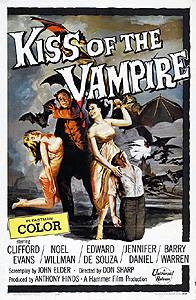

The Kiss of the Vampire/Kiss of Evil (1963) ***

The Kiss of the Vampire/Kiss of Evil (1963) ***

In retrospect— and probably at the time as well— the name of Hammer Film Productions is most closely associated with the studio’s long-running series of Dracula and Frankenstein movies. As great as those films could be, though, none of them would be the one I’d put forward if somebody asked me for one movie to exemplify what Hammer was all about. For that job, I’d pick the relatively obscure The Kiss of the Vampire. To me, you see, the defining quality of Hammer’s output is the constant tension between the dated and the daring, between the stuffy paternalism implicit in most of the movies’ stories and the rebellion against taste and propriety inherent in how that conservative subject matter was presented. Hammer could somehow populate their movies with class acts like Peter Cushing, Christopher Lee, and Andrew Keir, and still make something that would give the censor board the vapors. Meanwhile, they made their fortune by revitalizing a genre that, by the late 1950’s, was widely considered passé if not totally irrelevant, and they did so by using it to push the limits of what a horror movie could get away with. So what better an unofficial manifesto for Hammer than a gothic horror film set at the turn of the 20th century, that begins with the protagonists’ new-fangled motorcar breaking down in the shadow of a vampire’s castle, ends with its hobo-like Van Helsing figure invoking the power of Satan as a weapon against the undead, and all but demolishes the screen of metaphor that had long stood between vampirism and sexual impropriety along the way?

Those broken-down motorists are Gerald (Edward De Souza, from The Phantom of the Opera and The Golden Compass) and Marianne (The Reptile’s Jennifer Daniel) Harcourt, a young couple whom you wouldn’t expect to have the kind of money necessary to buy a car in their day. And in fact they don’t— the car belongs to Marianne’s father, who has lent it to her and Gerald for their honeymoon. As for the nature of the breakdown, it’s a simple matter of an empty petrol tank. (It was easy to run out of gas if you weren’t careful circa 1900, when the only fuel gauge on most automobiles was a dipstick in the tank.) Gerald leaves Marianne with the vehicle to watch their luggage, and marches off to the nearest village in the hope of finding someone who can either sell him some gasoline or tow the car into town. While she waits, Marianne becomes increasingly unnerved, unable to shake the feeling that somebody is watching her. She is being watched, too— up in the tower of the castle overlooking the road from a steep escarpment, a man is spying on her through a telescope. Eventually, Marianne’s paranoia reaches such a pitch that she abandons the car and takes off running in the direction of the village. Before she gets anywhere near it, though, she encounters first a dour old man (Clifford Evans, from The Curse of the Werewolf), who warns her to stay the hell away from the castle and to leave the area altogether if she knows what’s good for her, and next her husband, who was just then returning with a teamster to haul the car away.

Naturally, there is no petrol to be had in so small and isolated a settlement, so the honeymooners take a room for the night at the inn run by an elderly couple called Bruno (Peter Madden, of Fiend Without a Face and Dr. Terror’s House of Horrors) and Anna (Vera Cook, from Shadow of the Cat, who played pretty much the same role as this one in The Brides of Dracula), while hoping to arrange a delivery from out of town. They’re an odd pair, these innkeepers. There’s a furtiveness about them, a fearful, secretive quality that seems to have something to do with that castle on the peak. Bruno’s friendliness toward the new guests seems strangely forced. Anna weeps noisily through the night over a photograph that she won’t let anyone else see, and keeps doing things like setting one place too many at the table come mealtime. Also, there’s only one other person staying at the inn— the same creepy old guy who warned Marianne away from the castle earlier. He keeps to himself, rarely emerging from his room except to drink up as much of Bruno’s brandy as he can before passing out, and all either innkeeper seems to know about him is that he’s a doctor or a teacher or something. He also very obviously knows about those vampires who must be around here somewhere (The Kiss of the Vampire, and all that), but that everyone in town invariably goes out of their way to avoid mentioning. The morning before Gerald and Marianne’s arrival, the other lodger’s daughter was buried in the village churchyard. Professor Zimmer— for that is the sour-faced recluse’s name— showed up late (and drunk) to the funeral, interrupting the ceremony between the end of the vicar’s benediction and the beginning of the burial proper to drive a sharp-headed spade through the lid of the coffin and into the dead girl’s heart. Zimmer’s performance wasn’t nearly as horrid as the corpse’s, though. As the spade pierced her heart, the deceased let out a terrible shriek, and vast gouts of conspicuously uncoagulated blood sprayed out through the rent in the coffin lid. Nevertheless, when asked directly by Gerald to let him in on the village’s big secret (which he isn’t so big a fool as not to notice, even if he has no clue as to its nature), Zimmer will say only that no one in town is going to answer his questions, and that if Gerald is a wise man, he’ll take his wife and leave without asking any more of them.

It’s already too late for that, however. Gerald and Marianne have scarcely settled in when a coachman arrives at the inn with a message from Dr. Ravna, the local squire (Noel Willman, from The Vengence of She, who would also turn up in The Reptile a few years later), inviting the stranded travelers to have dinner with him and his family at the castle. Yes, that castle. And since nobody will tell the Harcourts why accepting the invitation is such a terrible idea, they think nothing of shaking their heads at the prejudices of the local rustics and climbing into the coach. Ravna, in contrast to most old-fashioned vampires, is a family man. He has a son named Karl (Frankenstein Created Woman’s Barry Warren) and a daughter named Sabina (Jacquie Wallis), both of whom are, if anything, even more hypnotically charming than the doctor himself. Karl plays a mean piano, too; Marianne lapses almost literally into a trance when she hears him tickle the ivories. But there’s also a fourth member of the Ravna household to whom no one introduces the guests. In fact, this other girl (Twins of Evil’s Isobel Black)— whom we will come to know later as Tania— takes pains to stay completely out of sight while the Harcourts are at the castle. Instead, she skulks off to the cemetery to pay a visit to the grave of Professor Zimmer’s daughter. You guessed it. She’s waiting for the dead girl to dig her way out, so that she can escort her to her new home, and she’s pretty distraught when she impatiently begins digging herself, and comes upon the handle of the spade the professor drove through his daughter’s heart. Zimmer has been waiting for this moment, too, hiding in ambush behind a nearby mausoleum. Evidently these vampires don’t have the superhuman strength we’ve become accustomed to seeing in recent years, because Zimmer swiftly overpowers Tania, and is prevented from dispatching her only when she manages to get a good bite in. Zimmer lets the vampire girl go, and races home to sterilize his wound with both holy water and fire.

Any guesses as to who Tania was before she became Sabina Ravna’s playmate? Why yes— she’s the intended occupant of that extra place Anna keeps setting at the kitchen table. Tania was the innkeepers’ daughter, but Dr. Ravna took a liking to her a few months back, and that was the end of her mortal existence. Most of the local families have lost a son or daughter to the vampires, as a matter of fact, for they’re not just a clan of bloodsuckers, but a Satanic cult as well, and cults can’t long survive without converts, even if their adherents are immortal. Consequently, I imagine you’ll see what’s happening when Ravna’s kids stop by the inn— on a densely overcast morning, in a carriage with heavily curtained windows— to invite the Harcourts to a masquerade at the castle this coming Saturday. While Sabina neutralizes Gerald with drugged champagne, Karl dances Marianne into exhaustion, and then leads her into his father’s clutches after changing into a mask identical to the one with which the Ravnas provided Gerald. When Gerald comes to hours later, the party has broken up, there’s no sign of Marianne, and everyone remaining at the castle puzzlingly insists that he attended the ball alone. What’s more, none of Marianne’s possessions remain at the inn when Gerald returns, and Bruno joins the Ravnas in claiming ignorance of any Mrs. Harcourt. A talk with a policeman (John Harvey, from X: The Unknown and The Stranglers of Bombay) avails Gerald nothing, but now that Harcourt is so obviously in over his head, Professor Zimmer at last breaks his silence on the truth about the Ravna family. It isn’t too late yet to save Marianne, but time is running out fast. Gerald will have to return to the castle that evening and get his wife out the door by whatever means may be necessary. Zimmer, meanwhile, will employ the occult knowledge he’s gained over his long years of study, casting a spell on the castle that amounts (I think— it’s the only thing that even sort of makes sense) to inducing the Devil to call his minions home to Hell.

That spell, and the ending attendant upon it, are easily the worst things about The Kiss of the Vampire. The magic Zimmer uses against the vampires is explicitly black— he says he’s going to use the power of evil against itself— and screenwriter Anthony Hinds (writing under his usual “John Elder” pseudonym) never really explains how that’s supposed to work. In practice, it means Ravna’s castle being overwhelmed by a flock of rubber bats even worse than the ones in Billy the Kid vs. Dracula, which proceed to go all Bodega Bay on the doctor, his kids, and the vampire cultists. It’s frankly pretty embarrassing, especially considering how good The Kiss of the Vampire had been up until then. In the Zimmer girl’s funeral, it has one of the very best opening scenes Hammer ever devised, it employs the studio’s flexible approach to vampire lore to very good effect (I especially love the moment when Zimmer drives the Ravna kids away from the inn by pointedly observing that the rain has ended and the clouds seem to be breaking up), and it has some of the finest cinematography and production design ever offered up by a company that was justly noted for its high standards in both of those departments. The detour through Kafka territory after the Ravnas’ masquerade is both puzzling on plot-logic grounds and underdeveloped in relation to the rest of the story, but it remains a pleasantly unexpected touch nonetheless. My favorite aspect of the film, though, is how concisely it encapsulates the contradiction between Hammer’s status as the foremost envelope-pushers in the British movie industry and the intense social conservatism that shines through practically all of their output in the horror genre. Just watch the scene that plays out between Ravna and Gerald when the latter comes to spring Marianne from the vampires’ clutches. In no other movie that I can think of from this era is it so glaringly obvious that the real threat posed by the vampires lies in their capacity as sexual emancipators of women, and it’s hard to think of anything more obnoxiously retrograde than horror at the prospect of women having a say in the expression of their own sexual identities. Nor is there any suggestion whatsoever that we aren’t supposed to side unquestioningly with Gerald and Zimmer as they struggle valiantly to stuff Marianne back into her chastity belt. And yet the very act of making a horror movie so blatantly about sex (it’s even called The Kiss of the Vampire, for heaven’s sake!) was almost unutterably transgressive in Great Britain in 1963. The true uniqueness of Hammer was that it was a studio of radical old fogies and prudish libertines, and nowhere does that come across more strongly than in The Kiss of the Vampire.

This review is part of a much-belated B-Masters Cabal tribute to all the living dead things that we’ve been negelecting in favor of zombies all these years. Click the link below to read all that the Cabal finally came up with to say on the subject.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact