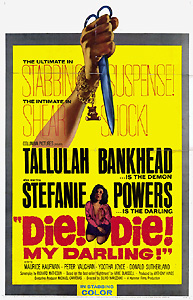

Die, Die, My Darling!/Fanatic (1965) **˝

Die, Die, My Darling!/Fanatic (1965) **˝

Though the studio is, of course, best remembered for its long association with gothic horror, Hammer Film Productions also made throughout the 1960’s (and even a little way into the 1970’s) a succession of psychological thrillers intended to ride the coattails of American hits like Psycho and Whatever Happened to Baby Jane?. With titles like Maniac, Paranoiac, and (as Die, Die, My Darling! was known in its country of origin) Fanatic, it wasn’t exactly difficult to guess which market segment these movies were aiming for, and I have to admire the forthrightness of studio boss Sir James Carreras in openly referring to the films as his “mini-Hitchcocks.” Die, Die, My Darling! came just about smack in the middle of the cycle, and was in some respects the most ambitious of the lot. While most of its predecessors were shot from well-crafted but derivative scripts by Hammer stalwart Jimmy Sangster, and featured nobody more significant than Oliver Reed or Kerwin Matthews in front of the camera, Die, Die, My Darling! brought in some awfully impressive names from outside the studio’s usual stable. The screenplay was written by Richard Matheson from Anne Blaisdell’s novel, Nightmare, but the bigger coup was Hammer’s success in coaxing Tallulah Bankhead out of retirement to do for them what Bette Davis and Joan Crawford had done for Warner Brothers in Whatever Happened to Baby Jane?. Sadly, however, Die, Die, My Darling! falls somewhat short of realizing its ambitions, due to some jarring tonal shifts and an almost total failure by the rest of the cast to rise to the challenge of Bankhead’s performance.

Someone who caught only the first act of this movie on television, without seeing either the title or the stylishly portentous opening credits, might be forgiven for assuming that Die, Die, My Darling! was a comedy of manners in a mid-60’s update of the age-old British tradition. Patricia Carrol (Stefanie Powers, later of Crescendo and Invisible Strangler) returns to London after a long sojourn in the United States, accompanied by her new TV producer fiance, Alan Glentower (Maurice Kaufmann, from Psycho-Circus and The Vault of Horror). The two expatriates have come home to be married, but Patricia has something she feels she must do before that happens. You see, this is not the first time Patricia has been engaged. Her previous fiance, Stephen Trefoile, died some years ago in a car crash (which Pat believes was not an accident, but suicide), and although she has never met or even so much as corresponded with the old woman, she believes she owes it to Stephen’s mother to drop in and pay her respects to the past before launching off on her future with Alan. Alan, for his part, is not happy with this plan. Part of it is surely a typically masculine reluctance to face up to the fact that his partner had lovers before him, but at the same time, it’s difficult to argue with Alan when he says that he fails to see the point of the venture. I mean, it’s not like Patricia and her almost-mother-in-law were ever close. Nevertheless, Patricia refuses to be dissuaded. Leaving Alan at his place of work, she zips off to the Trefoile house out in the hinterland, saying she’ll be back in town by noon tomorrow.

Mrs. Trefoile (Bankhead), as if you couldn’t have guessed this, is the fanatic of the original title. She had been a Broadway actress in her youth, but she was “rescued” from that life of sin and debauchery when she married a Royal Army officer (now deceased) who must have been the most God-awful stick in the mud in all of Britain. Emphasis on the “God,” there, by the way. The late Colonel Trefoile was of the opinion that any sort of physical pleasure or worldly happiness was inherently sinful, and somehow he managed to bring his wife around to his way of thinking. There are no mirrors in the Trefoile house, so as not to encourage vanity. Anna, the Trefoile maid (Yootha Joyce, from Horrors of Burke and Hare, who also had a very small role in Frankenstein: The True Story), is under strict orders to make all the food as bland as possible. Life in the Trefoile household is rigidly organized around a schedule of marathon religious services conducted by Mrs. Trefoile herself. (She hasn’t been to her local church in several years, strenuously disapproving of the current rector’s “lax” attitudes.) So I’m sure you can imagine the social fireworks when Patricia, liberated woman of the 60’s that she is, foolishly makes herself a guest in Mrs. Trefoile’s de facto convent, and finds herself expected to abide by its “divinely ordained” rules. Patricia is too polite, however, to do the sensible thing, and storm off to her car in a huff. Instead, she grits her teeth and acquiesces when her hostess flips out over her wardrobe and makeup, invasively quizzes her about her personal history, shanghais her on a visit to Stephen’s grave, and makes lots of presumptuous pronouncements about leading her out of “error.”

The first third of the movie plays all that stuff mostly for laughs, but there is a creepy undercurrent that becomes stronger and stronger as the film wears on. Not only does the title (and the simple knowledge of what sort of picture this is supposed to be) lead us to assume that Mrs. Tefoile’s over-the-top religiosity is more sinister than it seems at first glance, there is another character under the old lady’s roof who is plainly going to be nothing but trouble from the word go. This is Anna’s husband, Harry (Peter Vaughan, of Symptoms and Time Bandits), who happens also to be Mrs. Trefoile’s last living relative. Harry’s interest in his aunt or cousin or whatever she is to him is a matter of pure greed, for the old lady is very rich, and has nobody but him upon whom to bestow her considerable property after she dies. Naturally, this means that Harry must be at great pains to downplay his nature as a lecherous, conniving, immoral sleazebag, although concealing it completely is well beyond his power. And Anna doesn’t trust him at all around Patricia. Of course, neither Harry nor his somewhat reluctant benefactress would be a problem for Pat if she were really going to take her leave of the Trefoile place on the morrow, according to plan. The thing is, though, that Mrs. Trefoile has a plan of her own. So far as she’s concerned, once two people are engaged, they’re as good as married in the eyes of the Lord. Furthermore, because anybody worth marrying in the first place will surely be going to heaven, it only stands to reason that husbands and wives can count on being reunited in the afterlife; that, in turn, means that the death of a spouse (or a fiance, for that matter) is no excuse for breaking one’s marriage vows. In other words, Mrs. Trefoile still considers Patricia to be her daughter-in-law, and she’s determined to see that the girl remains faithful to Stephen up in heaven— even if that means keeping her prisoner in Colonel Trefoile’s old bedroom. And if Patricia maintains her stubborn insistence upon behaving sinfully… well, let’s just say that Mrs. Trefoile isn’t about to turn down a good brainwashing technique just because it was invented by militant atheists, nor is she necessarily above taking a few steps to hurry the reunion between her son and his former fiancee along a little. Harry, meanwhile, isn’t above anything.

It’s difficult to overstate what an utter stroke of genius it was to cast Tallulah Bankhead as Mrs. Trefoile. This is not so much because of the quality of her performance, but rather simply because of who she was. In the late 1920’s and early 1930’s, when Hollywood pretty much really was the vast den of vice and perversion that people like Joseph Breen believed it to be, Bankhead still managed to distinguish herself for her rowdy and “immoral” behavior. She was a copious consumer of bourbon and tobacco at a time when both of those indulgences were considered to be un-ladylike in the extreme, and she was well known for being that girl at the party who somehow can never manage to hang onto her clothes for the full duration of the evening. To cast this hard-drinking, chain-smoking, exhibitionist scandal machine as a dour and obsessive arch-puritan is both a complete inversion of what anyone would have expected and the perfect way to enrich the character’s back-story. When Mrs. Trefoile talks about how her husband rescued her from damnation by getting her out of the acting business, a viewer who is familiar with Bankhead’s background will immediately think, “Yeah, well maybe she kind of has a point.” At the very least (assuming, of course, that we really are meant to infer that Trefoile’s youth resembled Bankhead’s), the stuffy old bugger almost undoubtedly saved her from lung cancer, liver failure, and a venereal disease or two. Furthermore, Bankhead is indeed quite good in the part, even if she’s basically just riffing on the formula that Bette Davis established three years earlier. What puts her in the same league as Davis at her best, and several cuts above the run-of-the-mill middle-aged she-ham of the 1960’s, is her Vincent Price-like ability to calibrate her overacting precisely to the requirements of the material. It’s a blustery, flamboyant performance Bankhead puts in here, but it’s also exactly what the role demands.

Unfortunately, nobody else in the cast has anything like the wattage necessary to compete with the star. That’s rather surprising, too, because Die, Die, My Darling! has a couple of very capable actors in its supporting cast, once you get past the colorless lightweights playing Patricia Carrol and Alan Glentower. Most conspicuously, a very young Donald Sutherland has a moderately important part as Mrs. Trefoile’s retarded handyman, Joseph, but the role is too small and the character too limited for him to do much of anything with it. Of course, with Sutherland’s career thus far confined to films like Castle of the Living Dead and Dr. Terror’s House of Horrors, it’s hardly surprising that Hammer’s casting people would fail to recognize how much talent they were allowing to lie fallow. Peter Vaughan’s eclipse is more difficult to fathom. Vaughan was a veteran character actor, and actually, he holds his own quite well so long as Tallulah Bankhead is nowhere to be seen. My guess is his regular acting style is just too naturalistic not to get swamped in the wake of Bankhead’s scenery-chewing.

What doesn’t seem natural at all is the way Die, Die, My Darling! lurches between comedy and horror, and this is probably the movie’s most serious failing. Bear in mind that this is not at all a black comedy in the usual sense of the word. Better to say that it is an otherwise fairly conventional psychological horror film that curiously comports itself like a comedy for the first half hour or so. Now, radical mood swings of this sort can indeed work, and when they do, the result is often breathtaking— witness Takashi Miike’s Audition for what might be the ultimate illustration of the point. In Die, Die, My Darling!, however, director Silvio Narizzano fumbles the transition between emotional polarities in a way that I can’t quite put my finger on. Maybe it’s because the very title— either title, really, but especially the original Fanatic— so clearly telegraphs what’s coming. In any case, something makes it much too obvious from the get-go that Mrs. Trefoile is a grade-A nutter, that Patricia will wind up as her prisoner, and that some manner of attempt will be forthcoming to speed the post-mortem reconciliation between Patricia and the deceased Stephen on its way, and in the face of that obviousness, none of the humor in the first act is able to create the illusion of innocence that seems to have been the aim. Instead, it feels as though Die, Die, My Darling! is simply killing time, and time is one thing that ought never to be killed in a suspense movie.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact