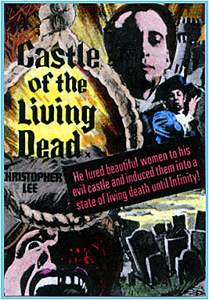

Castle of the Living Dead/Crypt of Horror/Il Castello dei Morti Vivi (1964) **½

Castle of the Living Dead/Crypt of Horror/Il Castello dei Morti Vivi (1964) **½

An interesting sideline of movie history that has not attracted nearly as much attention as it should is the wide array of different measures which the various national film industries of the world adopted to solve technical problems that confronted them all, and the seemingly inordinate impact those divergent solutions could have on the development of cinema in each country. For a particularly instructive example, consider how the American and Italian industries responded to the challenge of sound. In the US, early, imperfectly successful experiments with sound dubbing convinced the leadership of most studios that it was not a viable means of adding spoken dialogue to motion pictures. The studios therefore sank huge amounts of time, effort, and money into developing synch-sound, the technology for recording a movie’s audio track in synchronous with the exposure of the film itself. The dissatisfaction with dubbing also led to such collateral developments as Universal’s short-lived practice of mounting Spanish-language parallel productions of their movies for export to Latin America (the most famous example being the Spanish-language version of Dracula). It was only after several years of tinkering that the science of audio dubbing became advanced enough to be accepted in this country, by which point synch-sound was at such a level of maturity that only the most cash-strapped producers would consider post-production dubbing. The Italian movie industry, on the other hand, embraced dubbing from the outset, and that acceptance had surprisingly widespread effects on the way things were done on Italian film sets. For one thing, dubbing encouraged multinational casting. After all, it didn’t matter if the actors— even the lead players— couldn’t speak a word of Italian, because their lines were going to be overdubbed anyway, and natives could always be hired to do the job if the imported stars proved to be totally hopeless. Indeed, by 1963, it was becoming commonplace to have the entire cast reciting their lines in English on the set, as the English-speaking market— the American television market in particular— was at that point accounting for the lion’s share of the industry’s profit, outweighing even the huge domestic Italian box-office. Another curious side-effect of dubbing arose when Italian production companies hired stars from Britain or the United States in the interest of enhancing a film’s overseas marketability. In Italy, it was standard operating procedure for actors to give two performances, one for the camera and another for the microphone, but performers accustomed to synch-sound often perceived this as an attempt by the producers to get double the work for a single paycheck. Christopher Lee and Barbara Steele were especially well known for refusing to play the game by the Italians’ rules, leaving their dialogue to be recorded by others after they went back to England at the end of the shoot. And that, at last, brings us to the subject of Castle of the Living Dead. This obscure Franco-Italian co-production marks one of the few occasions on which Lee allowed himself to be persuaded to stick around for the dubbing phase.

Following an exceptionally eye-catching credits sequence involving masses of weird stone statuary and a theme song so perfect that it really deserves to be attached to a much better movie, a voiceover narrator sets the stage for us. The Napoleonic Wars have ended, leaving the whole of Europe overrun with demobilized conscript soldiers. This unprecedented horde of surplus fighting men threatens to destabilize society nearly as badly as the wars themselves had, as thousands of them turn to brigandage and piracy rather than returning home to practice their former trades. Crime is rampant, safety in the open countryside is almost non-existent, and public hangings are common occurrences. In fact, one of them is happening right now. The convict (Luciano Pigozzi, from The Whip and the Body and Baron Blood), curiously enough, is dressed in harlequin’s motley, and the executioner (Jacques Stany, of Four Flies on Grey Velvet and Women’s Prison Massacre) is having the damnedest hard time getting his neck into the noose— the man simply won’t cooperate, and the noose keeps slipping out from under his chin. Exasperated, the executioner steps up on the stool himself to demonstrate the proper way to wear a noose, and the convict kicks the stool out from under him, hanging him instead. It’s all a trick, though. As we now see, the two men on the scaffold are members of a troupe of itinerant entertainers, and the noose has been rigged so as to be harmless to its victim. The hangman is really Bruno, the leader of the troupe, the slippery harlequin his longtime colleague, Dart. The other performers are Bruno’s sister, Laura (Gaia Germani, from Hercules in the Haunted World and Devil in the Brain), a hulking deaf-mute named Johnny (Luigi Bonos, of The Evil Eye and Frankenstein ‘80), and a dwarf named Nick (Anthony Martin, who I’m about 90% certain is the same person as the Skip Martin we’ve seen before in Vampire Circus and The Masque of the Red Death). All is not friendship and harmony among the entertainers, however, for Dart is of the opinion that the money-obsessed Bruno has been cheating him out of his fair share ever since he joined up. The festering resentment is brought to a head when Sandro (60’s bit-part guy Mirko Valentin, whom the sharp-eyed may see in The Virgin of Nuremberg and Hercules Against the Barbarians), a servant of the local lord, announces that his master will pay three gold pieces for the privilege of watching Bruno’s showmen run through their act at his castle. Dart picks a fight with Bruno right in the village tavern, attacking him with a broken bottle. Luckily for Bruno, one of the other patrons is Eric (Philippe Leroy, from The Libertine and Naked Girl Killed in the Park), an erstwhile captain in Napoleon’s army who now has nothing better to do than hang around in pubs and ingratiate himself to protagonists by administering beat-downs to bad guys. Laura and Bruno, in gratitude for the rescue, invite Eric to join up with them in Dart’s place.

On the way to the castle to fulfill their unprecedentedly lucrative engagement, the gang encounter two very odd things. First, Nick halts the wagon to draw attention to the curious silence of the surrounding woods, leading to the discovery of what appears to be a taxidermized raven perched on one of the lower branches of a tree beside the road. Then the performers are accosted by a hunchbacked old lady (Donald Sutherland, from Dr. Terror’s House of Horrors and Buffy the Vampire Slayer, in drag and heavy makeup) who speaks in rhyme and claims to be able to foretell the future. The hag warns the travelers to stay away from “the castle of the living dead,” and prophesies death within the next 24 hours for at least someone among them. Bruno and Eric both scoff, but Laura is profoundly creeped out by the encounter, and Nick takes the old woman seriously enough to trade her some food for a supposedly protective charm.

Unsurprisingly, that castle of the living dead is the very one to which Bruno and his companions have been called to perform. Perhaps to the disappointment of most modern audiences, the living dead are not zombies here, but rather the alarmingly lifelike preserved carcasses of seemingly every animal in the surrounding wood, which are mounted throughout the castle in every imaginable style. The mastermind behind this macabre riot of taxidermy is the owner of the castle, Count Drago (Christopher Lee), also the man who has hired Bruno and his friends for the evening. Drago would never be so crass as to demand his show before the performers have had dinner, however, and so he orders Sandro to show the troupe to their rooms and put the kitchen staff to work. The count also does a bit of entertaining himself, showing Bruno around the laboratory where he preserves his inanimate pets and explaining the secret to his greatest successes: while sojourning in the tropics, he accidentally discovered that the secretions of a certain plant not only killed but also instantly embalmed any form of animal life. Drago also mentions that he has begun working on a new project, one that involves the preservation of “the most interesting and dangerous animal species of all.”

Those of you who’ve seen The Most Dangerous Game or any of its countless knockoffs will not need me to tell them what that phrase is code for, and will know even before Bruno begins feeling the effects that the cognac Drago gives him is poisoned. The drug is slow-acting, however, and to all outside appearances, it ought to look as though Bruno attempted the hanging trick while falling-down drunk and strangled himself for real by accident. Laura nevertheless suspects foul play, although it is not Drago whom she fingers as the most likely culprit. Remembering Dart’s parting threat that “when you feel the rope around your neck, I’ll be there,” Laura thinks the disgruntled harlequin sabotaged the trick noose so that it would work like the standard model. Her suspicions are reinforced when Dart turns up at the castle, prowling around presumably in search of revenge. That complicates matters a bit for Drago, for when Sergeant Paul (also Donald Sutherland) and his two constables drop in for their periodic check on the castle, the count has little choice but to admit that a crime has been committed under his roof. Fortunately for him, Sergeant Paul is a deeply stupid man, and is easily thrown off the scent. Once he and his men have moved on, Drago can get back to the serious business of laying snares for his guests unobserved. Now the only thing standing in his way is that witch from the forest, who has secretly contrived to maintain contact with Nick, and who has a grudge of her own against the count.

I think what really sold me on Castle of the Living Dead, allowing me to overlook the shambling pace, plot-hole-riddled screenplay, and atrocious dubbing for everyone other than Christopher Lee, is the simple fact that the dwarf gets to be the hero. Sure, Eric does the sword-fighting at the climax, but Nick is the one who figures out first among the survivors that somebody other than Dart is killing off the members of Bruno’s troupe, and who takes Drago down by finally giving the witch her longed-for inroad to the castle. Without Nick, the best Eric and Laura could have hoped for would be to get arrested by those numbnuts policemen, who return to the castle just in time to see Drago fencing with Eric, and leap to the conclusion that the ex-soldier is the criminal. (And while we’re on the subject, it bugs the hell out of me that the whole stupid business could have been averted if Laura had found it within herself to interrupt her cowering long enough to shout, “No, you assholes! Not him— the count!!!!” Some fucking heroine she is…) I’m pretty sure this is the only time I’ve seen a dwarf get to save the day, and that gives me the warm fuzzies for this movie, which otherwise doesn’t do a lot to deserve them. Still, the premise is pretty cool (albeit kind of a let-down in light of the title), there are a few good performances that cut through the interference of the dubbing, and Castle of the Living Dead looks wonderful overall, despite obviously having been either shot on the shoddiest available film stock or processed by the most woefully inept development lab in Italy. No classic, but well worth a look.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact