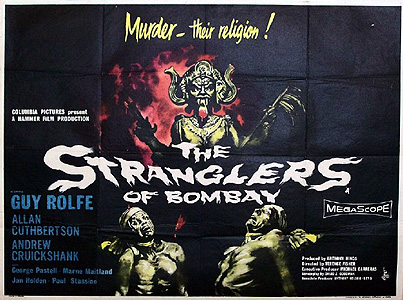

The Stranglers of Bombay (1959/1960) ***

The Stranglers of Bombay (1959/1960) ***

Actors aren’t the only ones who can get typecast. In fact, sometimes it happens to entire studios. Despite their big image makeover in the mid-1950’s, Hammer Film Productions didn’t dedicate their efforts exclusively to horror afterwards. Even disregarding the super-low-budget travelogues and musicals that the studio continued to crank out in two- and three-reel formats until the market for supporting shorts dried up at the end of the decade, Hammer’s offerings during the second half of the 50’s were a little more diverse than the traditional critical focus on Count Dracula, Baron Frankenstein, and Professor Quatermass would imply. There were noir pictures like Blonde Bait and The Snorkel, military comedies like I Only Arsked and Don’t Panic, Chaps!, gritty World War II dramas like The Camp on Blood Island and The Steel Bayonet. There was even a parodic take on The Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde called The Ugly Duckling, which sounds almost like a trial run for The Nutty Professor. And of the most direct relevance to the subject of typecasting, there was The Stranglers of Bombay, a movie that blurs the lines between historical melodrama, Third World adventure, and gothic horror in a way that recalls Tower of London on one hand and East of Borneo on the other. This was the film for which Hammer introduced the “sell it with sadism” approach to historical subjects that would reach its apotheosis in Rasputin, the Mad Monk seven years later, making it easy for both exhibitors and overseas distributors to market it as the horror picture fans (especially foreign fans) would naturally expect, without leaving the latter feeling as though they’d been completely hornswoggled.

The exotic setting is India in 1829, and the ghoulish subject matter is the opening stages of the struggle between the British East India Company’s private army and the Thugs. Note that capital T. These aren’t thugs in the modern, colloquial sense we’re talking about, but rather the originators of the term. As is often the case with historical topics associated with the era of European colonialism, consensus on exactly who and what the Thugs were has largely evaporated in recent decades, but the central fact is that they murdered, generally by strangulation, an awful lot of travelers in the Indian countryside during the first half of the 19th century, to the extent that the East India Company’s leadership (which generally didn’t give two shits what happened to the natives so long as the firm’s monopoly on trade between India and the rest of the British Empire remained profitable) was eventually moved to crack down on their activities. Otherwise, the Thugs have been variously characterized as everything from ordinary bandits with an extraordinary flair for showmanship, to a sort of proto-mafia, to a secret caste of hereditary criminals who used ritual murder as a sacrament in honor of the destroyer-goddess Kali. I’m inclined to favor some combination of the above— perhaps a proto-mafia whose flair for showmanship led them to pose as a centuries-old murder cult— but that’s rather beside the point just now. What’s important for our present purposes is that in 1959, British popular culture still uncritically accepted the notion of a “Thuggee Cult.” (A semantic note: “Thug” is an Anglicized rendering of the Hindi word for “thief,” which ultimately derives from the Sanskrit for “to deceive,” and “Thug” is to “Thuggee” as “robber” is to “robbery.”) The Stranglers of Bombay, for its part, goes its culture as a whole one better, favoring the most lurid interpretation of the Thugs’ beliefs, behavior, and position in Indian society that could have been granted any credence in its day. And really, would we expect or indeed desire any less from what might just be the world’s first pure Thugsploitation movie?

The Stranglers of Bombay announces its intentions in no uncertain terms by beginning with the high priest of the Thuggee Cult (George Pastell, from Maniac and The Curse of the Mummy’s Tomb) delivering a sermon on the religious import of garroting as many motherfuckers as opportunity and sound serial-killing practice will allow. Apparently it has something to do with this one time when Kali fought a monster whose every drop of spilled blood gave rise to a complete new body. (Great. Now I want really want to see Kali vs. Reptilicus, even though I know perfectly well that it would end up being made by UFO International…) Meanwhile, Colonel Henderson (Andrew Cruikshank) is being raked over the coals by his East India Company bosses for his inability to protect the caravan routes under his jurisdiction against brigandage. Or at any rate, the company men are assuming that brigandage is the problem. The truth is, they don’t really know what’s been happening to their caravans lately, because they’ve been disappearing without a trace down to the last man, mule, and bundle of merchandise. A few hundred dead coolies every so often are no big deal, of course, but mules cost money, to say nothing all the tea and silk and mangos that aren’t making it to market! The company reps have already tried complaining to Patel Shari (Marne Maitland, of The Reptile and Shaft in Africa), but he was quick to remind them that he hasn’t really been patel (that is, local headman) since the Brits showed up; he has only such power and authority as it pleases the company to let him pretend. Henderson is thus rather on the spot, but he’s also lucky enough to have a subordinate as clever as Captain Harry Lewis (Guy Rolfe, from Mr. Sardonicus and Dolls) on his staff. Lewis proposes releasing an officer from his regular duties, so that all of his time and attention may be devoted to solving the mystery of the vanishing caravans. Naturally, he has himself in mind for the job when he offers this suggestion, and in fact he’d probably be pretty good at it. If nothing else, Lewis is the only officer serving under Henderson with any initiative, cultural sensitivity, or insight into how the natives actually live. Plus he’s about due for a chance to earn another promotion, and it was, after all, his idea in the first place.

So obviously Henderson passes Lewis over, and assigns the task to Captain Christopher Connaught-Smith (Allan Cuthbertson, of Thin Air and Captain Nemo and the Underwater City) instead. Connaught-Smith had never set foot in India before responding to the colonel’s summons. He knows nothing about the land or its people, and would furthermore consider knowing such things to be coarse and ungentlemanly. He’s a lazy, arrogant, willfully incompetent sod, and even if he could find his ass with both hands and an astrolabe, he would never stoop so low as to do it himself— that’s what one pays butlers for, don’t you know. But you see, he went to the same school as Colonel Henderson, and that’s plainly what really matters in situations like this one. To the surprise of absolutely nobody, Connaught-Smith’s idea of “investigation” is to sit around his headquarters in Bombay, hauling in natives selected seemingly at random, and roughing them up until he’s satisfied that they know more than he does about the lost caravans. The chances of this approach yielding any remotely useful information are even worse than they appear, too, because the officer to whom the captain delegates the roughing-up duties— the half-Indian Lieutenant Silver (Die Screaming, Marianne’s Paul Stassino)— is himself an undercover Thug. And as if all that weren’t bad enough, Connaught-Smith won’t even let Lewis do the job right in a subordinate capacity— in fact, even when huge and obvious clues like a mass grave hidden in the jungle fortuitously fall into Lewis’s lap, neither Connaught-Smith nor Henderson will entertain for one second the possibility that the other officer might be on to something. Lewis eventually resigns his commission in disgust, and takes it upon himself to crack the case as a private citizen.

That plan isn’t half as hopeless as it sounds, either, for Lewis actually has a personal connection to the Thuggee Cult. His native servant, Ramdas (Tutte Lemkow), has a brother by the name of Gopal (David Spencer, from Battle Beneath the Earth and The Earth Dies Screaming), who has recently disappeared. This is not because Gopal fell victim to the Thugs, but rather because he has dropped out of society to join the cult. Ramdas goes missing as well when Lewis gives him leave to search for his vanished brother, and this double disappearance convinces Lewis that his valet was on the right track. He sets off at once to follow in Ramdas’s footsteps, but the Thugs have eyes and ears in all strata of Indian society, and they’ve noticed by this point that Lewis an enemy worth worrying about. It soon becomes a valid question which is the hunter and which is the prey.

The Stranglers of Bombay has acquired a curious form of notoriety over the last fifteen years or so. If you’ve read anything on the subject of British horror movies published since the mid-1990’s, you probably know this film as the one starring Marie Devereaux’s tits. If that’s what brings you to The Stranglers of Bombay, though, I’m afraid you’re going to be disappointed. Despite what all those oft-reproduced production stills might imply, Devereaux’s role was a non-speaking bit-part, entailing nothing more than to hang around the temple of Kali and occasionally to react with rapturous arousal to the fates of the cult’s victims. The censors of 1959 would have found the latter business objectionable even without the exposed acres of sweaty cleavage, and so far as I’ve been able to determine, only the prints exported to France retained any of Devereaux’s closeups. Certainly they’re missing from all three of the currently available DVD editions— even the Italian-language Region-2 release. Unless you’re specifically looking for her in the crowd at the temple, you could easily miss her altogether.

So instead, what should draw you to The Stranglers of Bombay is the chance to see an interesting and little-addressed historical subject treated in several most unusual ways. As history, The Stranglers of Bombay undoubtedly is not particularly good, and is probably very bad. However, unlike most dodgy historical films, it both proceeds with clear logical consistency from what was popularly assumed to be true at the time it was made, and has firm grounding in a legitimate source for the period and events that it dramatizes. The intention originally had been to adapt John Masters’s 1952 novel, The Deceivers, but Hammer had been unable to secure the film rights. Consequently, screenwriter David Zelag Goodman (later of Straw Dogs and Logan’s Run fame) turned to the memoirs of Major General Sir William Sleeman, the East India Company officer who presided over the extirpation of Thuggee. While the understanding of Indian culture that the movie reflects looks suspect at best today, its basis in the experiences of a firsthand observer of 1830’s India at least prevents it from appearing a totally fanciful confection of ignorant stereotypes. If nothing else, this version of Thuggee seems a lot more credible (and a lot less insulting) than that in Indiana Jones and the Temple of Doom. Furthermore, perhaps as a side effect of being made while the dismantling of the British Empire was ramping up to its early-60’s peak, The Stranglers of Bombay hints at an unexpectedly ambivalent attitude toward colonialism itself. Goodman never goes so far as to suggest that there was anything inherently wrong, immoral, or even misguided about colonialism per se, but he’s not at all shy about depicting colonial administration as a haven for cronyism, corruption, and pigheaded ineptitude. If he can be said to display here anything as coherent as a perspective on Britain’s former position as Mistress of Southern Asia, it would seem to be something along the lines of, “You know, if we’d had a few more Harry Lewises on the job, and not quite so many Christopher Connaught-Smiths, there might never have been a mutiny or an Indian National Congress or a Quit India movement.”

Moving beyond the film’s surprising reluctance to be historically indefensible and culturally appalling, it has the further virtue of being technically not at all the sort of picture you would expect from this premise in this era. To begin with, it was shot in black and white, foregoing the gaudy Eastmancolor and Pathecolor that had already become one of Hammer’s most recognizable calling cards. Color cinematography had been part of the standard package for non-bottom-feeding exotic adventure movies since at least the 1940 version of The Thief of Bagdad, and had figured in every one of the films that Terence Fisher had directed for Hammer previously. The crisp, harsh monochrome subconsciously puts The Stranglers of Bombay on the same tense emotional footing as Hammer’s formative noir thrillers or the horrific sci-fi hybrids directed by Val Guest. Guest’s approach as a writer, meanwhile, is recalled by the pessimism of the story, in which Lewis’s eventual success in forcing his superiors to recognize the existence of the Thuggee Cult is at best a moral victory; certainly it does no immediate good to any of the hundreds of people whom he is unable to save over the course of the film (in fact, Lewis manages to save literally nobody), and one of the cult’s major enablers remains not merely unpunished as the credits roll, but indeed unexposed. As befits its origins at a studio most strongly associated with horror, The Stranglers of Bombay is an atypically dark and morbid adventure movie, and remains well worth seeking out despite a few clunky performances and an ending that proves unsatisfying in bad ways as well as good.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact