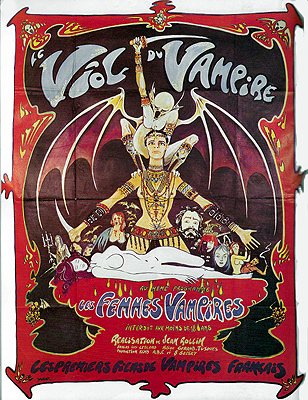

The Rape of the Vampire / Queen of the Vampires / Le Viol du Vampire (1968) **

The Rape of the Vampire / Queen of the Vampires / Le Viol du Vampire (1968) **

When Jesus Franco died earlier this year, the obituaries were more or less unanimous on the point that however one judged the merits of his work, one had to admit that there was never anyone else like him. That wasn’t exactly true, though. For over 40 years, there had been one other filmmaker whose movies were frequently very much like Franco’s— in tone, in subject matter, in fearless disregard for quality or commerciality as those terms are usually understood by mainstream audiences— and who shared Franco’s curious combination of obscurity and notoriety, utterly unknown to the great majority of cinema-goers, yet renowned among lovers of the weird who might nevertheless have seen only a tiny fraction of his output. That “other Franco” was a Frenchman by the name of Jean Rollin, and we’re long overdue for a look at him.

Rollin’s career was more broadly varied than his reputation, which rests mainly on a string of sexy, surreal vampire movies that he directed throughout the late 60’s and early 70’s, when censorship of the arts in France was in a state of rout and all the creative media were coming increasingly to represent the fever-dreams of a nation in turmoil. He never set out to be a horror director or a pornographer; it was simply that horror and sex movies offered a degree of freedom that could be had in no other genre, while costing next to nothing and turning a reliable profit. As for vampires specifically, that part was almost pure accident. Jean Lavie, an acquaintance of Rollin’s who worked in film distribution, had picked up the import rights to Dead Men Walk, which apparently hadn’t made its way to France at any point during the quarter-century since its creation. What Lavie hadn’t realized was that the movie was only a tad more than an hour long— perfectly acceptable for a second feature in 1943, but an invitation to customer rebellion as a stand-alone attraction in 1968. He was going to need a half-hour or so of additional content to make the property viable at the box office, perhaps a short film in a similar vein. Rollin had been making shorts for several years by that point, and he volunteered to come up with something Lavie could use. Of course, the first thing Rollin would need was money, for which he turned to another industry contact, geologist-turned-producer Samuel Selsky. Selsky scraped together 100,000 francs (equivalent to perhaps $25,000 in those days), and The Rape of the Vampire was born.

That’s where matters took a turn for the bizarre. The Rape of the Vampire ran a little long by the time Rollin had it edited to his satisfaction, close to 45 minutes. More importantly, it was a much better movie than Dead Men Walk, in virtually every way. Selsky thought it deserved more than a toss-off release as a supporting feature, and suggested that Rollin expand it to full length. (Incidentally, I never did figure out what Lavie ended up using as a co-feature once The Rape of the Vampire outgrew its original purpose.) Probably Selsky imagined that Rollin would shoot new scenes to interpolate throughout the film, adding a subplot here, fleshing out a character relationship there, and so forth. That’s not what Rollin did, though. Instead, he shot a whole second mini-movie, entitled The Vampire Women, and tacked it onto the end. Thus when The Rape of the Vampire appeared in theaters in May of 1968, it was in effect its own sequel. Even stranger, The Vampire Women bore no resemblance to the original short, even though it concerned most of the same characters— who had to be brought back to life for the story to continue, because The Rape of the Vampire ended with the near-total extermination of its cast! Whereas The Rape of the Vampire is a psychology-driven mood piece that plays almost like Martin’s extremely French country cousin, The Vampire Women is an abysmally stupid and incoherent Eurospy movie in which all of the characters save one are either vampires or Renfields.

In an old chateau near Dieppe (it seems like all of Rollin’s movies end up near Dieppe at some point) live four strange sisters. (I’ve had a hell of a time figuring out who plays whom in this movie. One of the sisters is definitely Nicole Romain, and another is certainly Ursule Pauly, from The Nude Vampire and Beyond Love and Evil, but the others I’m not so sure about. Part of the problem is that there aren’t enough women with the appropriate level of billing in the credits to account for all the major female characters.) They might be vampires— at least they and the local villagers all think so. The thing is, they don’t act like vampires, or at any rate not consistently. Only one of them fears the sunlight, for instance, although all claim that they would be destroyed if they ever saw it, even as they habitually go about the castle’s grounds at midday. Another claims to have been violently blinded by a mob from the village at the turn of the century, but we can plainly see that there’s nothing physically wrong with her eyes. Most tellingly, only one of the girls drinks blood, and she only from birds. So either these chicks are not vampires at all, or else vampirism doesn’t mean what we usually think it means. Where, then, did this mass delusion get started? My money is on the lord of the manor, who works assiduously to keep the sisters and the villagers in terror of each other, for reasons known only to himself.

Then one day, a trio of Parisians show up. One of them, Thomas (Bernard Letrou), is a psychiatrist who has heard about the sisters, and hopes to cure them of what he assumes to be their madness. The others are Thomas’s friend, Mark (Marquis Polho), and Mark’s wife, Brigitte. (And here we have another credit quandary. Most online sources agree that this is Solange Pradel, of World on a Wire and From Ear to Ear. However, in a database of French actresses that I’ve otherwise found invaluable for solving such mysteries, Pradel’s name appears with a photo of the light-phobic “vampire,” while Brigitte’s image illustrates the name of Catherine Deville. So I just don’t know at this point, and probably won’t until I see one of Pradel’s other films.) Mark is suspicious of this whole undertaking. He harbors an almost superstitious dread of insanity, which he does not believe can ever be truly cured. So far as Mark is concerned, the thing to do with lunatics is to lock them in an asylum, and throw away the key. Nevertheless, Thomas does quickly seem to start having a positive effect on his patients— altogether too much so for the seigneur’s liking, in fact. When Thomas uproots and burns all the crosses that the villagers put up around the chateau to seal the vampires inside, the lord of the manor goes into town to tell everyone that the outsiders have set the monsters free. An angry mob is an unreliable instrument, however, and if the old man was trying to put things back the way they were, he chose exactly the wrong approach. The only survivors of the villagers’ attack are Mark (who joins the mob after Brigitte is killed, not realizing that it was they who killed her) and the lord himself.

That’s where the story originally ended. Now, though, the last of the fighting is followed by the arrival of the Queen of the Vampires (Jacqueline Sieger) and her entourage. So evidently vampires are real after all. The Queen has the landlord executed for his failure to protect the sisters, who were vital to her master plan— whatever that is. She also orders all the evidence of vampire activity in the area destroyed, which includes burning all the bodies. That last directive proves unexpectedly difficult to carry out. For one thing, Mark has already left the village with Brigitte’s corpse, intending to have it decently buried in Paris. For another, the hysterically blind sister survived the mob’s attack after all (although she’s blind for real now), and the Queen’s agents don’t know where she’s hiding. And weirdly enough, the vampire women charged with cremating Thomas and his most recalcitrant patient among the sisters disobey orders, and leave them on the beach in such a way that they can be revitalized by the landlord’s spilled blood. Thomas still seeks a cure when he returns to life, although he obviously has a somewhat different understanding now of what that means. Mark, meanwhile, is more determined than ever to kill any vampire that crosses his path— which puts him in a difficult position when the vampires resurrect Brigitte as one of their own to use as a spy against him. The vampires turn out to have a medical research laboratory for who the hell knows what reason, but the doctors there (Eric Yan— I think— and Ariane Sapriel) are in no sense loyal to the Queen. Transformed like Thomas against their will, they too toil in secret over a cure for their condition instead of doing whatever it is that they’re supposed to. A pack of lunatics who hope to be converted to undeath (led by French underground comics legend Philippe Druillet) run around doing errands for the vampires, but it’s never clear exactly what or exactly why. There’s also a big to-do about a wedding, to be conducted on the stage of the recently shuttered Theatre du Grand Guignol, but I haven’t the faintest clue what significance that’s meant to have. It all ends with a no-budget impersonation of a giant, free-for-all shootout with Tommy guns in the theater’s auditorium, because why the fuck not, really, at this point?

It’s a little misleading for me to rate The Rape of the Vampire at two stars, because it’s actually both much better and much worse than that. On their own, The Rape of the Vampire (strictly construed to mean just the first segment) would merit closer to three and a half, while The Vampire Women would be more like negative one and a half. But since these two radically incompatible shorts have been conjoined Human Centipede style, I’m forced to deal with them as if they were a single organism, at least for the purpose of assigning a final rating.

There’s one sense in which the Human Centipede analogy doesn’t hold, though— in The Rape of the Vampire, it’s the first segment that suffers worst from the graft. It’s difficult to overstate how tight, smart, and effective the first 40-odd minutes of this movie are. Rollin does something with the vampire genre that, so far as I know, had not been attempted since Isle of the Dead over twenty years earlier, and that had never been done successfully before. Vampirism here, at least until the first set of closing credits (each segment has its own), is merely the pattern to which a bunch of seriously messed-up people mold their various manias, phobias, and neuroses. There’s so much well-observed psychology in the opening segment, not just in the treatment of the four mad “vampires,” but for everybody— even the old nobleman, whose true motives remain shrouded in mystery right to the end. Thomas has his crusading need to overcome mental disorder, which concentrates his efforts ever more narrowly on the least treatable of the sisters, until his final failure drives him to madness as well. Mark is so ruled by his fear of insanity that he comes to recognize, instinctively if not consciously, a common mindset with the superstitious villagers whose mob he ultimately joins. Brigitte is pulled this way and that by her loyalty to Mark, her admiration of Thomas, and her compassion for the mad sisters, until she is unable to take any action that might save her when the villagers rise up. And the old man proves to be something like Thomas’s evil counterpart, an astute manipulator of the human mind who is nevertheless incapable of controlling the forces unleashed by his meddling. That focus on mind over monsters is reinforced by the look of the film. For the first time of many over the course of his career, Rollin displays something approximating genius at choosing locations. The condemned chateau— torn down a few months after filming wrapped— is a perfect visual metaphor for the collapsing minds of the people dwelling within it. Meanwhile, the lonesome and forbidding beach where Thomas and the final sister are shot down justly earns its subsequent ubiquity in Rollin’s at-home productions. Between the haunting natural bleakness of the English Channel coast and the exhausted appearance of the salt-rotted jetties, jutting from the sands like the dorsal spines of some millennia-dead dragon, that beach might as well be Tartaros on Earth, all the world’s loss and futile longing concentrated into a few miles of gray sand, gray skies, and gray water. Of course, a lot of credit is due, too, to cinematographer Guy Leblond, who so perfectly captured the visual essences of these morose and morbid venues.

Then along comes The Vampire Women, which undoes everything the film had accomplished thus far, and gets nothing right of its own apart from Jacqueline Sieger’s compellingly strange performance as the Queen of the Vampires. Amazingly, Sieger wasn’t even an actress. A psychiatrist by trade, she was simply one more of Rollin’s friends who appeared in The Rape of the Vampire on a lark. The first blow against the original short’s achievements is struck the moment the continuation decides that there really are such things as vampires. At a stroke, the entire meaning of the film thus far is demolished. Further damage is inflicted when vampirism is revealed to be a bacterial condition, for that pushes the story into sci-fi territory, where Rollin is ill-equipped to follow it. Nor is The Vampire Women helped at all by the time wasted finding excuses to bring dead characters back to life. The truly irredeemable misstep, though, is the abandonment of horror in favor of Eurospy adventure. Rollin has no money for globe-trotting, no money for gadgets, no money for volcano lairs or armies of SPECTRE goons. What he aspires to do in The Vampire Women is time zones beyond his practical reach, and the movie ends up looking like the work of a college theater troupe spoofing Goldfinger on a weekend-long pot bender. Even Leblond turns into a liability, for his somber black-and-white cinematography ceases to look evocative, and begins to look merely cheap. Arguably, then, what we see in The Rape of the Vampire is a teaser for both sides of Jean Rollin’s career. First we get the lyrical, melancholy side that merges the grindhouse with the arthouse; then we get the clumsy, fumbling, too-clever-for-its-own-good side that experiments compulsively, but enjoys about the same success rate as Dr. Bunsen Honeydew.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact