studying, informs her that her last posting before graduation will be to the obstetrics and gynecology unit— not a lot of mortality in OB/GYN, right? The other half of the reason is Dr. Jim Caspar (Lawrence P. Casey, from The Daughter of Emmanuelle and The Erotic Adventures of Robinson Crusoe), the department’s new resident and a very attractive man in the straight-arrow, junior-chamber-of-commerce way that Phred likes so much.

Priscilla, assigned to the psychiatry unit for her last rotation, prefers a different sort of guy: edgy, rebellious, a little arrogant, hip to the counterculture if not necessarily a full-fledged member of it. She finds just what she’s looking for at the pan-Asian café where she eats lunch one day, when a long-haired pseudo-sophisticate by the name of Les (Richard Rust, of Naked Angels and Homicidal) notices her noticing his motorcycle. Over the ensuing days, Les takes her for chopper rides, escorts her to a love-in (or maybe it’s a happening— I confess that I never quite sorted out the difference), and does a variety of other hippyish things with her. At one point, he even takes her to a secluded beach to have sex while tripping on LSD. Unsurprisingly, Pricilla’s relationship with Les causes some friction between her and Phred, especially when the lack of privacy at the nurses’ house brings Les and Jim into contact. Neither man has much patience or respect for the other, although Les seems to irritate Jim more than vice versa.

Sharon, on pediatrics duty, isn’t looking for love at all. Instead, she winds up forming a rather fraught, albeit mostly platonic, personal bond with a teenaged cystic fibrosis patient named Greg (Darrell Larson, of Android and Futureworld). Greg has been living with the looming specter of his own impending death since before he was old enough to understand what that meant. He’s outlasted the earliest prognosis about his chances by some eight years, but the way he sees it, you can’t really call what he did during all that extra time “living.” Shit, for most of it, he’s been cooped up in the chronic ward of this or that hospital. Understandably, Greg is an angry kid, and he has a tendency to take out his frustrations with the crappy hand he got dealt on anyone who has the temerity to show pity for him. That puts Sharon in an uncomfortable position, because caring for Greg is now literally her job, and she feels like she’s not doing it right if her heart doesn’t go out to her patients.

Lynn, finally, draws public health as her terminal posting. That means she pulls her shifts on the hospital’s various community outreach programs, like vaccination drives and free clinics for the indigent. Miss Boswell warns her, however, that the public health gig entails the maximum possible exposure to liability, and advises her to be a nurse only when she’s on the clock. Because of her training, and because she is a hospital employee, a spontaneous good deed gone awry is as good as an express ticket to Malpractice Suit City. That warning is at the forefront of Lynn’s thinking when a fight breaks out at a demonstration she encounters while walking to work, leaving one of the protestors seriously hurt. Lynn slips away as quietly as she can, but she just happens to wind up assisting the surgeon when the injured man’s friends bring him to the free clinic for treatment. Feeling guilty as fuck, she tracks down the guy who seemed to be in charge of the protest (Reni Santoni, from Radioactive Dreams and Cobra) to apologize for not stepping forward at the scene to perform first aid. The rabble-rouser in question calls himself “Victor Charlie” (“’Cause I’m the Enemy.”), and he publishes the underground newspaper La Causa de la Raza; I gather it’s a Maoist/Zapatista kind of thing. Victor gives Lynn a bunch of shit for not speaking Spanish even though her last name is Verdugo, and generally raises the shit out of her consciousness. Or at any rate, I’m sure that’s what he thinks he’s doing. Remarkably enough, however, Lynn does indeed decide that this is a guy who understands where it’s at, to the extent that she starts getting involved in Latino radicalism herself.

What’s really interesting about The Student Nurses is that each of the four housemates gets in way over her head with whatever her situation is, making the kind of mistakes that would lead straight to the square-up reel in any normal movie, but none of them is ever really punished for her actions. When Les knocks Priscilla up, and the hospital psychiatric review board won’t grant her a legal abortion on mental health grounds (remember that this was three years before Roe v. Wade), she convinces Jim to perform one for her on the downlow. The operation is a complete success even though Priscilla has an acid flashback in the middle of it, and while Phred (who is strenuously opposed to abortion) is furious with all concerned, she refrains from finking on either Priscilla or Jim. Phred breaks up with Dr. Caspar after that, shifting her affections to his roommate, Mark (Meteor’s Paul Camen), but everyone is able to handle the transition like an adult despite considerable hurt feelings all around. Sharon faces no official consequences for a colossal breach of professional ethics when she finally does become Greg’s lover during the last weeks of his life. The closest she comes to even a verbal reprimand is a stern reminder from her main teacher, Dr. Warshaw (Richard Stahl, of Beware! The Blob and Good Against Evil), that grieving over a patient is a luxury that no nurse or doctor can afford. Even Lynn gets away Scot free when Victor and the rest of the Causa de la Raza staff become embroiled in a shootout with the Los Angeles police, and she drives the getaway car for them. Indeed, as the credits roll, she seems positively excited about spending the rest of her life as an outlaw being hunted all over the Southwest!

The best way to get a handle on The Student Nurses, and on how it differs from later, more typical sexy nurse (or sexy teacher, or sexy stewardess) movies, is to say that it’s about the closest thing I’ve seen to an American I Am Curious film. As with Vilgot Sjöman’s notorious diptych, it uses sex to liven up what could become a very tedious examination of social issues from a basically leftist perspective, and it seems likely to drive a wedge between viewers who come to it looking for titillation, but get turned off by all the politics, and those who feel that its political aims would be better served without the distracting influence of all the sex. There’s a fundamental difference, however, between I Am Curious and The Student Nurses. Sjöman was a completely independent auteur, making exactly the movies he wanted to. Stephanie Rothman, on the other hand, was working for Roger Corman, and therefore had to account for the tastes of the exploitation market. That is, she was in the seemingly impossible position of making a feminist movie for sale to people overtly hostile to feminism, a Marxist movie for sale to people overtly hostile to Marxism, and in general a political movie for sale to people overtly hostile to politics. That she succeeded is astonishing. How she succeeded without years’ worth of obscenity trials to bolster people’s interest in her work is a mystery that turns what could and perhaps should have been a negligible film into an unforgettable one.

Part of it, I think, is simply that Rothman was completely sincere about all this stuff, at a time when a critical mass of young people were, too. That is, horny kids would come for the pretty girls taking off their clothes (plus, significantly, a couple of not-bad-looking guys), and discover a film that treated their search for identity and meaning with the utmost sympathy and earnestness. If I’m right, it’s vitally important that each of the protagonists goes looking for what she needs in a different place, and that none of them is certain that she’s actually found it come graduation. And it’s probably equally important that a wide spectrum of values is on display, from Phred’s desire merely to personalize the belief system in which she was brought up all the way to Lynn’s eventual embrace of full-blown, cop-shooting radicalism. It’s also noteworthy that The Student Nurses acknowledges the prices carried by all the alternatives it examines, without staking out any clear position on which of them are or are not worth paying. Some might accuse Rothman of feckless moral relativism on that score, and they wouldn’t be entirely wrong. But if the question is, why did people go in for this movie when what it delivers is so different from what it promises, then that willingness to give the benefit of the doubt to even the bloodiest excesses of its era’s youth rebellion has to be in the picture somewhere. And so does the lack of facile romanticism about what comes of making the choices its heroines do. You want to stay on the margins of the straight and narrow in revolutionary times? Then be ready for plenty of friction with your peers who want to push harder than you. You want to pursue experience for its own sake, trying each new thing that comes before you just because you can? Then don’t be surprised when a certain percentage of your experiments blow up in your face, depriving you of things you can never get back. You want to take the Beatles at their word, and hurl love and compassion at everyone who crosses your path? Then know up front that some of those people are going to treat you like shit anyway, and that you’ll feel loss all the harder when it inevitably hits you. You want to change the world for your idea of the better, no matter what it takes? Then reconcile yourself to the possibility that it might well take violence, and remember that violent lives end in violent deaths. These aren’t punishments The Student Nurses posits for its characters’ actions— they’re consequences. There’s a difference, and the most appealing thing about this movie is that it assumes we’re smart enough to know what it is.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact