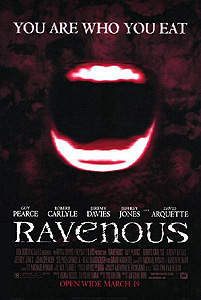

Ravenous (1999) ****½

Ravenous (1999) ****½

Last weekend, the state of Maryland— and judging from the maps I saw on TV, pretty much the whole northeastern quarter of the continental United States— got hit with the biggest motherfucking snowstorm to roll into town since at least 1983. I ended up snowed in at a friend’s house for more than two days with a bunch of folks I’d gone to a party with the night before, and by the end of that time, all nine of us (nine!) were in Cabin Fever Central. Naturally, we averaged a Donner Party joke about once every 75 minutes. Oddly enough, something about being immobilized by nearly 30 inches of snow and joking constantly about eating each other to survive put me in the mood to revisit a little movie that might just have been the best horror flick (if indeed this genre-bender can be so described) of 1999: Antonia Bird’s Ravenous. Chances are you didn’t see this one when it was in the theater (for all of three hours, or so it seemed). You missed out big, let me tell you. For one thing, when was the last time you saw a movie about cannibalism play in mainstream American theaters? (And don't even talk to me about Hannibal— need I remind you that it came out after Ravenous, and had the advantage of being a sequel to one of the biggest hits of the preceding decade?) For another, how long has it been since you’ve seen an American horror flick that successfully struck the delicate balance between having a sense of humor and remaining serious enough to have some impact in the scare scenes? And can you even remember when you last saw such a film that featured a thoughtful script, spot-on direction, and not a single bad performance among the entire cast?

Lieutenant John Boyd (Guy Pearce, from The Road and the unfortunate 2002 remake of The Time Machine) of the US Army has just been promoted to the rank of captain, and awarded a medal in honor of a heroic deed he performed in the recently concluded Mexican-American War. This is rather ironic, for not only is Boyd no hero, he’s an out-and-out coward. You see, Boyd's regiment one day found itself under attack from greatly superior enemy forces; badly outnumbered, the regiment was slaughtered nearly to a man. As soon as he realized the extent to which the tide of battle was turning against his side, Boyd got down on the ground and played dead in an effort to save his own skin, while his comrades died for real all around him. At the battle’s close, Boyd was loaded onto a wagon beneath a whole stack of corpses, his colonel’s blood dripping onto his face and down his throat. But as he explained to his commanding officer, General Slauson (John Spencer, of WarGames), after the fact, “something changed” after a few hours of those hellish conditions. Boyd was suddenly swept by a surge of vigor and bravery; he clawed his way out of the meat wagon and proceeded to seize the Mexicans’ base-camp singlehandedly. (One assumes that the psychological edge conferred upon him by his horrific appearance had something to do with Boyd’s remarkable success.) Needless to say, all of the army’s manuals of standard operating procedure were silent on the subject of officers who commit acts of both conspicuous valor and borderline-treasonable cowardice on the same day, and Boyd’s actions presented his superiors with a real puzzle. Ultimately, Slauson settled upon promoting and decorating Boyd for capturing the Mexican encampment, then transferring him to Fort Spencer, a tiny, out-of-the-way outpost on the western face of the Sierra Nevada mountains, a continent’s breadth away from the general and his brigade.

Fort Spencer, as you’ve probably guessed, is a sort of holding pen for men the army doesn’t quite know what to do with. Its commander, Colonel Hart (Jeffrey Jones, from Howard the Duck and Beetlejuice), is aging, out of shape, and far too intellectually inclined to fit well within the army hierarchy. His top-ranking subordinate, Major Knox (Stephen Spinella), is a drunk. And among the grunts, Private Toffler (Jeremy Davies, who later turned up in the American Solaris remake) is a religious loony, Private Reich (Neal McDonough, from Minority Report and Darkman) is a loose cannon, and Private Cleaves (David Arquette, of Buffy the Vampire Slayer and Scream) is a great lover of any sort of intoxicant. With all the passes through the mountains shut down for the winter, the fort has little reason to exist at all, and its compliment is reduced to the bare minimum necessary to prevent it from falling apart. The only other people there when Boyd arrives are the five aforementioned soldiers and an Indian couple known as George (Joseph Running Fox) and Martha (Sheila Tousey, from Lord of Illusions), who perform most of the handyman and housekeeper functions around the place. Looks like it’s going to be a long winter.

But no sooner has Boyd settled into what he believes will become the routine at Fort Spencer than something happens to disrupt it permanently and completely. One night a man staggers into the fort, half frozen and weak with hunger. After he has sufficiently recovered to handle the strain of a long monologue, the man introduces himself as the Reverend Colghoun (Robert Carlyle, of Eragon and 28 Weeks Later), and explains that he and four other travelers had been attempting the journey to California under the direction of a military man called Colonel Ives. That was more than three months ago. Ives was a lousy guide, and he managed to get the party lost in the mountains just as winter was beginning. When they ran out of provisions, the stranded pioneers killed and ate all of their livestock, and then turned to what little sustenance could be extracted from the frozen woodlands around them. Inevitably, the weakest member of the party died fairly swiftly after that, and with no other options presenting themselves, those who remained turned to cannibalism in order to survive. But having tasted human flesh, Colonel Ives found it to his liking, and the soldier began killing off his companions one by one. Colghoun fled from the cave where the party had been living a few days back, when he realized that there was no one left for Ives to kill except for him and a woman named Mrs. McReady; he’d been wandering alone in the mountains ever since. The official purpose of Fort Spencer and its garrison is to police and patrol the passes through the Sierra Nevadas and protect the wagon trains that traverse them, so Hart immediately recognizes that he and his men must go out in search of the cave of which Colghoun spoke— Mrs. McReady’s life clearly depends on it. He sets out with Boyd, Reich, Toffler, George, and Colghoun the very next morning.

The cave is strangely silent when Hart and his men reach it. Stationing the rest of them outside to guard the approaches, the colonel sends Boyd and Reich inside to look around. What they find puts a rather different spin on Colghoun’s story— Reich turns up a total of five human skeletons in the deepest section of the cave. According to Colghoun, there were only six travelers in his group. Even if Ives had already eaten Mrs. McReady, that would account for only four of those skeletons. You guessed it. Colghoun himself is the cannibal killer, and as soon as he sees that his “rescuers” are onto him, he begins murdering them as well, until only Boyd is left. It’s hard to say whether it’s courage or cowardice that leads him to do so, but as Colghoun closes in on him at the edge of a cliff overlooking a steep valley, the captain turns away and leaps into the abyss. The dense branches of the mountain pines break his fall, and though he lands with a compound fracture of the right tibia, he at least hits the ground alive. And lucky for Boyd, he ends up sharing the hollow beneath the deadfall where he finally comes to a stop with the corpse of Private Reich, whom Colghoun had earlier shot off of the same cliff. He’ll have something to eat, anyway...

A funny thing happens to Boyd while he’s under that deadfall. The more of Private Reich he eats, the stronger and more resolute he feels, and the faster his leg seems to mend. It’s enough to get him thinking about what George the Indian said when he first heard Colghoun’s story. George told Colonel Hart about an old Indian legend— that of the Wendigo. The Indians believed that when a man ate the flesh of another man, a powerful and malign spirit called the Wendigo entered his body, turning him into an insatiable— and virtually indestructible— beast-man. This beast-man would spend the rest of its life killing ever greater numbers of people for their meat, becoming steadily more feral until nothing human was left within its soul at all. What makes Boyd see the connection between the Wendigo legend and his own situation is the idea that the Wendigo-possessed cannibal comes by his unnatural strength and resilience by stealing the life-force from those he eats. Boyd has been a coward all his life, and the only two occasions when he has ever been a Real Man just happened to coincide with his consumption of the flesh or blood of men braver and more vital than himself. All in all, it’s enough to keep his mind occupied when he finally begins the long hike back to Fort Spencer, where his tale of what happened out at the cave is naturally disbelieved by Major Knox and Private Cleaves. It’s also enough to compound his horror a dozen-fold when he meets his new commanding officer— one Colonel Ives. Or, as Boyd knew him before, the Reverend Colghoun. And if you want to know what the fallout from that little reunion is, you’re just going to have to correct the mistake you made back in 1999, and go see Ravenous for yourself.

If it weren’t for two things, Ravenous would be the perfect 90’s horror film. It’s smart, it’s witty, it’s well crafted, and it doesn’t care one whit for the supposedly delicate sensibilities of a modern audience. When director Antonia Bird goes on the attack, she does so with all the fury of the Wendigo itself, but she and screenwriter Ted Griffin are just as happy to engage their audience’s minds in between the shocks. And remarkably enough, Bird has also populated her movie with actors of real talent, who were obviously chosen more for their skill in front of the camera than for their appeal in a poster tacked to the wall of a teenage girl’s bedroom. She has furthermore flown in the face of conventional wisdom about what “a woman’s touch” means by creating the first action-oriented film I’ve seen in ages that was not saddled with even the most perfunctory romantic subplot. The only major missteps she and Griffin make are in the soundtrack and in some of the dialogue. While Bird is to be commended for steering clear of conventional horror movie music, the score she used often has the effect of undermining the mood she seems to be aiming for. Nowhere is this more apparent than in Colghoun’s sudden attack on Colonel Hart and his men, which unfolds to the distracting accompaniment of a festive bluegrass theme better suited to a farce about Mississippi moonshiners. The problem with the dialogue surfaces less often, but is just as disruptive in its way. Though the great bulk of it is very well written (especially considering that this was Griffin’s first credited screenplay), anachronisms like “the over-medicated Private Cleaves” come sneaking out of the characters’ mouths far too often. Period dialogue is a tricky thing. On the one hand, you don’t want to overdo it, or the characters’ words will sound forced and unnatural. But when a movie is set in 1847, it’s important to avoid terms and turns of phrase that didn’t find their way into the English language until the mid-1990’s. Even with these flaws, though, Ravenous deserves much better than the incomprehension and dismissal that greeted it upon its initial release.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact