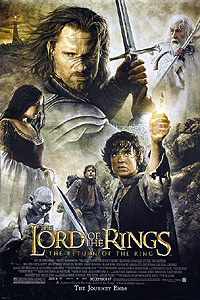

The Lord of the Rings: The Return of the King (2003) ***Ĺ

The Lord of the Rings: The Return of the King (2003) ***Ĺ

Unlike most die-hard movie nuts with a strong strain of geekdom running through their psyches, my reaction to Peter Jacksonís Lord of the Rings movies has been merely lukewarm. This may have something to do with the fact that, much as I like J. R. R. Tolkienís writing, I donít consider him the genius that he is so often made out to be. Not only that, The Lord of the Rings specifically is one of those books that actively resists cinematic adaptationó its length, its scope, and the complexity of its narrative are such that a filmmaker simply canít avoid making lots of hard choices regarding what to cut out and what to rearrange in order to produce the sort of streamlined story arc that a movie requires. The first film in the series met most of my worst expectations, but Jackson and company seemed to have learned a lot of important lessons by the time they set themselves to the task of editing together the second installment, which flows much more smoothly, and which corrects most of its predecessorís most serious defects. And now at last, with the release of the third episode, we get the big payoffó and make no mistake, the payoff is indeed pretty damned big. Iíve still got some complaints here and there, but The Lord of the Rings: The Return of the King is the best of the three by a comfortable margin.

As with the novel, the third volume is the most action-driven of the lot, and most of the story elements are devoted to setting up the two decisive clashes that will determine the fate of Middle Earthó the siege of Minas Tirith by the forces of the Dark Lord Sauron and the smaller, more personal struggle between Frodo and the soul-warping power of the One Ring. Like he did in The Lord of the Rings: The Two Towers, Jackson displays considerable creativity in reminding the audience of what they saw the last time around. A pre-main title flashback sequence tells how a demi-human of unknown race by the name of Smeagol (Andy Serkis) came to possess the lost One Ring, and how it gradually corrupted him into the cave-dwelling creature known as Gollum (still Serkisís voice, but now linked to one of the two or three best CGI creations Iíve ever seen). This is a fine piece of filmmaking on Jacksonís part; Gollumís origin was one of The Two Towersí most important revelations, and Jackson manages to re-establish this key plot point without reusing a single frame of footage weíve already seen. The setting then shifts to the grounds of Isengard, the tower fortress of the rebel wizard Saruman (who wonít be appearing in person this time, to the mild disappointment of Christopher Lee fans like myself), where good wizard Gandalf (Ian McKellen) and Treebeard the ent (another well-done bit of computer animation with the voice John Rhys-Davies) are discussing the importance of keeping Saruman imprisoned within his castle while the main battle against Sauron is joined. Meanwhile, Aragorn (Viggo Mortensen), the exile king of Gondor, engages in some desperate negotiations with King Theoden of Rohan (Bernard Hill), trying to secure that nationís support in the coming war. This is more difficult than it might seem on its face because forces from Gondor were not among the army that rode to Theodenís rescue at the recently concluded battle of Helmís Deep. Leaving Aragorn to his urgent business, Gandalf takes the hobbit Pippin (Billy Boyd) along with him to the city of Minas Tirith, where he also faces a counterintuitively difficult taskó convincing Denethor, the Steward of Gondor (John Noble), that he must resist the coming attack of Sauronís hordes.

And while all that is going on, Frodo (Elijah Wood), Samwise (Sean Astin), and Gollum are closing in on their objective, the volcano Mount Doom, in whose fires the One Ring was forged, and which contains the only force on Earth with the power to destroy it. Though Gollum is outwardly cooperative in this mission, its success is the last thing in the world he wants. In fact, on the pretext of guiding Frodo and Sam through the hazards of Mordor, Gollum is really leading them into a trap. The mountain pass to which he has brought them leads into the cavern where a gigantic spider called Shelob makes her home, and Gollum figures that once Shelob has killed and eaten the hobbits, heíll be able to sneak in while sheís sleeping off dinner, and make off with the ring. Sam knows that Gollum is up to something, but the devious creature does a masterful job of using Frodoís partial corruption by the ring to turn him against his previously inseparable companion, sending Sam away while he and Gollum continue on to Mount Doom. But luckily for Frodo, Sam is a stubborn little bastard, and he turns back to rejoin the quest just in time to save the ring-bearer from being killed by Shelob. Sam doesnít realize his own success, however, because the spider had already stung Frodo by the time he arrived on the scene, and Sam mistakes his friendís paralysis for death. He learns of his error only from a group of patrolling orcs who collect the comatose hobbit and carry him off to the fortified outpost out of which they operate; Sam now gets to go on his second rescue mission in a single day. And after heís pulled Frodoís ass out of the fire once again, the only thing standing between the hobbits and their goal is about 10,000 orcs, trolls, Ringwraiths, and other assorted nasty things.

Returning now to Gandalfís diplomacy, his mission in Minas Tirith isnít going well. Denethor was the father of Boromir, the warrior who was killed by Sarumanís soldiers at the end of The Fellowship of the Ring, and he isnít feeling any too friendly toward either wizards or hobbits these days. He also has a clear enough understanding of his own self-interest to grasp the point that he will be out of a job if ever Aragorn comes home. Finally, recognizing that Gondorís armies are hopelessly outnumbered by Sauronís, Denethor would just as soon leave the fighting to somebody else. Indeed, heíll continue to feel that way even when Mordorís legion arrays itself in the field around his city in preparation for a full-scale siege. But Gandalf is wily enough not to stand on scruple when so much is at stake, and he has Pippin sneak off to light the bonfire beacon that summons the armies of Gondor to war whether Denethor likes it or not. A chain of such beacons reaches all the way to the borders of Rohan, and when Theoden sees that Gondor is calling for his help, he overcomes his reluctance, and musters all the soldiers at his command to ride to his neighborsí aid. Even so, the balance of power is such that Minas Tirith will almost certainly fall, but there remains one more resource to draw upon. Though Elrond (Hugo Weaving) and his elves are packing up to leave Middle Earth for good, the elf king canít go without making one more gesture of support for his human allies. At the instigation of his daughter, Arwen (Liv Tyler), Elrond re-forges the broken-bladed sword that belonged to Aragornís illustrious ancestor, Isildur, who led the victorious fight against Sauron the last time the Dark Lord got it into his head to make trouble. With this legendary blade in hand, Aragorn will have the authority to command an army more powerful than anything thus far mobilized in the War of the Ring. You see, on the road between Rohan and Minas Tirith, there is a haunted mountain beneath which dwell the ghosts of an army that deserted Isildur in his hour of need. These treasonous shades are thus cursed to unlife until such time as their ancient oath to fight for Gondor is fulfilled, and bailing out Minas Tirith now would seem to be as good a way to cancel that debt as any.

A great deal of The Return of the Kingís immense running time (three hours and twenty minutes, for Christís sake!) is devoted to the fighting in and around Minas Tirith. As impressive as the battle of Helmís Deep was in the last movie, The Two Towers has nothing on the third film in this department. This time, Jackson strikes a nearly perfect balance between conveying the whirlwind confusion of large-scale combat and allowing his audience to follow the important points of the action. But equally striking, in its way, is the tone of the various battle scenes. I canít remember the last time I saw so much totally unironic manliness in one movie, so much standing dutifully fast in the face of impossible odds and the like. That really surprised me coming from Peter Jackson, a filmmaker who established himself with movies about horny zombies and kung fu-fighting priests, drug-addicted muppets, and alien conspiracies to use human beings as the centerpiece of the menu at an interplanetary fast food chain. Youíd think a man like that would find it absolutely impossible to keep a straight face in a situation so utterly awash in retrograde masculinity. But the closest Jackson ever comes to subverting the almost Homeric quality of The Return of the King is in the competition between Gimli the dwarf (also John Rhys-Davies) and Legolas the elf (Orlando Bloom) over which of them can kill the most enemy soldiers, which is played mostly for laughs. (ďThat still only counts as one!Ē Gimli bellows in exasperation when Legolas singlehandedly brings down a giant elephant and its twenty or so riders in an act of nearly suicidal daring.) I have to admire a director who is able to rein in his natural impulses when he realizes that they run counter to the needs of his current project, and Jackson has done a better job of that here than virtually any other filmmaker you could care to name.

The other side of the storyó Frodo and Samís perilous trek through Mordoró isnít as attention-grabbing, but it contains some of the best written and most well-played scenes in the movie. Frodo gets yet another not-quite-death scene (bringing his series total toó what? Four? Five?), but this time itís both necessary to the story and handled in such a way that it comes across as more than just another play to manipulate the emotions of the audience. Elijah Wood, Sean Astin, and Andy Serkis between them create one of the most convincing and off-beat... well, one hesitates to say ďlove triangles,Ē but thereís really no other term that captures so well the spirit of the relationship... that Iíve ever seen. And again, Jackson handles it all completely without irony, despite the deluge of homoerotic internet fan fiction this plot thread is sure to spawn. Finally, as a side-note to the Mordor scenes, Iíd just like to say that Shelob is probably the coolest giant spideró CGI or otherwiseó ever filmed.

The only two mistakes Jackson makes in The Return of the King are, unfortunately, relatively major ones. The Ending that Wouldnít is a really bad way for such a strong movie to go out. I realize there are a lot of plot threads to tie up, and I realize as well that the novel has an even more serious case of this condition, but how many ceremonies of coronation and official thanksgiving do we really need? How much hugging and weeping and ďIíll never forget what we went through togetherĒ can anyone stomach before the sheer maudlinness of it all sets off the gag reflex? A more damaging defect, though, concerns the relationships between Aragorn and the two women in his life, Arwen of Rivendell and Eowyn of Rohan (Miranda Otto). Viggo Mortensen and Liv Tyler have nowhere near the chemistry necessary to make it believable that Arwen would want to give up her immortality so as to stay with Aragorn after the elves make their exit, while neither this movie nor its predecessor devotes enough energy to the Aragorn-Eowyn pairing to make it seem like the bond between them consists of anything more than simple infatuation on Eowynís part. To my way of thinking, if you donít have the time to flesh out a subplot of that magnitude, itís better to forego it altogether than to make an offhand gesture in its direction and then leave it sitting there unattended. But those caveats aside, The Lord of the Rings: The Return of the King is a fitting conclusion to what must surely be the most dauntingly ambitious filmmaking project of the last twenty years.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact