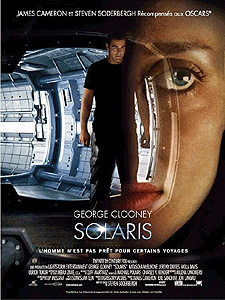

Solaris (2002) ***

Solaris (2002) ***

This year just might restore my lost faith in remakes. Things were looking pretty dire on that front twelve months ago, what with The Time Machine, Planet of the Apes, and Rollerball, but there’s turned out to be light at the end of that tunnel. First there was The Ring, which kicked my ass like a horror movie is supposed to, and now we have Steven Soderberg’s Solaris to consider. This movie seemed to have a lot of people worried before it came out, but I thought there was at least a slim chance for it from the get-go. For my money, Andrei Tarkovsky’s Solaris/Solyaris is exactly the kind of film that merits a remake— a decent movie that should have been better. It’s the kind of sci-fi flick most fans have given up for dead: thoughtful, introspective, intellectually demanding, and not at all concerned with mere spectacle. Unfortunately, the other thing Tarkovsky’s version wasn’t at all concerned with was pacing, and with a running time just a wee bit shy of three hours, the Russian Solaris poses an even greater challenge to the buttocks than it does to the mind. It was just crying out for a director who registers vital signs to take a crack at it— provided, of course, that the vital-sign-registering director in question was not also a fucking idiot. In other words, no Jan De Bont. No John Guillermin. And at this point in his career, no Paul Verhoeven, either. Soderberg I knew next to nothing about, but quick glance at his filmography didn’t turn up any Explosion Movies, and I took that as a promising start. And praise Hell, Soderberg’s Solaris is indeed the first explosion-free sci-fi movie I’ve seen in many a moon. It also goes some way toward correcting many of the flaws in the original.

The story in this version gets moving much faster, but at the expense of a lot of important backstory. Mopey psychologist Chris Kelvin (George Clooney, of From Dusk Till Dawn and Return of the Killer Tomatoes— now there’s a Leave It Off the Resume Movie!) is interrupted in mid-mope one day by a pair of military types knocking at the door to his apartment. The two men play for Kelvin a recording of an interstellar transmission from an old friend of his named Dr. Gibarian (Ulrich Tukur), in which Gibarian asks his bosses to get him in touch with Kelvin. Gibarian is in some kind of trouble, and he believes Chris is the only man who can help him. This, naturally, raises the question of just what kind of trouble the doctor has landed himself in. It’s like this… Gibarian is a scientist working on a space station in a distant star system. His workplace is in orbit around a strange planet called Solaris, which has only recently been discovered, and it is Gibarian’s mission, together with a number of other researchers, to study the place. But not too long ago, all but a handful of the station’s crew have either died or simply disappeared, and the security team that was dispatched by the company underwriting the Solaris mission met the same fate when they arrived to take the situation in hand. Gibarian obviously knows more than he’s telling in his SOS to Kelvin, but one gets the feeling he’s got good reason to be playing it secretive. In any event, Kelvin figures he owes it to his old buddy to do whatever he can, and the psychologist is soon on his way to Solaris aboard the sleeper ship Athena.

Gibarian is dead, and by his own hand at that, by the time Kelvin gets there. Indeed, the only crewmembers left aboard the station are Snow (Jeremy Davies, from Ravenous) and Gordon (Viola Davis), and neither one of them seems to be precisely right. Snow is quite openly a whack-job, talking with tortured syntax and exhibiting wildly non-linear thinking. Whatever’s going on out there hasn’t been kind to him. Gordon is essentially lucid, but she refuses to allow anyone into her sleeping quarters, and is virtually impossible to coax out of them, either. Then there’s the kid. Gibarian’s kid. Gibarian’s kid, who everybody— Kelvin included— knows perfectly well is actually back on Earth, but who is running around the space station unattended nevertheless. The two astronauts, who clearly have some idea what’s going on, refuse to make any explanations to Kelvin until “it happens to [him]” too— only then will he be prepared to listen to them.

“It” happens to Kelvin on his first night in orbit. Kelvin’s dreams are dominated by jumbled memories of his wife, Rheya (Natasha McElhone), a troubled, unhappy woman who killed herself some years ago (which would certainly explain Kelvin’s relentless moping). He dreams of their initial encounter on a commuter train, their subsequent meeting at one of Gibarian’s parties, the hookup at that party which led ultimately to their romantic involvement and eventual marriage, and very vividly of the impossible circumstance of them making love aboard the space station. Then Kelvin is awakened by a slender but strong feminine arm tightening about his chest. Yeah. Rheya’s in bed with him. Not entirely sure whether he’s dreaming, hallucinating, or just losing it, Kelvin starts talking to his unexpected guest, who eventually convinces him that she’s real enough, at least in the sense that she has mass and takes up space, and really is right there in the bedroom with him. Too creeped out to think clearly, Kelvin tricks “Rheya” into climbing into one of the station’s manned space-probe vehicles, and launches her off toward the planet below.

The next day, Kelvin has a talk with Snow. Apparently everyone on the station received a visitor like Kelvin’s at some point during their stay, and the disruption to their senses of reality drove most of them to kill themselves and/or each other. Snow and Gordon never got to that point, but it’s easy to see how much strain the situation has put on their minds. So far as anyone can determine, something down on Solaris— or maybe even the planet itself— is causing the creation of the visitors, though Snow’s opinion and Gordon’s diverge markedly on the question of why. Gordon believes Solaris doesn’t want humans around, and has created the visitors as an attack on the station. Snow is more inclined to think the strange creatures represent some sort of attempt at communication, but he is at a complete loss as to what the planet or its inhabitants are trying to say. Regardless, Snow takes an almost mystical perspective on the subject, and when Kelvin asks him whether “Rheya” might manifest herself again, Snow answers by asking, “Do you want her to?”

Kelvin doesn’t seem to know one way or the other at the moment, but by the time he goes to bed again, his subconscious, at least, has decided that he does. Once again, he awakens to find his dead wife sharing his bed, and being more or less prepared for it this time, he reacts much less violently. In fact, Kelvin comes to believe that whatever lives on Solaris has, in effect, offered him a chance to correct and atone for a mistake that’s been torturing him for years. You see, Kelvin blames himself for Rheya’s suicide, and he has fairly good reasons for doing so. Rheya had gotten pregnant at a time when visible cracks had begun to form in their marriage, and had aborted the pregnancy without saying one word to her husband. Kelvin somehow found out what had happened, and he was furious; although he had never said anything to Rheya on the subject, he did want to have a child with her. Chris thought it was incredibly selfish of Rheya to get an abortion without including him in the decision— or even letting on to him that there was a decision to be made— and coming after months and months erratic behavior and emotional withdrawal on his wife’s part, this latest and largest affront was the final straw. Kelvin packed an overnight bag and told Rheya he was leaving her, and while he changed his mind and came back to their apartment only a couple of hours later, it was too late. She had overdosed on her tranquilizers in the meantime. It is thus understandable that Kelvin would want to look upon the new Rheya that Solaris has supplied him with as being somehow interchangeable with the real thing, and welcome the opportunity to resume a relationship that should, by all rights, be irrecoverably lost. But no matter how closely the visitor Rheya duplicates the dead one back on Earth, she remains a duplicate, and if Kelvin should lose sight of that he will do so at his peril.

In addition to a much shorter running time, the main advantage Soderberg’s Solaris has over Tarkovsky’s is focus. Tarkovsky took on a great many things with his version of this story, and attempted to give more or less equal weight to all of them. Soderberg, on the other hand, takes as his main thrust a Philip K. Dick-like concern with what it means to be human, and how the answer to that question bears on our dealings with each other. Like the Replicants in Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep? (hmmm… Blade Runner…), the visitors are indistinguishable from human beings except for the niggling little detail that they’re entirely artificial creatures. Can they legitimately be considered human? And if not, what does that say about the intrinsic value of sentience, intelligence, reason, emotion— all of those human qualities that we normally like to think are so important? There’s more going on in the movie than this (Tarkovsky’s major theme of the likely inability of humans to come to terms with a truly alien intelligence does rear its head, for example), but most of the other ideas dealt with in the original are reduced to background issues here, and for the most part, I’d say the movie is stronger because of it. The story may lose some of its cosmic-scale ambition in this telling, but the narrowing of the intellectual playing field allows Soderberg to dig deeper into the material than was possible with Tarkovsky’s more scattershot approach. I myself would not have chosen to do that deeper digging in quite the same spot as Soderberg (and therein lies the reason for my incomplete satisfaction with this film), but this Solaris is still a more than respectable effort to reacquaint American cinema audiences with real science fiction.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact