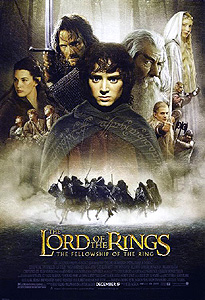

The Lord of the Rings: The Fellowship of the Ring (2001) **

The Lord of the Rings: The Fellowship of the Ring (2001) **

I wanted to like this movie. I really did. Granted, I was skeptical when I first heard that somebody was planning to make a live-action Lord of the Rings movie. Tolkien’s is part of a breed of fantasy that I think is usually best left to animators to realize onscreen, and even then, Tolkien’s work doesn’t exactly have a promising cinematic track record. The Rankin-Bass The Hobbit was excellent— especially considering that it was made for TV— but the same studio’s Return of the King was just barely satisfactory, and the less that is said about Ralph Bakshi’s ill-starred Lord of the Rings the better. But then I learned that Peter Jackson was slated to direct the new movie, and that Christopher Lee had been cast in the part of the traitorous wizard, Saruman. That changed my mind a bit. Jackson is a first-rate director, and I’m such a big fan of Christopher Lee that I’ve even managed to sit through a couple of reels of Safari 3000; with those two onboard, I figured there was hope after all. Then, when The Lord of the Rings: The Fellowship of the Ring finally came out, I held off on seeing it until it arrived at the Senator Theater in Baltimore, the closest approach to one of those grand old movie palaces from the 30’s and 40’s that remains in my area, so as to take advantage of its 70mm projector and super-sized screen. (It’s worth pointing out as an aside that the Senator was actually reckoned a second-tier theater in its day; I can only imagine what the really grand movie houses must have been like!) I found the resulting experience only slightly less disappointing than seeing The Blair Witch Project.

It certainly wasn’t for lack of faithfulness that I didn’t like Jackson’s take on Tolkien. A few incidents were left out here and there, some characterizations were fiddled with, and the motivations of at least one major figure were altered substantially, but The Lord of the Rings: The Fellowship of the Ring is about as close to the book as could reasonably be asked for. The sheer bulk of the film— nearly three solid hours, during which something is almost always happening— makes my usual detailed synopsis seem like an incredibly bad idea, but briefly: A prologue sequence cobbled together out of vignettes from The Hobbit and some of Tolkien’s minor works explains how the Dark Lord Sauron (Sala Baker) created the Rings of Power and gave them to the human, elfish, and dwarfish rulers of Middle Earth in order to give him sway over them and their peoples— Sauron, unbeknownst to the recipients of his gifts, had saved the most potent magical ring for himself, and with it, he could bend the wearers of all the other rings to his will. Sauron lost the war that resulted from his efforts to seize power throughout the land, however, and after his downfall, the One Ring was lost for centuries, until it found its way into the hands of a hobbit named Bilbo Baggins (Ian Holm, from Alien and The Fifth Element).

Flash forward 60 years. Bilbo’s wizard friend, Gandalf (Ian McKellan, of Gods and Monsters and X-Men), has begun to notice signs that Bilbo’s mysterious magic ring may be the lost One Ring, and all of Middle Earth is in a tizzy with rumors that Sauron has returned from the dead and is raising an army in his old stomping ground, the land of Mordor. Some frantic research convinces Gandalf that Bilbo does indeed have the One Ring, and when nine black-garbed horsemen show up in the vicinity of the Shire (where Bilbo and the other hobbits live), the old wizard immediately hatches a plan to smuggle the Ring out of town. Bilbo’s nephew, Frodo (The Good Son’s Elijah Wood), is to take the satanic trinket and flee to the nearest human village, where Gandalf will meet him at an inn called the Prancing Pony. Along the way, Frodo’s friends, Samwise Gamgee (Sean Astin, from The Goonies), Meriadoc “Merry” Brandybuck (Dominic Monaghan), and Peregrin “Pippin” Took (Billy Boyd), join up with him in sneaking past the Black Riders to the village of Bree. They don’t find Gandalf (who is busy just then with an important subplot), but they do meet up with a traveling adventurer called Strider (Viggo Mortensen, from The Prophecy and The Reflecting Skin), who explains that he is a friend of the wizard and helps the Hobbits make a narrow escape when the Black Riders come looking for them at the Prancing Pony. The sinister horsemen harry Strider and the hobbits all the way to the Elven stronghold of Rivendell, to which Gandalf had instructed the ranger to bring Frodo and the Ring. Frodo is gravely wounded along the way, and the entire party is saved from the Black Riders only by the magical intervention of Arwen (Liv Tyler), daughter of the elf king Elrond (Hugo Weaving, of The Matrix).

After Frodo recovers from his injuries, Gandalf drops into Rivendell and explains that the Black Riders are really the Nazgul, or Ringwraiths— the human kings to whom Sauron gave his rings, who were corrupted and enslaved by those rings’ evil power. Gandalf also brings the grim tidings that his boss, Saruman the White (Christopher Lee), mightiest of the wizards, has thrown his lot in with Sauron on the theory that those who cannot be beaten are best joined. Knowing well that his elves will be no match for the combined forces of Sauron and Saruman, Elrond agrees with Gandalf that the One Ring cannot merely be hidden, but must be destroyed. But because the only force that can accomplish that is the hellfire that forged it, and because that hellfire burns in the bowels of Mount Doom, on the outskirts of Sauron’s capital of Barad Dur, that means that some bunch of fools... er... no, heroes— yeah, that’s it— are going to have to sneak the foul thing right into the Dark Lord’s backyard. That bunch of heroes (actually, maybe “fools” would be better...) ends up consisting of Frodo, Samwise, Merry, Pippin, Gandalf, and Strider (who we now learn is really Aragorn, the self-exiled rightful ruler of the fabled land of Gondor), along with an elf named Legolas (Orlando Bloom), a dwarf named Gimli (John Rhys-Davies, from Waxwork and In the Shadow of Kilimanjaro), and a second Gondorian named Boromir (Sean Bean). The rest of the movie follows their travels across Middle Earth, and the eventual disintegration of the party in the face of an especially fierce attack from Saruman’s orc warriors. As the credits roll, two members of the team lie dead (or apparently so— hint, hint), two more are prisoners of Saruman, and Frodo and Samwise have split off from the survivors to sneak into Mordor alone.

Like I said, I really wanted to like The Lord of the Rings: The Fellowship of the Ring. In fact, I was distinctly— almost achingly— conscious of how much I wanted to like it while I sat there in the theater not doing so. So what was stopping me? That’s a complicated question, and will require a complicated answer. The fundamental problem has to do, I think, with the structure of the source material. Contrary to the accepted nomenclature, The Lord of the Rings is not really a trilogy. In a true trilogy, the three parts are each capable of standing on their own as separate works; each has a definite beginning, middle, and end. This is not the case with The Lord of the Rings. Rather, The Lord of the Rings should be thought of as a single book of such stupefying length that the only way to make it work as a physical object was to bind it in three volumes. Thus by making a movie out of The Fellowship of the Ring alone, Jackson has given us a film that ends before the story has a chance to get anywhere, while his determination to squeeze in every little detail that could possibly fit makes for a movie that is episodic to the point of monotony. The result is terribly unsatisfying, for reasons that ought to have been obvious from the very start. To my mind, the thing to do would have been to attempt a single film that would follow the entire story arc from the onset of Frodo’s quest to the final fall of Mordor. The catch, of course, is that it would be necessary to edit the original story with a chainsaw in order to do that— hell, Peter Jackson spent three hours on the first volume alone, and still had to leave out a bunch of stuff! And let’s face it— the Tolkien purists who would constitute the movie’s natural core audience would never, ever stand for such a thing. I mostly understand, therefore, why Jackson made the movie he did— but that doesn’t mean I have to think it works.

There’s something else, too, while we’re on the subject of things not working. I’d like to be able to say that Jackson did the best he could within the limitations imposed upon him by the expectations of a whole planet’s worth of Tolkienites, but I can’t even do that in good conscience. Frankly, our director put in an amazingly slack-assed job on The Lord of the Rings: The Fellowship of the Ring. Pacing has always been one of Jackson’s strong suits, but this movie flows in such a way that the passage of time between and even within scenes just doesn’t make any sense. To cite one glaring example, there is a sequence somewhere in the first half of the film in which Saruman hires a bunch of orcs to rip up all the landscaping around his tower fortress of Isengard, and build a subterranean complex for military training and arms manufacturing in its place. The scale of the orcs’ work is such that the project couldn’t possibly be completed in less than a couple of years, yet the way the sequence is edited makes it feel like the smithies and smelting ovens come online later the same day that the first tree comes down. An equally significant defect is on display in the numerous battle scenes, during which the MTV-influenced editing makes it next to impossible to follow the action.

That’s not all. Jackson also errs in presenting all of his computer-generated settings (themselves a sticking point for someone who has come to hate CGI effects as much as I have) with a kind of gawking awe. It begins right off the bat, when the camera gawks in awe at Mordor. Then it gawks in awe at the Shire (a big mistake there— this is the place we’re supposed to think of as cozy and homey). Then it gawks in awe at Isengard. At Rivendell. At the Mines of Moria. At the elf queen Galadriel’s treehouse city. The only place that doesn’t get gawked at in awe is the lice-ridden village of Bree. This one-note approach even comes to infect Jackson’s handling of such twists and turns as the almost plotless script possesses. There are no fewer than three scenes in which one of the major characters looks to have died, but is then revealed to be okay after all following a decorous period of gearing up for mourning— and two of those scenes concern the same character! As for the two characters whose evident deaths really do remove them permanently from the film, their ends are treated in exactly the same way. After much standing fast in the face of impossible odds, the doomed hero faces his final reverse in slow motion. As he falls, the other characters raise a chorus of the ever-popular “Nooooooooooooooooooooooooooo!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!” before finishing up their little pieces of the battle. Finally, each of the survivors gets his turn at a pensive reaction shot while completely excessive mock-Celtic flute music swells on the soundtrack. This kind of heavy-handed belaboring of the obvious is far beneath Jackson’s talents, and I can’t imagine what made him think it was a good idea.

On the upside, the acting is fair to excellent all around (and only Cate Blanchett as Galadriel stoops to fair), and apart from Viggo Mortensen, who is young enough to be Aragorn’s kid and fails to project the necessary air of world-weariness, the casting is just about perfect. Those few sets and special effects that exist outside of a computer are also extremely impressive— the orc makeup especially. (The orcs are a big deal for me. They were the only creatures among Tolkien’s bestiary for which I never arrived at a satisfactory mental picture— and neither Rankin-Bass’s barrel-chested, no-necked, tusk-toothed midgets nor the pig-wolf men of Dungeons & Dragons and its imitators seemed quite right to me, either— but the first time I saw one of this movie’s orcs, a little voice in my head piped up, saying, “Yes! That’s it!”) There are, in addition, a few cool little design touches scattered throughout the film that go some way toward making up for the absurd impracticality of most of the Middle-Earth architecture we see. I’m thinking in particular of the interior sets for the Baggins hobbit-hole and the costumes for the Black Riders— everything from their arms and armor to the hoof-rot and bad gums on their horses is spot-on. Overall, there are enough good points to give me hope for Jackson’s Return of the King, although I’m not sure I can say the same about The Two Towers (which faces the handicap of having neither an end nor a beginning). We’ll see.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact