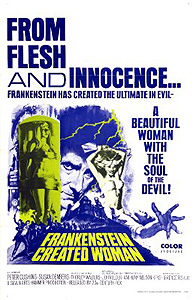

Frankenstein Created Woman/Frankenstein Made Woman (1966/1967) ***½

Frankenstein Created Woman/Frankenstein Made Woman (1966/1967) ***½

Hammer’s third Frankenstein movie, The Evil of Frankenstein, might as well have been the ninth entry in the Universal Frankenstein series instead. To some extent, it’s understandable that the British studio would have taken advantage of a distribution deal with Universal to make essentially the film that had been legally proscribed to them in 1957, but the resulting dissonance between The Evil of Frankenstein and its predecessors was such that understandable or not, it was still a major creative blunder. Luckily, Frankenstein Created Woman marked a return to form. Baron Frankenstein was restored to his original ruthless amorality, Terrence Fisher resumed his rightful place in the director’s chair, and perhaps most importantly, Anthony Hinds (under his traditional “John Elder” pseudonym) provided a screenplay that once again took the series into realms where no Frankenstein movie, from any studio, had ever ventured before.

A belligerent drunk (Duncan Lamont, from The Witches and The Creeping Flesh) is being manhandled toward the guillotine on the outskirts of town by a pair of policemen; one assumes his last request was for a really humongous bottle of wine. The condemned man appears to be having a big old time, heaping taunts, jibes, and belittlement not only upon himself and his captors, but upon the priest engaged to administer his last rites as well. The drunk’s tone changes drastically, however, when he sees a young boy spying on the scene from the bushes a short distance away. The child is named Hans, and he’s the condemned man’s son. Now if there’s one thing the man doesn’t want his kid to see, its his dad’s head dropping into a basket as the decapitation machine does its work, and he attempts to induce the policemen to chase Hans off. It doesn’t work, though. Hans is still on the scene when the blade falls down.

A decade or so later, Hans (now played by Five Million Years to Earth’s Robert Morris) is all grown up and working as some sort of assistant to village physician Dr. Hertz (Thorley Walters, from Dracula, Prince of Darkness and The Psychopath). A respectable occupation has done little to bring the lad respect, however, and none of the townspeople want anything to do with a murderer’s son. Come to think of it, that attitude on the part of his neighbors may well explain why Hans chose to attach himself to the doctor specifically, for Hertz is the subordinate member of a feared and hated partnership, and were there another doctor in the village, the old man would almost surely see the majority of his patients taking their business elsewhere. When we meet Hertz, he is in the middle of a delicate experiment, counting up distractedly to one hour. When the moment arrives, Hertz has Hans open up a pair of heavy, insulated doors at the rear of his basement lab, and pull a long, iron box out of the refrigerated chamber behind them. When Hertz and his assistant open the box, we see that it contains the frozen body of Baron Victor Frankenstein (Peter Cushing, as usual)! Hertz then uses some manner of electrical equipment to revive the baron, at which point he reports on the results of the day’s work. Evidently, it was Frankenstein’s idea in the first place to have Hertz freeze him and revive his body.

We’ll never really learn just how we got here from the end of the last movie, but it would appear that Frankenstein’s escape from his exploding laboratory came at the cost of extensive damage to his hands, and that he therefore now requires the services of a trained surgeon to do the delicate work if he is to carry on his research. Thus he has snuck off to this isolated village (which was presumably outside the reach of his prior three movies’ worth of ill repute) and ingratiated himself to Hertz, who despite his obviously considerable learning in the field of medicine is a foolish, naïve, and not very intelligent man. It would not be unfair to say that Hertz is star-struck with his brilliant houseguest, and he allows himself to be dragged along in whatever direction Frankenstein’s obsessive quest for the secrets of nature might lead. This time around, the objective was to test the baron’s hypothesis that the human soul does not exit the body at the moment of death, but rather hangs around in the corpse for an unknown span of time post-mortem. Hertz and Hans froze him to death and zapped him back to life an hour later, confirming that the soul remains earthbound for at least that long. Meanwhile, Frankenstein has a second project in the works, a sort of forcefield generator, and between the two discoveries, he believes he has found the secret to eternal life. The idea (although there are a few logical holes here that seem to have escaped the filmmakers’ notice) is that a barrier that cannot be penetrated from the outside ought to be impenetrable from the inside as well, meaning that Frankenstein’s forcefield should allow him to trap souls indefinitely. With the soul safely stored, he could then repair whatever bodily damage was the cause of death, re-implant the soul, and jumpstart the body according to his long-established method. Hell, he could even transfer the spirit to a totally new body if the old one were too seriously wrecked to be of use anymore.

As it happens, Frankenstein will get to try out his soul-transference technique sooner than he realizes, and he won’t have to be his own guinea pig this time, either. Hertz offers Frankenstein some celebratory brandy after thawing him out, but the doctor is hardly a wealthy man, and his brandy is extraordinarily bad. The baron sends Hans out to buy a bottle of champagne from the village tavern on his account (it’s amusingly obvious from the tone of this scene that Frankenstein doesn’t actually have an account), and this errand will lead, in a roundabout way, to Hans sharing his father’s fate. Hans, you see, is in love with Christina (Susan Denberg), the innkeeper’s daughter. Unfortunately, Mr. Kleve the innkeeper (Alan MacNaughtan) is just as prejudiced against Hans as everybody else in town, and on top of that, he is neurotically protective toward Christina. This is perhaps forgivable, because Christina has a gimp arm, a deformed leg, and a face covered with hideous scars— as you might imagine, she’s been the butt of just about every cruel joke to be played in the village for the last 20 years or so. Case in point: While Hans is at the inn, negotiating for Frankenstein’s champagne and trying not to get chewed out too badly for wanting to see Christina, a trio of young fuckstick dandies— Anton (Peter Blythe), Karl (The Kiss of the Vampire’s Barry Warren), and Johann (Derek Fowlds, from Tower of Evil and School for Unclaimed Girls) are their names— wander in and begin making monumental pests of themselves. The main idea is to torment Christina, using their wealth, rank, and influence to deter Kleve from doing anything to stop them. Wealth, rank, and influence have no deterrent value for Hans, however, and while Kleve meekly endures his daughter’s humiliation, Hans steps up to pick a fight with all three of her abusers. He’s winning, too, by the time the cops respond to Kleve’s summons and send Hans packing. (One of them curtly dismisses Anton’s wish to press charges against Hans: “Him alone against three healthy young men? That won’t look too good in court.”) Frankenstein and Hertz come looking for Hans shortly thereafter, and get in a few digs of their own at the Fuckstick Dandies’ expense while they’re at it.

Hans, once the police are finished with him, hastens to the Kleve house, where he sneaks upstairs to spend some sweaty, noisy quality time with Christina while her dad closes down the tavern. Meanwhile, Anton and his boys are waiting for Kleve to finish, so that they can break in and help themselves to his wine in misdirected revenge for the succession of embarrassments they endured earlier in the night. Kleve, however, has forgotten his house keys, and he returns to the inn while the Fuckstick Dandies are still on the premises. In order to avoid being busted for theft, the boys jump Kleve and beat the shit out of him with their canes, but in their panic and extreme inebriation, they overdo it and kill the old man. Really not interested in being guillotined, Anton, Karl, and Johann proceed to frame Hans for the crime; it doesn’t take much to turn the cops’ eyes in his direction, and since it just so happens that Christina departs to see yet another doctor about her twisted limbs on the morning of the boy’s arrest, there would be no one able to corroborate his story even if his sense of gentlemanly honor permitted him to tell the authorities that he was busy boning the victim’s daughter while the crime was being committed. Exit Hans.

But only temporarily. Frankenstein sees his assistant’s execution as the perfect opportunity to test his soul-trapping apparatus. Not only that, when Christina returns from the doctor just in time to witness the blade dropping down onto her lover’s neck, she drowns herself in the nearest river out of despair. That means Frankenstein has a nice, fresh body in which to install Hans’s spirit— a little unorthodox, perhaps, but unorthodoxy might as well be the baron’s middle name. And as an added bonus, Frankenstein throws in a full-body reconstruction to go with the resurrection and soul transference; when the Hans/Christina composite wakes up, she/he has the full standard compliment of working appendages, a pleasingly scar-free face, and (inexplicably) a great, big mane of that platinum blonde hair that all the guys who aren’t me apparently go crazy for. At first, the New and Improved Christina has no memories of either previous life, but soon the Hans in her awakens, and she begins a concerted campaign of revenge against the dapper young bastards ultimately responsible for both of her deaths.

The most striking thing about Frankenstein Created Woman is how far afield the mad science is from Baron Frankenstein’s traditional endeavors. Many commentators have seen this as the movie’s central weakness, but I found it to be one of its greatest strengths. From the beginning, the Hammer Frankenstein has been a man who insists upon always moving ahead, pushing the limits of his intellect and abilities. The Curse of Frankenstein had him begin by reviving dead animals, then progress to building an approximation of a man out of recycled corpses. The Revenge of Frankenstein saw him perfect his technique for creating new bodies, and for shuffling brains between them. Only in The Evil of Frankenstein did the baron revisit old experiments, and in that movie, no explanation was ever offered for why he would do so. Consequently, it is much more in keeping with Hammer’s original conception of the character to take his research far beyond the traditional sawing and suturing into the previously unexplored territory of extracting and manipulating the human spirit. There is a revealing exchange of dialogue during Hans’s trial, which makes explicit Frankenstein’s wide-ranging intellectual voraciousness. Called to the stand as a character witness, Frankenstein is asked just what he’s a doctor of, to which he answers, “Of medicine, law, and physics.” When Johann, from his seat in the courtroom, catcalls, “And witchcraft!” Frankenstein turns to him and replies, “To the best of my knowledge, doctorates are not awarded for witchcraft— but in the event that they are, no doubt I shall qualify.” He later claims a mastery of psychology as well (rather anachronistically, as the discipline did not yet exist in any organized form at the time when this movie is set). In that light, the baron’s efforts to put the physics in metaphysics are simply the next logical step for a man who has made all of human knowledge his playground.

That line about doctorates of witchcraft— or rather, the note of dry contempt with which Peter Cushing delivers it— also draws attention to the other way in which Hinds and Fisher have brought the series back on track. Throughout Frankenstein Created Woman, the baron is once again presented as lacking even the most minimal respect or concern for his fellow man, apparently believing that his genius places him above not only law and social custom, but morality as well. In its way, the blithe manner in which he uses his own assistant (to say nothing of his assistant’s girlfriend) as the subject of an experiment which can be of no benefit to either Hans or Christina is a more shocking display of amorality than the series of murders, grave robberies, and elective amputations we saw in the first two films. We now see that Frankenstein is without even a sense of simple personal loyalty! And yet, as in The Curse of Frankenstein and The Revenge of Frankenstein, Cushing’s charisma makes the baron an appealing character to be around for an hour and a half, no matter how openly villainous he may be— and for me at least, that capacity to make an audience root for an utter and unapologetic bastard has always been the big draw of the Hammer Frankenstein series.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact