The Nude Vampire / La Vampire Nue (1970) -**½

The Nude Vampire / La Vampire Nue (1970) -**½

This is how you get typecast as a director. When Jean Rollin’s debut feature, The Rape of the Vampire, hit theaters in May of 1968, it was almost literally the only game in town for would-be cinema-goers. Throughout that month, all of France was wracked by riots and general strikes in opposition to the policies of the Charles de Gaulle government. The protestors just about shut down the whole French economy, one minor result of which was that The Rape of the Vampire was one of just two new movies to come out in the entire country during the week of its premiere. Apparently just about everyone who was not actively occupying a factory, marching in the streets, or clashing with the police went to see it, and although reactions were almost uniformly negative, the film made a ton of money and established Rollin as someone to watch out for. The next time he wanted to make a movie, it was all but inevitable that his backers would say, “Can you give us another one like that last one?” forgetting the extraordinary circumstances behind the previous picture’s success. Thus The Rape of the Vampire was followed by The Nude Vampire, which was followed by The Shiver of the Vampires, which was followed by Requiem for a Vampire. Now Rollin is forever the Sexy Vampire Movie Guy, even though he finally said enough was enough after Lips of Blood in 1975, and didn’t take up the subject again until Two Orphan Vampires twenty years later. It must have been doubly frustrating for Rollin, since even one of his vampire movies isn’t really a vampire movie. For that matter, The Nude Vampire’s title character isn’t nude, either, but I don’t suppose The Diaphanously Veiled Mutant whom Everybody Ignorantly Mistakes for a Vampire would fit on the average theater marquee.

Pierre Radamanthe (Rollin’s brother, Olivier, who also appeared in The Rape of the Vampire and The Grapes of Death) is out for a late-night walk when he encounters a beautiful girl in a transparent orange dress (Caroline Cartier), who is being pursued by people in strange animal-head masks that somewhat anticipate the villagers’ May Day costumes in The Wicker Man. The girl implores Pierre’s aid, but his efforts to sneak her to safety are not long successful. The pair find themselves trapped on a footbridge with masked assailants at either end, and the girl is shot dead. Curiously, the killers pay no heed to Pierre after that. They just pick up the girl’s body, and carry it to a wall-encircled mansion not far away. Pierre is rather shocked to realize that he knows the place— it’s the headquarters of the secret club presided over by his father! Although Pierre is unable to sneak in on this occasion to spy on the surely sinister doings at the club, he determines to get to the bottom of the mystery.

Georges Radamanthe (Maurice Lemaitre) is an industrialist of some kind, and like a lot of very rich men, he is extremely eccentric. One look at the livery in which he dresses his twin maids (Catherine and Marie-Pierre Castel, who are similarly paired in Introductions and Lips of Blood) should be enough to tell you that. He spends most of the time when we can see him palling around with two more wealthy weirdos, Fredor (Jean Aron) and Voringe (Bernard Musson, from Erotic Journal of a Lady from Thailand and the 1964 version of Fantomas), who are both members of his club and collaborators on some hush-hush project that is probably based at the mansion. Georges has absolutely forbidden Pierre’s presence at the club, and he is furious when he learns from the doorman that the lad attempted to get in tonight. If Pierre is going to learn what goes on in there, it certainly won’t be by asking his dad.

Pierre turns to his friend, Robert (Pascal Fardoulis), for assistance. I’m not sure what help he thinks an erotic painter is going to provide him, but I guess he has to have somebody’s aid. In fact, though, all Robert ever really accomplishes is to draw sufficient attention to himself to merit assassination by the elder Radamanthe’s secretary, Solange (Ursule Pauly, of Dirty Lovers and Death Disturbs). Pierre himself has better luck on his next attempt to infiltrate the club. After waylaying one of the legitimate guests, he uses that guest’s invitation card to bluff his way past the club’s whole security apparatus. What he witnesses as a consequence exceeds even his wildest speculations. This “club” of his father’s is really a bizarre suicide cult that worships the girl he met the other night. What’s more, the object of their adoration is alive and well, despite having unmistakably been shot to death on that same evening. Pierre has no idea what to make of it, but he recognizes at once that he knows enough now to extort the full story from his dad.

Alright, alright— Pierre wants the full story? Well, here it is. The girl in orange is a vampire. When the elder Radamanthe and his colleagues learned of her and her worshippers, they created the club as a pretext for bringing the whole weird business under their control. Georges’s object was to study the girl, to see if he could discover the biological mechanism of her immortality. So far, they’ve had no success— and now thanks to Pierre, they’re going to have to shift their operation to a new secret hideout. Luckily, arrangements were already being made for the move on a prophylactic basis, and Georges has no intention of telling his son where the new site is going to be. After all, the whole point of moving is to escape the reach of his blackmail.

Georges, Fredor, and Voringe don’t realize, though, that the nobleman who’s agreed to lend them his chateau (Michel Delahaye, from Alphaville and The Shiver of the Vampires) is pursuing an agenda of his own. Pierre finds that out first, when one of the nobleman’s agents (Ly Lestrong) sees to it that he learns where his father and the others are taking the supposed vampire. The younger Radamanthe doesn’t believe for one second that the girl in orange is anything but an ordinary human who has fallen into the clutches of madmen, and he remains determined to rescue her from his father and the cult. The nobleman and his followers— which is apparently to say everyone who lives on his estate— have much the same objective, but a somewhat different understanding of what that means. You see, although Pierre is right that the girl in orange is no vampire, his father is equally right about her being no normal person, either. Like the nobleman and his tenants, she is one of a small group of mutants who represent the next phase of human evolution. The nobleman has concluded that these mutants will never be safe until humanity as a whole catches up to their level of development, and he’s probably right if we ignore the niggling little detail that evolution doesn’t work that way. That’s why he bought this particular chateau. Somewhere on the property is a passageway to another dimension, where the mutants can hide out until Earth becomes a less inimical environment for them. The mutants are counting on Pierre to rescue the girl in orange while they besiege the chateau, keeping Georges, his colleagues, and the cult occupied.

The Nude Vampire is closer in spirit to The Rape of the Vampire’s ridiculous second half than to the laudable, haunting first, but this movie is rather more enjoyable than its predecessor on the whole, because it picks a tone and stays with it. That tone, for the record, is “You’ve got to be fucking kidding!” It was Rollin’s intention that The Nude Vampire should embody the idea of mystery— not simply that its plot revolve around solving one, but that every aspect of the film be baffling and enigmatic. He certainly succeeded in keeping me perplexed, so mission accomplished, I guess. Obviously a lot of movies spend their first acts piling up one inexplicable thing after another, but The Nude Vampire persists in that mode right up to the end. Very little gets explained along the way, and what interim answers we do get usually make things more confusing, since they don’t add up with what we’ve already seen. Furthermore, notice that the most comprehensive and detailed explanation offered before the conclusion— the one that Pierre blackmails out of his father— ends up being incorrect, even though Georges (a character whom we’d expect to know what he’s talking about) is telling what he believes to be the truth. And of course the full story given at the last by the mutant leader is so nonsensical, and so thoroughly at odds with the kind of movie we thought we’d been watching, that even it doesn’t really lessen our bewilderment. The danger of this approach is that it depends heavily upon the audience understanding the creator’s aims up front. A movie that succeeds in being totally opaque and mystifying is largely indistinguishable in practice from one that utterly fails at telling a more conventional sort of story— and because the experience of watching the two types of film is essentially the same, the difference is arguably artificial and immaterial in the first place.

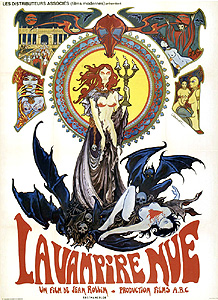

The Nude Vampire was Rollin’s first movie shot in color, and the change in film stock has an enormous impact on how Rollin’s vision comes across. The cheap imitation of sumptuous visual lunacy that became his trademark hereafter simply was not possible in black and white, although seeing The Nude Vampire does retroactively suggest how the second half of The Rape of the Vampire was meant to look. While I normally think of Rollin as Jesus Franco’s closest kindred spirit, his devotion to kitsch finery on five dollars a day ties him as well to Andy Milligan, whose training as a tailor led him to try counterfeiting a standard of costuming and set-dressing that any reasonable calculation would have placed beyond his means. The Rape of the Vampire’s Queen of the Vampires may have been the prototype for the Rollin look (best summed up by something I exclaimed upon first seeing Georges Radamanthe’s twin maids: “What in the hell are the women in this movie wearing?!?!”), but The Nude Vampire is where we first see it in full flower. Perhaps significantly, this was also Rollin’s first collaboration with cinematographer Jean-Jacques Renon. The two men would work together several times over the next six years, their partnership encompassing some of Rollin’s most stylistically important pictures: The Shiver of the Vampires, The Demoniacs, The Iron Rose. This isn’t a case, though, where one cameraman understands a director like nobody else, for Rollin was able to get similar results from Renan Polles and Jean-François Robin, among others. I don’t know whether that means Rollin knew exactly what he wanted almost from the beginning, and had a rare knack for communicating his desires, or whether it means that he absorbed from Renon some technical know-how that enabled him to talk shop with other cinematographers at an unusually high level. In any case, Rollin’s post-Renon movies don’t seem to suffer a drop-off in visual quality like what happened to Lucio Fulci after he and Sergio Salvati parted ways. The esthetic that first came together in The Nude Vampire would remain in more or less full effect until the end of Rollin’s career.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact