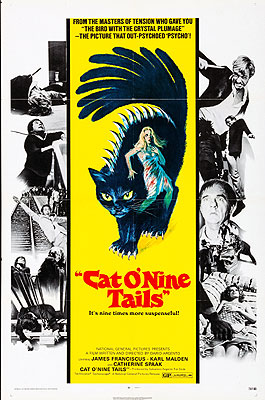

The Cat o’ Nine Tails / Operation Murder / Il Gatto a Nove Code (1971) **

The Cat o’ Nine Tails / Operation Murder / Il Gatto a Nove Code (1971) **

I used to think people were reaching a little when they called Dario Argento “the Italian Hitchcock.” I saw what they were getting at, to be sure, but it seemed to me that the comparison owed less to any actual similarities between the two directors’ bodies of work than to the kind of commentator most apt to make it simply having insufficient points of reference for suspenseful movies punctuated by garish murders. For example, Alfred Hitchcock never made anything slightly resembling Suspiria, Creepers, or Argento’s screwball take on The Phantom of the Opera, and while it wouldn’t be unfair to describe The Bird with the Crystal Plumage or Deep Red as the setup to Rear Window creating a framework for several successive riffs on the Psycho shower scene, Psycho itself wasn’t exactly typical of Hitchcock, either. It turns out, though, that Argento did make at least one movie that lands extremely close to the Hitchcock norm in terms of premise, plot, attitude, and technique. Indeed, The Cat o’ Nine Tails is so much more like a Hitchcock conspiracy thriller than a giallo as I generally understand the term that it took me a while to decide whether I ought to review it at all. I mean, if I wouldn’t review North by Northwest or The Man who Knew Too Much, then there’s no obvious reason for me to write up a movie in essentially the same tradition merely because it ladles on some gore and hides one of its clues inside a mausoleum in a spooky cemetery. In the end, though, I decided that a review of The Cat o’ Nine Tails was in order precisely because it demonstrates how far a giallo could occasionally be pushed outside of the genre’s usual comfort zone in between the German Krimis of the 1960’s and the American slasher films of the 1980’s.

The weird crime from which The Cat o’ Nine Tails proceeds is not a grisly murder, but a break-in at a medical research laboratory called the Terzi Institute. In the dead of night, somebody cold-cocks the guard at the gatehouse, jimmies a window, and picks the lock on the office of Dr. Calabresi (Carlo Alighiero, from Torso and Next!). The criminal is observed by three people, none of them in a position to do anything about it. A staff member working late finds the injured guard and catches a fleeting glimpse of the culprit fleeing the scene; it is he who raises the alarm and summons the police. But what will turn out to be the more important sighting was made before the break-in even occurred, when a blinded ex-reporter named Franco Arno (Karl Malden, from Phantom of the Rue Morgue and Meteor) was out for a walk with his pre-teen foster-daughter, Lori (Cinzia di Carolis, of Lust and Cannibal Apocalypse). Shortly before the incident at the lab, the pair happened to pass by two men sitting in a car, discussing blackmail. They probably figured no one would be able to hear them, what with the doors closed and the windows up, but you know how it is with blind people in movies. Arno made a point of stopping to tie his shoe while he was still within earshot, and asked Lori to make a note of the men’s faces while he did so. One was too deep in shadow to be visible as more than a silhouette, but the girl was able to commit his companion’s face to memory as instructed. Then a bit later, from his apartment overlooking the Terzi Institute, Arno heard both the altercation at the gatehouse and the break-in itself.

The only thing taken from the institute that night was a document housed in one of Calabresi’s filing cabinets, in a drawer marked “Genetics.” It must not have been an important paper for the day-to-day running of the lab, however, because neither institute boss Professor Fulvio Terzi (Tino Carraro, from Paranoia and The Legend of the Wolf Woman) nor any of his subordinates notice its absence while searching the building for signs of theft the next day. Indeed, Terzi goes so far as to tell the press, the district attorney, and Superintendent Spimi (Pier Paolo Capponi, of Seven Bloodstained Orchids and The 10th Victim), the detective leading the police investigation, that nothing was stolen whatsoever. Dr. Casoni (Aldo Reggiani, from Young Lucrezia and The Sex Machine), the youngest scientist among the institute’s senior staff, suggests industrial espionage as an explanation for the incident, but Terzi himself is weirdly insistent that no such thing is possible. In point of fact, though, there is one man who recognizes that something was taken, knows exactly what it was, and thinks he has a pretty good idea who made off with it and why— Dr. Calabresi. Hey, it was his filing cabinet, after all. But Calabresi doesn’t tell Terzi or the police what he has discovered, and even goes so far as to swear his fiancée, Bianca Merusi (Rada Rassimov, of Lifesize and Baron Blood), to secrecy. All he says by way of explanation is that this could mean a big step forward for him. If that sounds like a blackmail plot in the making, well, it just so happens that Calabresi was one of the men whom Arno overheard talking in that parked car last night. He doesn’t live to put his plans into motion, however. That very evening, at the start of his homeward commute, somebody— and clearly somebody Calabresi knows, at that— pushes him from the rail station platform into the path of his own arriving train.

By a freak coincidence, though, that platform was crawling with reporters at the time, for one of the fatal train’s inbound passengers was some B-list celebrity of the sort whose presence is always a magnet for bottom-feeding journalists. What’s more, a photographer called Righetto (Vittorio Congia, of A Completely Naked Horse and When Men Carried Clubs and Women Played Ding Dong) happened to take a shot of the train at the exact moment when Calabresi was hurled in front of it. The killer was hidden from Righetto’s view at the time by one of the pillars supporting the roof over the platform, so the photographer assumed Calabresi’s fall was just an accident. But even without recognizing the murder for what it was, both Righetto and his reporter partner, Carlo Giordani (James Franciscus, from Nightkill and Butterfly), are quick to realize that they’ve stumbled onto a much better story than the one they were sent to cover— especially since both men were at the Terzi institute earlier, and remember Calabresi as one of the researchers there.

The gruesome death at the train station is above-the-fold, front-page news, naturally. Franco Arno may no longer be able to read newspapers, but since his morning routine includes having Lori read them aloud to him over breakfast, he learns about Calabresi’s fate quickly enough. And because a headshot of the scientist in happier times is printed as an insert along with the lurid photo of his demise, Lori is in a position to recognize him from their encounter on the street the night before last. Word that someone whom he heard talking blackmail died in a bizarre accident less than 24 hours later gets Arno’s long-dormant reporter’s instincts buzzing, and right after breakfast, he and Lori head over to the paper’s offices to meet with Carlo Giordani. Rather than tell Giordani everything he suspects, however, Arno leads with a question about the photo of Calabresi falling in front of the train: was it cropped, or does the version on the front page show the full frame? A quick phone call to Righetto not only establishes that it was cropped, but leads to the discovery of a vital yet easily missed detail in the contact print showing the complete image. There’s a hand reaching out from behind a pillar near the edge of the frame, and damned if it doesn’t look like it just gave the doomed scientist a shove! Alas, it seems that Calabresi’s killer subscribes to the same morning newspaper as Arno, and had much the same thought upon seeing today’s front page. By the time Giordani, Arno, and Lori reach the pressing plant where Righetto has his film lab, the photographer has been garroted to death, and all negatives and prints of the incriminating picture are gone.

Of course you realize a situation like this is catnip for a newshound like Giordani, even before factoring in the personal connection that the latest victim was a friend of his. And that goes for retired newshounds like Arno, too. So while Superintendent Spimi plods his way through the case in an official capacity, the two reporters mount their own parallel investigation, pursuing a somewhat arbitrary total of nine leads tallied so as to justify the movie’s title. A more narrative-focused organizational scheme yields just five likely theories of the case, however. In keeping with Casoni’s industrial espionage suggestion, the crimes at and around the Terzi Institute might have something to do with the broad-spectrum wonder-drug the lab is trying to develop, which promises to revolutionize medicine in a manner comparable to the advent of antibiotics a generation before. Or maybe they concern the institute’s other major line of research, exploring the supposed link between propensity toward criminal behavior and the form of sex-chromosome trisomy colloquially known as supermale syndrome. Then again, there could also be a more sordidly personal explanation for the document theft, the attempted extortion, and the ensuing murders. In that case, perhaps we should be looking at Dr. Esson (Tom Felleghy, from The Wonders of Aladdin and Four Flies on Grey Velvet) and his ongoing campaign to take Terzi’s daughter, Anna (Catherine Spaak, of The Libertine and The Story of a Cloistered Nun), as his mistress. Then there’s Dr. Braun (Horst Frank, from The Dead Are Alive! and The Vengeance of Fu Manchu), a wealthy old poof whose current boy-toy (Werner Pocanth, of Devil Hunter and A Man Called Rage) has a similarly aging and well-heeled ex (Umberto Raho, from Women in Cell Block 7 and The Eerie Midnight Horror Show) who wouldn’t scruple at much to get him back. Maybe he’d go so far as to commit a series of escalating crimes for which to frame Braun in the hope of taking his rival out of the picture? By far the most twisted and blackmail-worthy personal life among this bunch is that of Terzi himself, however. He adopted Anna from an orphanage at an age when she was old enough to understand exactly what that did and did not mean, and the pair have been maintaining a necessarily furtive but mutually agreeable sexual relationship ever since Anna was a teenager. And finally, just because this is at least marginally a giallo, I suppose we ought to brace ourselves for a sixth, bonus possibility— that the truth behind it all will turn out to be some utterly bogus bullshit that accounts for none of the evidence actually presented, and makes no fucking sense whatsoever. But one thing is clear, regardless of who broke into the Terzi Institute that night or why. The culprit, whoever they may be, is prepared to kill anyone who might know or learn enough to expose them. That includes Bianca Merusi, any and all non-culpable members of the institute staff, and most of all the two meddling reporters. And as Arno soon discovers, it could even include Lori, should the killer decide that such extreme measures are necessary to make him and Giordani back off.

This is not at all a kind of movie that I’m inclined to like, so it’s fair to ask to what extent my low-ish opinion of The Cat o’ Nine Tails is due to specific shortcomings on its part, and to what extent it’s just a matter of my not getting along with conspiracy thrillers as a class. I’m frankly not sure I know the answer to that myself. What I can tell you for certain is that this movie never really held my interest for more than a scene or two at a stretch, and that I spent far more of The Cat o’ Nine Tails being irritated by Dario Argento’s bad habits as a screenwriter than I did being impressed by his good ones as a director.

You may remember me grousing, in my review of The Bird with the Crystal Plumage, about Argento’s tendency to send his amateur detectives down one dead end after another, as each lead they uncover either comes up bust or gets foreclosed by an inconvenient murder before it can be exploited. In The Cat o’ Nine Tails, that happens approximately nine times (depending on how you count the one where Giordani finds the solution to the mystery staring him right in the face, but ignores it in favor of some irrelevant shiny object), which is at least five too many. You may also recall my annoyance at Argento’s addiction to the false climax, in which the protagonist decides (just in time for what you’d expect to be the end of a conventionally paced movie) that they’ve got it all figured out, only their conclusion is not merely wrong, but self-evidently stupid more often than not. The Cat o’ Nine Tails gives us a real doozey, as Giordani briefly convinces himself that Anna Terzi must have two Y chromosomes. I suppose it’s technically possible, but the other circumstances presented here would require that she also exhibit the complete form of androgen insensitivity syndrome, and at that point we’re well over the border into Not Bloody Likely.

Meanwhile, Argento’s direction here is much lower-keyed than it was in The Bird with the Crystal Plumage, or than it would be in any of the later films of his that I’ve seen. In a sense that’s a good thing, insofar as the story in The Cat o’ Nine Tails really doesn’t lend itself to the kinds of cinematographic fireworks for which its auteur is otherwise justly known. It would have been nice if Alfred Hitchcock had ever learned to dial it down like this. The trouble is, with The Cat o’ Nine Tails looking so much like a conventional thriller, it’s that much easier to notice that this movie is often as nonsensical as a typical full-on giallo. The only sequences that have any visual flair to them are the opening break-in, the killer’s grisly fate, the aforementioned bit about stealing a clue from inside a mausoleum, and— in a refreshingly uncharacteristic touch— a high-speed car chase between Anna Terzi and a police escort that she’d like to be rid of.

The Cat o’ Nine Tails’ main redeeming feature is also wildly atypical. Nothing else in this movie is half as memorable or compelling as the relationship between Franco Arno and Lori. Arno is one of the better renditions I’ve seen of the “deceptively competent boob” school of hero, and Karl Malden plays him as sort of a cross between James Stewart in Hitchcock mode and Ray Milland at AIP. Lori, for her part, might well be the sharpest and most self-possessed heroine in the entire Argento repertoire, and although it’s difficult to get a fix on Cinzia di Carolis’s performance through the rather indifferent dubbing of her dialogue, her physical presence conveys a strong sense of a child well used to taking on an extraordinary level of responsibility for her age. Between them, they make a credible and endearing pair as people perfectly comfortable both with needing each other and with meeting each other’s needs despite their limited capacities to do so. It’s shocking how much the film loses when Lori is sidelined, first in an attempt to keep her out of danger, and later on when the killer takes her hostage.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact