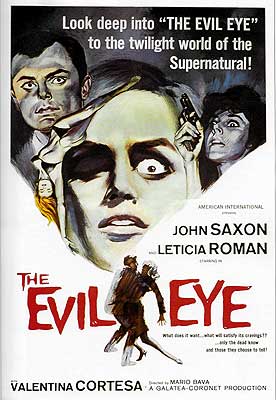

The Evil Eye / The Girl Who Knew Too Much / La Ragazza che Sapeva Troppo (1963/1964) ***

The Evil Eye / The Girl Who Knew Too Much / La Ragazza che Sapeva Troppo (1963/1964) ***

Rather startlingly many years ago, my fellow B-Master, Dr. Freex, described The Last Man on Earth as “Zombie Movie Zero.” I might have misread him, but I’ve taken that to mean that although The Last Man on Earth isn’t properly a zombie movie— hell, there aren’t even any zombies in it!— it nevertheless marked out the parameters within which virtually all subsequent zombie movies would operate until the present day. The Evil Eye occupies a similar position relative to the giallo. Blood and Black Lace may be the first, but this is Giallo Zero, and any serious discussion of the genre as a whole must encompass The Evil Eye as well, even as it stands conspicuously apart from what came later.

Nora Davis (Fanny Hill’s Leticia Roman) loves murder mysteries. In fact, she’s reading one as we meet her, on a transatlantic flight to Rome to visit her ailing Aunt Ethel (Chana Coubert). Nora’s taste in literature matters because the habits of mind that it encourages go a long way toward explaining her reactions to the events that enfold her at her destination, beginning when the smarmy glad-hander who sat beside her on the plane is arrested at the customs desk for trying to smuggle a briefcase full of cocaine and marijuana into the country. The man in question had given Nora a pack of possibly doctored cigarettes while unwelcomely flirting with her earlier, and rather than just keeping them in her pocket until she gets a chance to dispose of them in private like a sensible person, she launches into thriller-heroine mode, and makes a big production of “stealthily” dropping them while she waits in the customs line herself. She’s just lucky the airport cops are less imaginative and paranoid than she is, because one of them notices her contrived accident, and hands the suspicious cigs back to her!

At Aunt Ethel’s house on the Piazza di Spagna, Nora finds the old lady under the care of Dr. Marcello Bassi (John Saxon, from Prisoners of the Lost Universe and Queen of Blood). Dr. Bassi explains that the patient is suffering from a weak heart, and he makes sure to acquaint Nora with her aunt’s medications before returning to the hospital for the night shift. That turns out to have been a wise precaution, because Ethel has a massive heart attack just as Nora is getting into bed. Unfortunately, the girl isn’t quick enough with the drugs, and her aunt dies on the spot. The telephone, meanwhile, is only slightly less dead, leaving Nora to choose between walking to the hospital to fetch Dr. Bassi and spending the night in a strange house with a corpse in the next room. Despite having been warned at least twice that Rome is a dangerous city for girls traveling alone, Nora picks the former option— and is so unconcerned about it that she doesn’t even bother to get dressed first, simply donning a short overcoat directly over her virtually non-existent negligee. Just barely is she out the front door when she is set upon by a mugger, who knocks her out and absconds with her purse. Something even worse confronts her when she comes most of the way around a while later. On the other side of the square, she sees a woman (Marta Melocco) stagger out of the shadows with a knife in her back, only to be dragged off again by a bearded, middle-aged man (Giovanni Di Benedetto, of Blood and Roses and The Bird with the Crystal Plumage). That’s much too much for Nora to handle in her weakened state, and she lapses back into unconsciousness.

It rains all night long, and Nora is substantially the worse for wear come morning. A passer-by (Dante Di Paolo, from Blood and Black Lace and Samson and the 7 Miracles of the World) attempts to revive her with a shot of liquor from his hip flask, but scampers off when he spots a policeman approaching. Concussed, bedraggled, half-naked, reeking of alcohol, and raving about a murder all evidence of which was washed away by the overnight downpour, Nora makes a very poor showing for herself before the beat cop. He not implausibly takes her for an alcoholic whore suffering from delirium tremens, and drops her off at the hospital which she had been trying to reach for Aunt Ethel all along. Of course, the doctors there are much readier to accept the patrolman’s version of events than Nora’s, and it isn’t until Dr. Bassi happens along that her adventures in the Franz Kafka Memorial Health Service come to an end. Even Marcello vouching for her isn’t enough to get the her story about witnessing a murder believed, however. Dr. Bassi is inclined to attribute the frightening scene to a combination of high emotion and the blow to Nora’s head from the mugger, while the police inspector called in at her insistence (Titti Tomaino) quickly dismisses her as a foolish, hysterical female who needs to lay off the paperback crime novels.

Nora and Marcello start seeing a lot of each other after he gets her sprung from the psych ward, to the point that a romance develops between them. One of their first dates, if you can call it that, is Aunt Ethel’s funeral, where Nora meets the dead woman’s next-door neighbor, Laura Craven Torrani (Valentina Cortese, from The Iguana with the Tongue of Fire and The Possessed). Laura too gets close to Nora, and even invites her to move into her house for a while. You see, Laura’s professor husband has been called away from Rome on extended business, and she intends to follow shortly with her niece and nephews. Someone will have to look after the house, and anyone can see that Nora is uncomfortable staying in the place where her aunt died. Win-win situation, right? Nora sees the sense in that, and soon her new friend is leading her on a tour of the domecile, showing her all the things she’ll need or want during her stay. The one part of the house Laura doesn’t bring Nora to look at is the professor’s study, but that needn’t concern her. Dr. Torrani keeps it locked all the time, anyway, and there’s no key but the one he always carries with him. Nora doesn’t let on at the time, but that business about the locked room sends her into thriller-heroine mode again. And although she’s in no position to realize this herself, there’s good reason this time. On a desk in the study, there’s a framed photograph of Professor Torrani, and he’s the guy Nora saw dragging the murder victim away on that dreadful first night in Rome.

Sure enough, things turn threatening once Nora ensconces herself in the Torrani house. A man begins following her around town at a discreet distance. Scary prank phone calls torment her almost every night. And one evening, Nora finds a box of newspaper clippings in a closet, detailing a rash of long-ago crimes known in the press as the Alphabet Murders. All three of the killings were committed within a short distance of the Torrani place, and the final victim— the “C” victim— was Emily Craven. That’s Craven as in Laura’s maiden name, for in fact she was Laura’s sister. Nora’s discovery gives her some new ideas. What if it wasn’t just the rain washing away the blood and the bearded man disposing of the body that eliminated any evidence of the murder she witnessed in the Piazza di Spagna? According to the old newspaper clippings, that was the very spot where Emily Craven was slain a decade ago. What if Nora saw, in effect, the ghost of Emily’s murder— the psychic residue of her death agonies? Mind you, Nora’s never had a psychic flash before, so there must be some special reason for it if that’s what’s happening to her now. And that puts Nora in mind of her own surname: Davis. The clippings from the closet don’t say what became of the Alphabet Killer. What if he’s still out there somewhere, thinking about going back into business? These worries freak Nora out so badly that she spends the rest of the evening booby-trapping the house, which yields farcical results when Marcello and a familiar beat cop drop by separately but simultaneously to check on her.

The next mysterious phone call Nora receives is clearly more than just a prank. The caller stays on the line long enough to give directions to a dilapidated boarding house, where she will supposedly learn the truth of the situation she’s blundered into. Nora believes she goes alone to investigate, but actually she’s been followed by Marcello; when he reveals himself rather artlessly at a moment of extreme tension, I think you’ll agree that he pretty much deserves the mauled cheek to go with the broken finger he got from Nora’s trap the night before. Anyway, what they find at the boarding house is not the mystery caller, but a taped message from him warning Nora to go back home to America lest she suffer the same fate as Laura’s sister. The night’s adventure is not completely unproductive, however. The room with the tape recorder turns out to be leased by one Andrea Landini— a name which Nora recognizes from the by-lines of the articles on the Alphabet Murders. A pity those clippings have all inexplicably vanished now that they might be potentially useful as evidence…

Unexpectedly, Landini soon seeks Nora out directly. In fact, he’s waiting for her in the Torrani house when she and Marcello return from an afternoon at the beach. And although Nora doesn’t realize this, they’ve met before— Landini was the passer-by who tried to jump-start her system with a slug of booze while she lay unconscious in the Piazza di Spagna. He’s also the prowler who’s been keeping tabs on her. You see, Landini is obsessed with the Alphabet Murders, and justifiably so. When the police attempted to railroad an obviously innocent man over the killings, Landini vowed to solve the crimes himself, reporting on his progress via his daily news reports in the hope of shaming the cops into doing their jobs correctly. Eventually, the reporter came up with a suspect of his own, and the case he made was so convincing that the authorities ultimately bought into it. Landini’s man was convicted, and spent the rest of his life in a hospital for the criminally insane. Just recently, though, Landini stumbled upon new evidence exonerating the convict beyond any plausible doubt. Wracked with guilt, the reporter is now more determined than ever to find the real culprit, and he has become convinced that a new round of Alphabet Murders is about to begin— if it hasn’t begun already. If Landini, Nora, and Marcello joined forces, they might just be able to save… well, who knows? How about a life for every letter of the alphabet, in a worst-case scenario? Soon after that pact is made, though, Landini turns up dead in his own flophouse hotel room, surrounded by evidence implicating him as the Alphabet Killer. Savvy mystery fans will see at once that this too is a frame-up, however. The picture it paints is too tidy, yet fails at the same time to account for several important clues. I mean, we already know that Professor Torrani has to be mixed up in this somehow, regardless of whether what Nora saw in the piazza was happening then or ten years earlier.

The Evil Eye’s bizarre and lurching tonal shifts between suspense and mordant humor make a lot more sense when you know that it was originally supposed to be pure comedy, a spoof of the Alfred Hitchcock thrillers that were then selling almost as many tickets in Italy, proportionally speaking, as they were on their home turf. Even the original title— which translates to The Girl Who Knew Too Much— takes on a fuller and more cogent meaning with that in mind. Some semblance of the initial premise can still be discerned in the completed film, which often comports itself like a Northanger Abbey for pulp detective fiction. Nora is so devoted to crime thrillers and murder mysteries that she interprets the events of her real life according to their genre tropes, and it may well be that the script as written included no genuine present-day murder plot at all. As it is, The Evil Eye still teases us once or twice with the possibility that the killing in the piazza was nothing more than the result of Nora absent-mindedly smoking some of her airline seat-mate’s loco weed. (Or at any rate, the international cut does. American International Pictures’ US cut removes all reference to drugs so as not to piss off the parents of their teenaged target audience.) Mario Bava was one of those filmmakers for whom a screenplay was never more than a set of loose guidelines, however, and in his opinion, this one was too absurd to be taken seriously as comedy. That is, to shoot the film as intended would produce something that was merely silly and puerile— but raise the stakes with a serious threat to the protagonist and few scenes of genuine horror, and the humor becomes correspondingly darker and richer. The soundness of Bava’s instinct in that direction is shown to best effect in the early hospital scene, where an extended riff on Hitchcock’s oft-used theme of mistaken identity and misinterpreted circumstances is simultaneously exaggerated to ludicrous extremes and given real bite by Nora’s experiences of the night before. After all, the girl has already been mugged, witnessed a murder, spent the night passed out in the rain, and had her favorite aunt die horribly right in front of her because she was too slow on the draw with the nitroglycerine drops. Why wouldn’t she wind up unjustly imprisoned in a psychiatric hospital, too?

Unsurprisingly, it’s in those scenes of horror and suspense— even the ones that get deflated as the setup to a gag— that The Evil Eye reveals both its relevance to the emergence of the giallo and the respects in which it doesn’t fit the genre’s mature paradigm. On the side of similarity, it almost suffices to point out that Dario Argento would lift the mechanics of this movie’s conclusion practically whole for Deep Red: the protagonist, mistakenly believing the mystery solved, unexpectedly comes face to face with the real killer, who then calmly and considerately explains everything before going on the attack. Equally giallo-like is the feint in the direction of the paranormal that comes when Nora briefly considers that she might have picked up a psychic echo of the final Alphabet Murder. For a genre that theoretically eschews the supernatural, the gialli of the 70’s would devote an awful lot of attention to clairvoyance, ESP, tarot cards, and the like. The convolution and credulity-straining nature of The Evil Eye’s plot would be flattered by many imitators in the decade to come, marking the one point on which this movie might have been more influential than the comparatively straightforward Blood and Black Lace. Most of all, the focus on amateur sleuthing in competition with or effectively in place of official crime-solving efforts would become an increasingly important feature of gialli as they emerged from the shadow of the German Krimis.

Before we delve seriously into the ways in which The Evil Eye isn’t a giallo, it’s worth making an important but easily overlooked historical point: film noir never really took root in Italy. The earliest experiments in that style weren’t screened there because of wartime trade restrictions, and from the late 40’s through the mid-50’s, Italian filmmakers were busy with Neo-Realism. By the time the industry was ready to let its hair down in the late 50’s, peplum and sci-fi were in fashion, followed by period adventure, gothic horror, and still more peplum in the first half of the 60’s. As a consequence, giallo might be thought of as what the Italians belatedly did instead of noir. Certainly giallo’s embrace of scummy characters and moral cynicism has plenty in common with film noir, however different the two forms are in terms of story conventions, thematic emphasis, and visual style.

What all that has to do with The Evil Eye is that I’ve never seen another Italian movie that looked so much like film noir. At bottom, the noir look was all about applying the techniques of German Expressionism, as filtered through early-30’s Hollywood gothic, to crime melodramas with contemporary urban settings. That’s exactly what Mario Bava did in this film, too. As his last black-and-white picture, The Evil Eye marks the culmination of everything Bava had done and learned as a cinematographer, director, and lighting coordinator on The Devil’s Commandment, Caltiki, the Immortal Monster, and Black Sunday. But The Evil Eye’s moral universe lacks the weary nihilism of film noir, nor still less is it the sanguinary human jungle of Blood and Black Lace and the subsequent true gialli. Nora Davis is a good kid, just as most of the Hitchcock heroes and heroines are fundamentally good people, and the film ends with goodness triumphantly reaffirmed. In the gialli, goodness frequently doesn’t even exist.

The other big difference between The Evil Eye and a proper giallo concerns the handling of the murders. If we discount Aunt Ethel’s death from natural causes, only four people are killed in this film— and two of those are murderer and accomplice slaying each other. Nora’s hands remain clean even of deserving blood in the end. (Again, this is the original edit I’m describing. The AIP cut replaces the concluding gag about Nora’s tainted cigarettes with a much darker one in which she, having learned her lesson about meddling in crimes that don’t involve her, turns a blind eye to an enraged cuckold gunning down his wife and her lover.) Furthermore, the only one of those murders we’re allowed to see occurring is that of the Alphabet Killer. It’s a quick, easy, bloodless kill, too— a far cry from the atrocities that would be inflicted in vivid, bleeding color the next year in Blood and Black Lace. Ironically, far and away the grisliest death in The Evil Eye is Aunt Ethel’s, in which we are privy to every grimace and spasm as her heart locks up on her for the last time. As a consequence, The Evil Eye mostly stays well to the thriller side of the horror-thriller frontier, the crossing of which is arguably the giallo’s main reason for being.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact