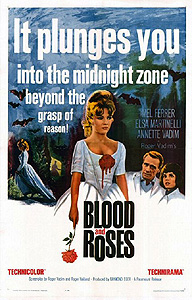

Blood and Roses/To Die of Pleasure/Et Mourir de Plasir (1960/1961) ***½

Blood and Roses/To Die of Pleasure/Et Mourir de Plasir (1960/1961) ***½

We’ve talked before about the porosity of the boundary between horror and sex movies in Continental European practice. Well, now let’s have a look at how early that phenomenon developed. It is a curious fact that in Europe, where most countries subjected the cinema to some form or degree of official national censorship, filmmakers were nevertheless often freer during the postwar years than their counterparts in America, where the movie industry had been permitted for the most part to police itself. The gradual loosening of content restrictions over the course of the 40’s, 50’s, and 60’s is a major theme of film history on both sides of the Atlantic, of course, but the western half of the European mainland was at nearly all times visibly out in front of the pack. Look to the career of Frenchman Roger Vadim for an example. These days, Vadim might be remembered less as a director than as a collector of beautiful, fair-haired women, but his dual vocations were mutually reinforcing. Most significantly, Vadim used Brigitte Bardot, the first of his notorious starlet wives, as the centerpiece of And God Created Woman in 1956. By modern standards, it would be misleading to describe And God Created Woman as a sex film, but today’s standards were not in place in the mid-1950’s— and by mid-50’s standards, that movie was smut with a capital “Oh God, yes— right there!” Much the same could be said of Vadim’s later Blood and Roses, loosely based on J. Sheridan Le Fanu’s seminal lesbian vampire story, “Carmilla.” Although nominally a horror film, Blood and Roses trades at least as much upon sex as it does upon scares or violence. In what would become increasingly recognizable over the next fifteen years as a central tradition of European macabre cinema, it is a horror movie about sex— specifically about the deadly madness into which sexual jealousy so readily devolves— spiked with hints (but by necessity only hints, this early in the game) of such salacious details as cousinly incest and sapphic eroticism.

Blood and Roses begins in what must be the least likely setting imaginable for a “Carmilla” movie, the cockpit of a DC-9 taking off from Paris and bound for Rome. Yes, this is going to be a thoroughly modernized interpretation, set some 200 years after the 1765 peasant uprising that came close to exterminating the Karnstein family. As always, the Karnsteins were reputed to be vampires, although I suspect given the circumstances of their near-demise that we’re supposed to have the Marxist sense of that term in the backs of our heads along with the literal one. Legend has it that one of the undead Karnsteins escaped the massacre, however— the young Countess Millarca. Millarca died (and came back from the dead) very shortly before the peasant revolt, and she was rescued from the mob’s fury by her cousin Ludwig, who was in love with her. Ludwig hid Millarca’s coffin, and then went into hiding himself. He’d have been better off leaving her to her fate, though, for Millarca evidently did not view the grave as a legitimate reason not to pursue their relationship further. Three times in his subsequent life, Ludwig was engaged to be married, and each time, the bride-to-be was murdered by Millarca on the eve of the wedding.

All that we learn from Carmilla Karnstein (Annette Stroyberg, who was calling herself “Annette Vadim” at the time Blood and Roses was made), the dead-ringer descendant of the legendary vampire whose name she would share if the letters were rearranged a bit. Carmilla represents the senior, Austrian branch of the family, but we will be primarily concerned with the doings of the junior branch, based in Italy. The current head of the Italian Karnsteins is Count Leopoldo (Mel Ferrer, from The Tempter and The Visitor), with whom Carmilla lived for most of her childhood and adolescence. The occasion of their reunion is Leopoldo’s impending marriage to Georgia Monteverdi (Elsa Martinelli, of The Trial and The 10th Victim), the daughter of a high-ranking judge (Marc Allégret, from a little-seen 1955 version of Lady Chatterley’s Lover). Georgia knows that Leopoldo and Carmilla were close when they were kids, and can see that they remain very fond of each other even now. Nevertheless, she sees no reason to consider the other woman a rival— after all, it was Georgia whom Leopoldo asked to marry him!

The feeling is far from mutual, however. Always inclined to be moody, Carmilla conducts herself with bad grace indeed during the days of celebration leading up to the wedding proper. It’s weird, though— the more obvious Carmilla’s jealousy of Leopoldo becomes, the fonder Georgia seems to grow of her, to the point where you have to wonder if maybe there isn’t a bit of sexual attraction at the bottom of it all. Regardless, the turning point in this three-sided relationship comes during the lavish masquerade that Leopoldo holds a bit less than a week before the nuptial date. The count had hired internationally renowned pyrotechnician Carlo Ruggeri (Alberto Bonucci) to climax his party with a suitably impressive fireworks display, and Ruggeri identified the abandoned abbey on the ridge overlooking the Karnstein villa as the best staging area for his work. It’s virtually indestructible, it’s visible all over the property, and to the best of Leopoldo’s knowledge, no one has set foot there in almost two centuries. But as it turns out, someone the count didn’t know about had made regular use of the abbey as recently as 1944. In those days, the sturdy old ruin was a Nazi ammunition dump, and untold tons of Axis bullets, mines, and artillery shells are still on the premises. Ruggeri’s fireworks set off some of those forgotten explosives, and their detonation blows a hole in the abbey’s foundation. What has that to do with Carmilla, you ask? Well, she happens to be strolling sulkily in that direction when the accident occurs (her cousin’s wedding to another woman obviously isn’t something she fells like celebrating), and she spots something curious through the newly formed rent in the ancient stonework. It’s the legendary crypt of Millarca Karnstein! Evidently old Ludwig hid Millarca not in the sense of moving her to a secret location, but rather walled her up so that no one not intimately acquainted with the layout of the abbey would be able to find her. In case I haven’t yet made this clear, Carmilla has always felt a strange identification with her lookalike anagrammatic namesake, and heedless of the danger of further explosions, she heads down at once into the tomb. Inside, Millarca’s sarcophagus stands basically intact, but with its lid jarred loose by the blast. As Carmilla approaches, that lid slides completely free, and…

And what? That’s the question around which the whole rest of the film pivots. What we can say for certain is that from that moment on, Carmilla begins keeping a weird sleep schedule trending markedly toward the nocturnal. She takes to roaming the villa’s grounds by night dressed in a gown that belonged to Millarca, so that she is mistaken for the dead countess’s ghost by Giuseppe the groundskeeper (Serge Marquand, from Barbella and The Grapes of Death). She acquires a taste for 18th-century music, and displays a hitherto unsuspected mastery of 18th-century family history. Animals of all kinds— including her own horse— start behaving strangely around her, as if her mere presence were terrifying to them. And most significantly, she murders Lisa the maid (Gaby Farinon, of Assignment Outer Space) to drink her blood, and tosses her body over a cliff to dispose of the evidence. You can imagine how the local villagers take it when a pair of teenage girls discover the corpse, no matter what verdict Dr. Valeri (The Nude Vampire’s René-Jean Chauffard) reaches in his capacity as coroner. So what does all this mean? Has Millarca killed Carmilla and taken her place? Has Carmilla been possessed by the vampire’s spirit? Or has Carmilla, never a sterling exemplar of psychological health to begin with, finally lost her marbles completely, so that she believes herself to be Millarca, back once again from the grave? Whichever it is, the implications for Leopoldo and Georgia are sure to be pretty dire.

I’m cheating a little in the foregoing synopsis. As I have described it, that’s the plot of the original Franco-Italian edit of Blood and Roses, which is currently unavailable in English-language release, and is not the version I actually watched. It’s easy enough, though, to extrapolate that story from the American version— all you have to do is to ignore the voiceovers from Millarca’s ghost that intrude constantly upon the film whenever there would otherwise be more than about ten seconds of uninterrupted silence. Those voiceovers are designed to remove all trace of ambiguity from Blood and Roses, providing a firm answer to the question of what’s wrong with Carmilla, and coming down on the side of spectral possession. Yes, it’s the old routine in which the American distributors of a foreign film assume that their audience is too stupid to understand the movie as its creators made it, and “helpfully” alter it to connect all the dots for us. Fortunately, the technique used here is so half-assed and so crudely obvious that it doesn’t much harm the picture, at least for audiences accustomed to watching through artifacts of distributor vandalism.

In any case, this is clearly not “Carmilla,” regardless of what the opening credits claim to the contrary, and those who come to Blood and Roses seeking anything resembling Le Fanu’s story will be left sorely disappointed. Most conspicuously, in this supposed adaptation of the lesbian vampire subgenre’s ur-text, Carmilla is unmistakably heterosexual— indeed, the entire plot hinges on her heterosexuality. With one exception, what few hints of lesbianism are present here flow in the opposite direction, with Georgia professing an affection for her rival which suggests that this whole sordid business could have been avoided if Leopoldo had but followed Roger Vadim’s own example, and invited the two women in his life to a menage-a-trois. (The aforementioned exception occurs toward the beginning of the third act, when Carmilla seems to kiss Georgia while they’re alone together in the greenhouse. In fact, though, this “kiss” is merely Carmilla taking the liberty of sucking the blood from a cut on the other woman’s lip.) Vadim’s Carmilla reacts to Georgia’s subtle overtures (if indeed that’s what they are) with much the same confused ambivalence as Le Fanu’s Laura displayed in the face of his Carmilla’s much more overt ones.

But while Blood and Roses is hardly a satisfactory adaptation of “Carmilla,” it nevertheless functions remarkably well as a sequel to its inspiration, and has much to recommend it for thoughtful horror fans who still appreciate the concept of vampirism, but are thoroughly sick of the two or three standard approaches to the subject. In some ways, Blood and Roses strikes me as a much-belated European response to Val Lewton’s horror movies for RKO. Like the majority of those films, Blood and Roses cloaks what is fundamentally a psychological thriller in a skin of supernatural horror, and circumvents the target audience’s natural antipathy for “rational” explanations by making the validity of the supernatural manifestations the story’s central mystery. Obviously, that demands from Vadim and his collaborators a much more acute understanding of people’s mental and emotional processes than was typically displayed by horror filmmakers in this era, together with a far greater investment in character development. At a time when most fright films were simplistic stories of good vs. evil, Blood and Roses presents a startlingly mature examination of sexual neurosis and the dark side of exactly the sort of romanticism in which escapist cinema normally trades. It also recalls the best of the Lewton horrors in the emphasis that Vadim places on imagery and atmospherics. Indeed, Vadim carries that approach farther than Lewton-employed directors like Jacques Tourneur or Robert Wise ever did, frequently injecting openly subjective sequences that play like Vampyr by way of The Tingler (or maybe vice versa). The best example of the latter is Carmilla’s climactic attack on Georgia, which is portrayed almost solely via the dreams it provokes from the sleeping victim’s subconscious. Blood and Roses was ahead of a whole lot of curves, and it’s a mystery to me how it could have sunk into such obscurity as envelops it today.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact