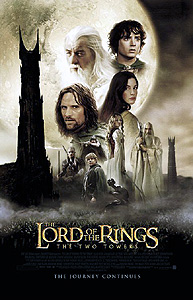

The Lord of the Rings: The Two Towers (2002) ***

The Lord of the Rings: The Two Towers (2002) ***

I’ve been a Tolkien fan ever since I first slogged my way through The Hobbit and The Lord of the Rings back when I was in the third grade. That said, The Hobbit is the only one of his books that I consider an unqualified success, and of the three Rings installments, it is The Two Towers about which I feel most ambivalent. On the one hand, that second volume features some of the best writing and most memorable scenes of the entire immense novel. Not only that, The Two Towers strikes a strong balance in pacing between the glacial deliberateness of The Fellowship of the Ring and the rushed, “Damn it, I’ve got to finish this fucking book sometime before I die” quality of The Return of the King. But despite all that, The Two Towers is really, when you think about it in context, little more than one huge, 450-page subplot. Saruman serves no function in the story that couldn’t just as well have been assigned to Sauron himself, and in terms of the broader plot, the only essential thing the battle against him accomplishes is setting up the alliance between Gondor and Rohan that will later prove so important. Truth be told, the great bulk of The Two Towers could be cut without greatly affecting the integrity of The Lord of the Rings’ narrative. Add to that my great disappointment in how Peter Jackson’s The Lord of the Rings: The Fellowship of the Ring turned out, and I believe you’ll understand why it was with no little trepidation that I walked into the theater to watch this second film in the series. So I’m pleased to report that The Two Towers represents a substantial improvement over its predecessor.

Much has been made of Jackson’s defiance of the studio bankrolling his project by refusing to begin the second film with a recap of the first, and I agree that dispensing with such an intro was a good move. The only gesture The Two Towers makes in that direction is by beginning instead with Frodo Baggins (Elijah Wood) dreaming of the apparent death of the wizard Gandalf (Ian McKellan) at the hands of the Balrog while defending the bridge at Khazad Dum. And even this isn’t much of a rehash, in that we get to see a lot more of the struggle between monster and magician than we did last time. (Incidentally, seeing it again confirmed my first impression that the Balrog would have looked awfully good had it turned up as a level boss in the next House of the Dead game, but that it’s far too obviously computer-generated to be effective on a movie screen.) When he wakes up, we see that Frodo and his companion, Sam Gamgee (Sean Astin), are high up in the mountains, with the fires of Mordor’s Mount Doom just barely visible on the horizon. The two hobbits are quite thoroughly lost, and have just realized that they’ve been going around in circles. They’re also being followed, and therein lies a possible way out of their predicament. Their pursuer, you see, is none other than Gollum (a surprisingly well-done CGI critter with the voice of Andy Serkis), the deranged, cave-dwelling creature from whom Frodo’s uncle stole the One Ring all those years ago. The ring corrupted Gollum almost as thoroughly as its less powerful cousins corrupted the men who became the dark lord Sauron’s Nazgul slaves, and Gollum has been trailing the hobbits with the intention of killing them and recovering “his precious.” Frodo and Sam understandably have other ideas, and essentially end up good cop-bad copping Gollum into leading them to the gates of Mordor. (Sam, in case you couldn’t guess, plays the bad cop in this instance.)

Meanwhile, the exile king Aragorn (Viggo Mortensen), the elf Legolas (Orlando Bloom), and the dwarf Gimli (John Rhys-Davies) are doing a little tracking of their own. Their quarry is the band of Uruk Hai orcs in the service of the increasingly inaptly named Saruman the White (Christopher Lee), who ran off with the hobbits Merry Brandybuck (Dominic Monaghan) and Pippin Took (Billy Boyd) at the end of the last movie. Matters are complicated when a squadron of cavalry from the human kingdom of Rohan get to the orcs first, and massacre the lot of them. The Rohanese horsemen later meet up with Aragorn, and their leader Eomer (Karl Urban, from Ghost Ship and The Truth About Demons) fills him and his companions in on the story. Eomer didn’t remember seeing any hobbits, and he advises Aragon against pressing on to Rohan’s capital; Eomer’s father, King Theoden (The Scorpion King’s Bernard Hill), has come under the influence of an agent of Saruman’s— a loathsome man called Grima Wormtongue (Brad Dourif, of Body Parts and the Child’s Play series)— and can be counted upon to offer what remains of the Fellowship of the Ring no welcome worthy of the name. In fact, Eomer and his men have been banished themselves!

You don’t seriously imagine, do you, that Eomer’s soldiers could have killed Merry and Pippin in their frenzy of orc-slaughter? No. Of course not. The two hobbits got away, alright, as Aragorn’s examination of the orcs’ campsite indicates, but in fleeing the battle, they ended up in the middle of a very dangerous enchanted forest. What makes the place so hazardous is that a certain proportion of the ancient trees within it are really ents, a race of tree-men who don’t take kindly to people trespassing on their territory— especially if those people happen to be carrying axes. Sure enough, Merry and Pippin fall into the clutches of an ent called Treebeard (voiced by Rhys-Davies, but you’d probably never guess that without reading the credits), who makes the distressing pronouncement that he intends to consult with “the White Wizard” on the subject of what is to be done with them. But all is well, for this White Wizard is not Saruman, but rather Gandalf, who was reincarnated in an even more powerful form after slaying the Balrog and being slain by it in turn.

We’ve now got three parallel plot threads established, and they’ll remain distinct from each other for the rest of the film. The main action will concern Aragorn, Legolas, Gimli, and Gandalf in their efforts to save Rohan from conquest at the hands of Saruman’s Uruk Hai army. In this, their principal allies will be King Theoden (at least after Gandalf breaks Saruman’s senility spell and the king sends Wormtongue packing) and his daughter, Eowyn (The 13th Floor’s Miranda Otto), a woman with nearly as much ass-kicking ability as a Pam Grier character. This plotline reaches its climax when Theoden abandons his capital and withdraws to the ancient fortress of Helm’s Deep, where he and his people— with a mere 300 warriors among them— are besieged by some 10,000 Uruk Hai. And while all that’s going on, Merry and Pippin try to convince the ents to take up arms against Saruman themselves. The final, persuasive argument takes the form of a field trip to the edge of the forest nearest to the wizard’s fortress, Isengard, where Treebeard sees with his own eyes the environmental destruction wreaked by Saruman and his forces. Then, untold leagues away from Rohan and Isengard, Frodo, Sam, and Gollum try to sneak into Mordor without drawing the attention of Sauron and his Nazgul (who have traded in their drowned horses for huge, flying dragons) to the mystical burden they carry.

I expect the purists to be horrified by the liberties that Jackson took with the original story here, but if you ask me, it’s precisely those rather drastic changes that account for the superiority of The Lord of the Rings: The Two Towers over The Fellowship of the Ring. What Jackson has done here is give this part of the story something it lacks in the book, and which the last movie lacked as well— an honest-to-God climax. The print version of The Two Towers drags on for another 340 pages after the Battle of Helm’s Deep, which is not depicted as being concurrent with the ents’ attack on Isengard. This isn’t a problem in the book, which was never intended to be read in isolation from The Fellowship of the Ring and The Return of the King, but since no one in their right mind would watch three three-hour movies in succession (and since even those who aren’t in their right minds won’t be able to do so for another year anyway), it would have been an incredibly bad idea to leave the structure of the story as Tolkien had written it when adapting it for the screen. This way, The Two Towers ends with its most exciting events fresh in the audience’s memories, like any good action movie should. This is the movie’s biggest improvement over The Lord of the Rings: The Fellowship of the Ring, which still had a good hour left on the clock when it reached its dramatic high point.

The rest of the film’s superiority comes from Jackson’s more self-assured handling of the material. I still don’t think he’s quite the equal of the task he has set for himself in filming The Lord of the Rings (maybe he should have warmed up by making a movie of The Hobbit first), I wasn’t at all happy to see the not-quite-death cheap shot getting used two more times, and the exposition phase of The Two Towers is so frantically hurried that I can’t imagine anyone who wasn’t already familiar with the novel being able to follow it, but for the most part, Jackson did a much better job this time around. The gawking camerawork I complained about in my review of The Fellowship of the Ring is gone, and the battle scenes are much easier to follow here, despite their much larger scale. The movie version also includes a fair amount of really well handled character development that I don’t remember being in the book at all. The example I’ve heard most people talk about is the tug of war in Aragorn’s heart between the elf princess Arwen and Eowyn of Rohan, which admirably grounds the idea that the age of magic is ending in a context that a person can really relate to, but I was equally impressed with Jackson’s treatment of Gollum. In the novel, it occasions much soul-searching and personal reevaluation when Frodo reminds Gollum that he was once a far more human-like creature called Smeagol before he found the One Ring, but I never got the feeling that Gollum’s cooperation with Frodo and Sam was ever really motivated by much more than a desire to be at least near the ring. Jackson and his fellow screenwriters, on the other hand, give the character a full-on case of split personality, leading to a couple of really great scenes in which the evil “Gollum” and the good “Smeagol” argue fiercely with each other over how to deal with “their” situation.

The final point I want to bring up concerns the CGI effects. There are just as many of them in The Two Towers as there are in The Fellowship of the Ring (indeed, there may actually be a good deal more, what with all the clashing armies and falling cities), but somehow they seem far less obtrusive and annoying. To some extent, that’s just because they’re better done, but a lot of it has to do with the way they’re used. Rather than employing computer animation to present things that exist in defiance of basic physics— like the tower of Isengard, the big-ass staircase in Moria, or thousands of orcs scuttling out of a hole in the ceiling and down walls 400 feet tall— the effects crew here mostly limit themselves to depicting what the studio could never afford to build or hire (with the obvious exception of Gollum, the ents, and the computer trickery used to make the actors playing hobbits and dwarves look like they’re only four feet tall). The result is that there weren’t nearly as many times in The Two Towers when I found myself being slapped out of my involvement in the story by an image that virtually shouted, “Hey you! Yeah, you! Look at me— I am a very expensive special effect! Aren’t you impressed? Well, aren’t you?!?!” Combined with the improvements at Jackson’s end of things, it led me to enjoy The Lord of the Rings: The Two Towers far more than I was expecting to.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact