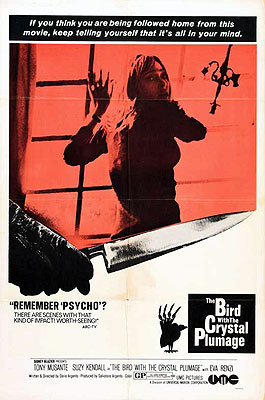

The Bird with the Crystal Plumage / The Gallery Murders / Point of Terror / The Phantom of Terror / L’Uccello dalle Piume di Cristalo (1970) **½

The Bird with the Crystal Plumage / The Gallery Murders / Point of Terror / The Phantom of Terror / L’Uccello dalle Piume di Cristalo (1970) **½

It absolutely baffles me that Blood and Black Lace not only bombed in Italy, but wasn’t particularly successful anyplace else, either, except for West Germany. That’s how it happened, though, so Mario Bava’s pioneering giallo attracted comparatively few imitators at home during the remainder of the decade. But then in 1970, a young screenwriter by the name of Dario Argento tried his hand at directing with a film called The Bird with the Crystal Plumage. Like Blood and Black Lace, The Bird with the Crystal Plumage blurred to the point of total effacement the dividing line between murder mystery and psycho-horror, and did so with a visual panache that rendered the logical shortcomings of its story all but irrelevant. Argento found audiences in a more receptive mood than Bava had, however. The Bird with the Crystal Plumage became an international sensation, and within months, Italian theater screens were crawling with black-gloved killers, and exhibitors were scrambling to cram ever longer and more convoluted titles (The Iguana with the Tongue of Fire! The Bodies Show Signs of Carnal Violence!! Your Vice Is a Locked Room, and Only I Have the Key!!!!) onto their marquees. Nor was The Bird with the Crystal Plumage alone among the gialli of the 70’s in securing lucrative distribution deals abroad. A few were screened even as far afield as Japan and Thailand! Furthermore, the new gialli proved as influential as they were successful, forming a crucial (if often unacknowledged) foundation for the slasher movies that dominated horror cinema in the early 80’s. And of course some slasher auteurs did acknowledge their debt to the gialli. Most notably, John Carpenter was once quoted describing Halloween as his “Argento movie.” All that baffles me, too, because there’s barely a thing The Bird with the Crystal Plumage does that Blood and Black Lace didn’t already do better.

To its credit, The Bird with the Crystal Plumage begins by showing us something that I can’t recall ever seeing anywhere else— the enormous amount of prep-work necessary to be a successful Black Glover. Along with a brief demonstration on the proper selection, care, and maintenance of knives and straight razors and the importance of a lair suitably isolated from prying eyes, we get a behind-the-slashing look at how much time and effort goes into staking out even the most randomly chosen victim. Whoever has it in for Sandra Roversi (Annamaria Spogli), they take great pains following her about Naples to determine her routine, surreptitiously photographing her and studying the places she frequents in order to set up the perfect ambush. Evidently this is the third girl this killer has targeted thusly, and all that meticulous preparation has paid off handsomely thus far. Inspector Morosini (Enrico Maria Salerno, from The Warrior Empress and Hercules and the Captive Women) will later lament that there’s no pattern apparent in the crimes, no discernable connection between the victims, and no useful physical evidence obtainable from any of the murder scenes.

We should bear all that in mind when struggling American author Sam Dalmas (Tony Musante) witnesses what looks on the surface like an attempt at a fourth such killing on his way home from the Wilkinson Institute, where he had just picked up his paycheck for a work-for-hire gig writing an overview of the organization’s work on rare-bird conservation. As Dalmas passes by an art gallery, he sees through its plate-glass display window a red-haired woman (The Amorous Adventures of a Young Postman’s Eva Renzi) struggling with a black-clad figure. The latter scampers off through a door apparently leading to the gallery’s basement after noticing Dalmas watching, leaving the woman gut-stabbed but still alive. Alas, it’s after hours and the front door is locked, so Sam can find no means of entering the building to help her stay that way. All he can do is to dispatch another passer-by to summon the police while he stands watch. The good news is that official help arrives in time to save the victim— who turns out to be Monica Ranieri, the wife of gallery owner Alberto Ranieri (Umberto Raho, of The Cat o’ Nine Tails and The Flower with the Deadly Sting). The bad news is that Dalmas spends pretty much the whole rest of the night at the police station, telling his story to Inspector Morosini over and over and over again, only to have the inspector confiscate his passport before finally releasing him. Part of the reason why Morosini doesn’t want Dalmas leaving the country (which he was planning on doing the day after tomorrow) is because the detective isn’t totally convinced yet that he shouldn’t consider Sam a suspect in the attack on Mrs. Ranieri. But mostly it’s because Morosini thinks there may be a connection between the stabbing at the gallery and those unsolved murders he was already working on. That effectively quadruples the writer’s potential value as a witness, even before considering Sam’s admission that there’s some important detail of the incident that he’s forgetting— something he noticed on a subliminal level, but can’t consciously recall. Morosini is hoping the detail in question concerns the assailant’s face, and he’s determined to keep the writer in Naples until he can drag more and better evidence out of him.

The inspector clearly isn’t the only one, either, who appreciates Sam’s importance to the case. Walking back for the second time toward the apartment he rents with his girlfriend, Julia (Suzy Kendall, of Torso and Assault), Sam is attacked with a meat cleaver by someone dressed exactly like the person who stabbed Monica. He’s just lucky the killer (assuming it is the same killer who took out Sandra Roversi and her predecessors) is having an off night. Sam’s assailant misses with the initial swing, and withdraws into the fog rather than press the attack once Dalmas is on his guard. Again, though, Sam doesn’t get a good look at the fucker’s face.

The attempt on his life gives Dalmas something of an attitude adjustment. Whereas he left the police station mainly just grumpy about being kept on ice as a material witness, having a meat cleaver swung at his head gives him a real personal motivation to help crack the case in any way he can. Julia gets onboard, too, once Sam explains to her what kept him out so late. She acts mainly as a research assistant, poring through back-issues of all the Neapolitan newspapers to bring Sam up to speed on the murders already committed. Thanks to her, Dalmas soon knows not only the victims’ names, but also sufficient biographical information on them to suggest who among the living might be worth an interview or two. Obviously Sam talks to the Ranieris as soon as Monica is released from the hospital. Then he goes to the antique shop where the first victim worked, the proprietor of which (Werner Peters, from Angels of Terror and The Cabinet of Horror) offers what may or may not qualify as a clue: the last thing the dead woman did was to sell a painting depicting a rustic scene in which a girl was savaged in the middle of a snowy field. Dalmas even manages to finagle the loan of a large-scale black-and-white print of the picture in question, so that he and Julia can study it at their leisure. The importance of the painting is confirmed (for us, if not for any of the movie’s characters) when we see it hanging up in the Black Glover’s lair soon thereafter, as the killer is gearing up to strike again.

It’s shortly after the fourth victim (Rosita Torosh, of Eye in the Labyrinth and Flesh for Frankenstein) is killed that Morosini unexpectedly drops in on Sam and Julia to return the writer’s passport. But even now that he can leave Naples, Dalmas is determined to see the investigation through at least to the point of identifying a plausible suspect. That eagerness to help no doubt goes some way toward explaining how easy he finds it to arrange a meeting with his next interview subject, an incarcerated pimp called Garullo (Gildo di Marco, from Four Flies on Gray Velvet and Branca Leone at the Crusades). The second victim worked for Garullo, and Dalmas is hoping the pimp will be willing to tell him things about her clients that he wouldn’t share with a cop. As it happens, though, Garullo would have been happy to talk all along, if only he knew anything useful. The one idea he can contribute that hadn’t already occurred to Sam is that if his girl got cut up by one of her johns, then the man in question can only have been a “gentleman.” She’d have had her guard up too high with the kind of lout who usually engaged her services.

Matters suddenly begin moving very swiftly after Morosini gives a press conference to reassure the increasingly skittish public. First, someone claiming to be the killer calls the police department to taunt the inspector, promising a fifth murder by the end of the week. Then Dalmas is attacked by a scar-faced gunman (Reggie Nalder, from The Dead Don’t Die and Dracula Sucks), who runs down his police escort with his car before getting out to chase the writer through what feels like half the city, and finally vanishes into the crowd at— get this— a convention for prize-fighters once Dalmas evades him long enough to raise an unacceptably high risk of drawing attention. The threatened fifth slaying is the most brutal yet, the victim (Transplant’s Karen Valenti) carved up with a straight razor in a sequence that Brian De Palma definitely saw at some point before making Dressed to Kill. And Dalmas gets a menacing phone call of his own, warning of dire repercussions for Julia if he doesn’t abandon his amateur sleuthing.

Taken together, though, all those incidents yield something that neither Dalmas nor Morosini had ever managed to discover before— a clear pattern of evidence. The gunman’s methodology differed so starkly from the slasher’s that they almost have to be two different people. Oscilloscopic analysis of the wiretap recordings reveals that Morosini’s and Dalmas’s telephone pests were two different people as well. Everyone actually in the film is unaccountably slow to process the implications, but it should be obvious by now to any attentive viewer that the increasingly unhinged Black Glover has a saner but less effectual accomplice attempting to thwart the investigation, and that the latter is somehow or other in a position to monitor what the detectives, both amateur and professional, are doing. Meanwhile, three brand new leads come to light. Garullo puts Sam in touch with a lowlife named Faiena (Pino Patti, of Burnt by a Scalding Passion and Forbidden Decameron), whose underworld connections implicate a boxer-turned-hit man called Needles as a likely suspect for the assassination attempt on Dalmas. The antique dealer comes through again by giving Sam the name and address of Berto Consalvi (Mario Adorf, from Ten Little Indians and What Have They Done to Your Daughters?), the artist who painted the unsettling picture, and who might therefore be able to shed some light on its possible connection to the crimes. And strangest but most tantalizing of all, the tape of the phone call threatening Julia is marred by a harsh clacking sound, seemingly originating at the caller’s end of the line. If that noise could be identified, it might go some way toward pinning down the whereabouts of either the killer or the killer’s accomplice. Of course, this is a Dario Argento giallo, so don’t go expecting Dalmas, or still less Morosini, to get it right on the first try.

For better and for worse, the defining features of Dario Argento’s work as a director of thrillers and horror movies are nearly all on display already in The Bird with the Crystal Plumage— most of them in something surprisingly close to their mature forms. To begin at the absolute beginning, Argento’s directorial debut offers the first of his famously enigmatic titles. This one is a poetic description of one of the major clues, establishing a pattern not only for Argento’s next two films, but for a large fraction of the me-too gialli to come. That said, there’s something slightly off about this particular instance, in that the clue referenced in the title points not to the resolution of the mystery, but to the final and most distracting red herring; the painting from the antique shop turns out to have been the key to everything all along.

Moving on now from first to most conspicuous, Argento’s visual signature is strongly apparent in The Bird with the Crystal Plumage, to a degree that I can’t recall seeing in any other debut feature except for Sam Raimi’s The Evil Dead. The inventive widescreen framing, the painterly use of color and shadow, the strategic deployment of sudden, jagged camera movements— they’re all here. So too is my favorite Argento trick, his deft toggling between blandly naturalistic compositions and highly stylized ones to signal the presence of madness and evil. For an especially instructive example, compare the sequence in which Needles stalks Sam through the streets of Naples to any of the slasher murders. The former could have come out of any sufficiently competent crime movie, but the latter are always shot so as to suggest some unwholesome, ineffable distortion of ordinary reality. Without coming right out and saying so, Argento is not merely informing us that gunman and slasher are two different people, but also telling us something about each of them. Needles is a garden variety thug who does violence for money, but the Black Glover inhabits a warped and terrible world of his or her own— a world which the victims are made to share in the moments before they die.

Then there’s the music. Goblin wouldn’t get together for two more years yet when this movie was in the works (and wouldn’t adopt that name for another three), so The Bird with the Crystal Plumage inevitably sounds rather different from Deep Red, Suspiria, or Argento’s recut of Dawn of the Dead. But Ennio Morricone could be pretty fucking weird himself when a filmmaker wanted him to, and his Bird with the Crystal Plumage score ranks among his more gonzo efforts. Its moods range from “gift-shopping montage from a Christmas movie set in Hell” to “music box found in a spooky attic having a psychotic break” to “what if the Turtles had been dropped on their heads a lot when they were babies?” Fitting accompaniment to a film about homicidal lunacy.

One more feature of The Bird with the Crystal Plumage that would recur throughout the remainder of Argento’s gialli is more easily missed— not least because the films’ American distributors would so often be at pains to remove it as completely as possible in the interest of tighter pacing and tonal unity. In their uncut versions, though, Argento’s thrillers are notable for their surprisingly zany sense of humor. Here that sense of humor is mainly embodied in the people whom Dalmas interviews for insight into the killer’s possible motives, who add up to a veritable freakshow of picturesque eccentricities. The antique dealer is an aging homosexual straight out of a lazy 70’s Britcom. Garullo belies his name by speaking with a severe stutter, which he can control only by interjecting “So long!” whenever it starts to get the better of him. Faiena invariably refuses to do anything he is asked, told, or invited to do, only to do it anyway immediately thereafter. And Berto Consalvi lives in what initially appears to be the boarded-up ruin of a farmhouse, with no means of ingress but a ladder which he drops from the windows of the second floor in the unlikely event that he deems one of his infrequent visitors worth talking to. The artist also keeps a cat coop in his loft the way non-loonies might keep a chicken coop in the yard, and for essentially the same reason. It’s a bit much in aggregate, but most of these weirdos are indeed quite funny on an individual basis.

Think of all that as the upside. The downside is that The Bird with the Crystal Plumage also marks the first go-round for what would become Argento’s most annoying storytelling tics. If any clue is susceptible to more than one reading, an Argento hero is guaranteed to arrive at the correct one only after haring off down some time-spinning narrative cul-de-sac, no matter how unlikely, illogical, or downright preposterous his initial interpretation of the evidence might be. Furthermore, an extreme case of that phenomenon is apt to occur at approximately the 90-minute mark, setting up a bid to mislead the audience toward a solution to the mystery that would be at best unsatisfyingly random, and at worst patently impossible in light of what we’ve already seen. Female love-interest characters will generally be useless and insufferable, police will be implausibly content to outsource the detective work to unqualified witnesses, and criminals’ motivations will bear little if any scrutiny. Fortunately, The Bird with the Crystal Plumage gets away with this stuff better than its successors, partly because it was the beginning of the pattern, and partly because its specific examples of these defects are legitimately less severe. Whatever damnfool thing Dalmas mistakenly makes of the clues at first, the majority of them genuinely do mean something with recognizable bearing on the case. The pre-climactic red herring is no less plausible a suspect than any other character would have been, and turns out actually to have committed a fair number of crimes throughout the story— just not any of the three stalk-and-slash murders that got the plot rolling in the first place. Julia is not so much useless as incapable of functioning under pressure, and unlike, say, Deep Red’s Gianna Brezzi, her mere presence never made me feel like my tinnitus was acting up. Inspector Morosini is at least a significant enough presence in the film to suggest that he must be doing something, somewhere in the background, even if Dalmas is the one who makes all the breakthroughs and Julia is the one who alerts the police that the endgame is playing out. All in all, The Bird with the Crystal Plumage succeeds in functioning as a mystery to a much greater extent than any of Argento’s later thrillers, which mainly just go through the motions of the genre in between their horridly high-concept murder scenes.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact