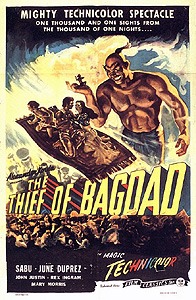

The Thief of Bagdad (1940) **

The Thief of Bagdad (1940) **

It might seem strange at first that a prestigious, successful film like The Thief of Bagdad would not have received the talkie remake treatment to which so many other silent hits were subjected in the early 1930ís. But such an undertaking would have been frightfully expensive, and the fortunes of the United Artists studio, which produced The Thief of Bagdad, had declined precipitously during the second half of the 20ís. Indeed, by the beginning of the sound era, UA had gotten out of the production business completely, becoming instead a distribution clearinghouse for independent movies. A deal with United Artists could guarantee Hollywood-scale circulation, but a filmmaker seeking to take advantage of the UA network would have to come up with the initial funding himself. With the Great Depression in full swing, only the major studios could have afforded an outlay worthy of Douglas Fairbanksís groundbreaking fantasy epic, and so the decade passed without the remake one might naturally have expected. Then came British producer Alexander Korda. The cost of movie-making was considerably less in the Isles than it was in Hollywood, and the money was there to do a new Thief of Bagdad justice. Furthermore, a gaudy, escapist fantasy must have seemed like exactly the prescription to draw in an audience seeking relief from the oppressive, grinding suspense of the Sitzkrieg. The limited returns available from the relatively small British box office might normally have deterred Korda anyway, but distribution through United Artists meant access to American audiences, too. Thatís where the real money was by 1940, and the remade Thief of Bagdad would remain a winning proposition even after the launch of Hitlerís bombing offensive against Britain drove production across the ocean to the United States.

One of the problems with the old Thief of Bagdad was that there was way too much going on for it to have much chance of coming together into a coherent whole. Evidently the writers of the remake hoped that if they made it twice as busy as the original, people would give up trying to make sense of it and just assume that anything so complicated must fit together somehow. If you think Iím exaggerating, consider that this is a movie that spends most of its first 40 minutes on a flashback! In Basra, amid much annoying singing on the part of its crew (thereís quite a bit of annoying singing in this movie, as a matter of fact), a huge and impressive sailing ship pulls up to the seaside docks. For some reason, the commander of the vessel (Conrad Veidt, from The Man Who Laughs and The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari) is very interested in a blind beggar named Ahmad (John Justin), and he sends his slave, Halima (Mary Morris), to find and collect the sightless bum. Whatever is going on, it obviously has to do with the catatonic girl (June Duprez, of And Then There Were None and The Brighton Strangler) lying with a strange, fevered restlessness in the harem of the ship-captainís palace. Eventually, Halima finds the beggar, and brings him and his uncannily intelligent seeing-eye dog to her masterís house. Once he has been fed and rested, Ahmad begins telling his curious story to Halima and the other women of the harem, triggering the flashback that will consume the next three reels or thereabouts.

Ahmad was not always blind, nor was he always a bum. And whatís more, his faithful, furry companion was not always a dog! In fact, Ahmad was once the king of Baghdad, hated and feared as a bloodthirsty tyrant by all of his subjects. He was unaware of his grim reputation, however, nor did he truly deserve it, for the day to day business of running the kingdom was conducted by Jafar, the grand vizier. Jafar was a cruel and evil man who did everything in his power to keep the king in ignorance and dependency, and it will probably surprise few of you to learn that he and the scheming sea captain are one and the same. Ahmad chafed against the conventions of Oriental kingship, and longed for a closer connection with his people; with that in mind, Jafar suggested one day that he take some time off to go about his capital in secret, disguised as a commoner. It was all a trap, however, for no sooner was the king outside the walls of his palace than Jafar had him arrested and locked in the dungeon. Ahmadís protests that he was the cityís ruler were presented by the grand vizier as proof that he was mad, and he was scheduled for beheading the following morning. The irony was that it was precisely Ahmadís habitual seclusion that enabled the usurpation to succeed, for few people in Baghdad had ever seen the king with their own eyes, and it was an easy matter for Jafar to circulate the story that Ahmad had died suddenly in the night. As for the dog, he was a boy named Abu (Sabu, from Cobra Woman and Jungle Hell), who led a carefree life in the streets of Baghdad as a petty thief. His thieving eventually brought him to the same cell where Jafar had imprisoned Ahmad, and it was Abuís quick and sticky fingers that allowed the deposed king to escape the executionerís scimitar. Abu stole the head guardís keys right out of his pocket as he was brought in, and Jafarís men found nothing but an empty cell when they came to carry out the death sentences upon Ahmad and Abu.

Ahmad and Abu fled to Basra with an eye to becoming sailors, and the king revealed his true identity to his companion along the way. But if escape from Jafar was the goal, then Basra was exactly the wrong destination, for the usurper was coming to visit the cityís aged sultan (Miles Malleson, from The Hound of the Baskervilles and The Brides of Dracula) in the interest of winning his daughterís hand in marriage. Thatís rightó itís the Princess of Basra muttering incoherently to herself at the edge of consciousness in that bed back in the present day. The sultan had an absolute mania for mechanical toys, and Jafar hoped to seal the deal for his wedding by offering the old man an enchanted, flying clockwork horse. Unbeknownst to either potentate, however, Ahmad had already snuck into the palace with Abuís help in order to steal a close-up look at the princess (his curiosity was whetted by reports that the sultan had pronounced a death sentence upon anyone who so much as looked at his daughter), with the predictable result that the two of them fell hopelessly in love. When the princess learned what was in store for her, she fled the city, instructing her slaves to pass word on to Ahmad that he should look for her in Samarkand. (That, by the way, would be roughly equivalent to me skipping out on an appointment at Baltimoreís inner harbor, and telling the other party to meet me in Vancouver instead.) The sultanís soldiers found Ahmad and Abu while searching the palace grounds for the vanished princess, and Jafar used his sorcery to blind Ahmad and turn Abu into a small, shaggy mutt, cursing them both to remain in their transformed states until such time as he held the princess in his arms. Jafarís agents later found the princess in a slave market somewhere in Turkestan, but when they returned her to their lord, she lapsed into her current trance-like state. Jafar now hopes that by reuniting her with Ahmad, he can restore her to consciousness, and move ahead with the long-delayed wedding. Itís going to take some pretty smooth subterfuge to arrange everything without revealing his involvement, however.

The princess does indeed come around when Halima brings Ahmad to her, but she is distraught to discover that her lover has gone blind. Halima then mentions that a ďfamous doctorĒ is in town, and that this doctor has the power to restore Ahmadís sight if the princess will go to him. Naturally, Halima leads the princess to Jafarís ship, where she is immediately locked up below decks for the sea voyage to Baghdadó a voyage which demonstrates that Jafarís wizardry is even more powerful than we had believed, since Baghdad is some 400 miles inland from Basra, and the only way to get there by sea would be to bring the sea with you! Along the way, Jafar tries every trick in the book to win his captive over, even stooping to blackmail by explaining that the only way to cure Ahmadís blindness is for the princess to allow Jafar to hold her. The princess miserably consents to his embrace when she hears that. Taking advantage of said consent is not a very smart move on Jafarís part, though, for the first thing Ahmad and Abu do upon the termination of the wizardís curse is to steal a boat and launch off in pursuit. Jafar raises a tempest to thwart their chase, but I think we all know that the magicianís respite is going to be temporary at best.

In point of fact, Jafar has unwittingly set his enemies on the path toward acquiring the very means that will enable them to defeat him. The little boat which our heroes snagged from the Basra docks is no match for the wizardís storm, and Ahmad and Abu are separated when the fragile hull disintegrates. Abu washes up on an island, putting him in just the right place at just the right time when the current carries a bottle containing an imprisoned genie ashore. Abu releases the genie (Rex Ingraham, who would play a rather similar role in 1001 Nights), and although it is initially vengeful and belligerent, the little thief soon tricks it into serving him, granting him three wishes. Abu wastes the first wish on a pan of sausages (evidently the Thief of Baghdad does not keep Halal), but heís a bit more careful thereafter. His second wishó to discover where the storm deposited Ahmadó is beyond even the genieís power, but the magical creature is able to arrange for Abu to have a chance at finding out for himself. The genie flies his temporary master to the Roof of the World, where Abu might steal the All-Seeing Eye from a giant statue of a Hindu goddess. Itís a tall order (a giant spider and an octopus pit are involved), but Abu is successful, and a contemplative gaze into the Eye reveals Ahmadís location. I donít know about you, but Iím not even going to try to figure out how the fugitive king managed to wash ashore in fucking Utah. Wish number two brings Abu to Ahmadís side by Genie Express, and another look into the All-Seeing Eye shows Ahmad that Jafar has absconded to Baghdad with the princess after murdering the sultan, eliminating the final impediment between him and his matrimonial ambitions. A bit of careless talk results in Ahmad being wished back to Baghdad alone and unarmed; he falls rapidly into Jafarís clutches, while Abu remains in the Utah badlands with no genie, no way home, and no apparent means of rescuing his friend. He does still have that All-Seeing Eye, thoughÖ

The Thief of Bagdad won Oscars for both production design and special effects, meaning essentially that it was recognized at the highest official level for looking really fucking cool. Unfortunately, looking really fucking cool is just about all this movie is good for. The sets, props, and costumes are beautiful, the matte effects set a whole new standard for movies shot in color, and indeed the only material aspect of the production that is anything less than stunning in the context of 1940 is the puppet used to represent the giant spider. The latter creature frankly isnít a whole lot better than the monster sand flea in the 1924 version, and the battle between it and Abu is likely to make most experienced viewers wish for Willis OíBrien. In every other respect, however, The Thief of Bagdad is seriously wanting. The storyline is episodic to the point of distraction, serving more as a series of setups for dazzling special effects than as a structured, intelligible narrative, and the movie, though slightly shorter than the original, is still most of half an hour longer than it has any good reason for being. Miles Malleson and Lajos Berger also display a marked inattention to detail in their writing, which is all the more noticeable in contrast to the meticulous care that went into the filmís imagery; their giddy disregard for basic geography is just one especially noteworthy example. Conrad Veidt gives a serviceable performance as Jafar, but it is jarring in the extreme to hear an Arabian sorcerer speaking with a pronounced German accent. Meanwhile, the rest of the cast doesnít so much act as put on a thespian strongman show, struggling and straining to lift their impossibly ďdignifiedĒ dialogue. Finally, you have to marvel at the casting of the two heroes. Douglas Fairbanks didnít exactly win accolades from me in the previous version, but thereís no denying that he was damned impressive in a sword fight. John Justin, on the other hand, would be right at home in the Sultan of Basraís collection of automata, and Sabu makes about as convincing a swashbuckling hero as would Alfalfa from the Little Rascals. I donít care how many genies and flying carpets and magic crossbows with injustice-seeking quarrels they have to back them upó these two guys are not taking down any evil magicians, and not even the finest special effects will persuade me otherwise.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact