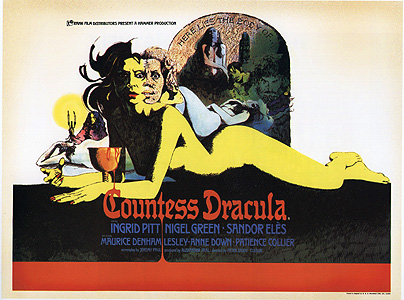

Countess Dracula (1970/1972) ***

Countess Dracula (1970/1972) ***

You know how it goes with family reputations. For generations, a name is loved and respected throughout the land, then along comes one asshole, and the next thing you know, all the grandkids are running around saying, “No, no— it’s ‘Fronkensteen.’ Seriously!” So pity the poor Bathorys. Their lineage included generals, jurists, palatines of Hungary, voivods of Transylvania, rebels against Habsburg tyranny— even a cardinal and a king of Poland! But which Bathory does the world outside of Hungary remember? Just that psycho Countess Erzsebet, from the junior Ecsed branch of the family. And really, can anyone blame us? I’d have to walk you through centuries of unfamiliar history to explain why you should give a crap about Gabor Bathory or Count György VI, but for Erzsebet, all I need to say is, “She tortured 600 girls to death, and bathed in their blood to keep herself looking young and sexy.”

In truth, though, it might not have been 600 girls, and she almost certainly never bathed in anybody’s blood, but you know how it goes with this stuff, too. Once somebody acquires renown as a truly extravagant human monster, people become willing to believe anything bad that they hear about them. Think of Ilse Koch and her Gypsy-skin lampshades. Yes, they were really goatskin, and no, the patterns on them weren’t really tattoos, but this is a woman the Nazis brought up on charges of excessive cruelty to prisoners. The idea that she’d have inmates at Buchenwald skinned for their tattoos is much easier to swallow than the idea that some misdeeds were beyond even her limits. Erzsebet Bathory, likewise, was convicted of 80 murders by the court that tried her in absentia on January 7th, 1611. The larger, more famous figure corresponds to the number of names listed in one of the exhibits entered into evidence against her, a book which some witnesses claimed was the countess’s torture diary. Apparently the judges were not persuaded of the ledger’s significance, but even the official tally would make Countess Bathory the deadliest female serial killer known to history. Her methodology, meanwhile, was more than ghastly enough even without positing some sorcerous after-the-fact use for all the blood she and her four servant accomplices spilled. Erzsebet would recruit teenage girls from the villages on her and her husband’s considerable estates to become handmaids at one or the other of her castles. Then she would invent pretexts on which to punish them atrociously. Her victims would be flogged with whips, burned with iron implements, lacerated and maimed with shears or razors, turned into human pincushions. In the winter, Erzsebet might have a girl tossed out naked into the snow and doused with water until she was encased in ice; in the summer, a full-body honey bath and the local insect population would produce an equivalent effect. Sometimes, the infliction of suffering would bring the countess to such a pitch of ecstasy that she would lay down her instruments of torment, and set to work with her teeth and fingernails instead. Mostly, though, Erzsebet preferred to look on while her most trusted servants beat a restrained girl to death with clubs, endeavoring along the way to produce controlled patterns of bruises and swelling— then she would slit open the swollen areas to release fountains of blood and lymph. If anything, reinterpreting her crimes as Satanic rituals diminishes their horror; an evil enchantress in quest of immortality has a motive that one needn’t be a psychopath to understand!

The very brazenness and barbarism of Countess Bathory’s methods raises two obvious questions. First, how did she get away with it for so long? How the hell can someone spend virtually her whole adult life hiring the daughters of her tenants for jobs at her home, and then killing them sadistically without anybody getting wise to her scheme? And second, if Erzsebet was slippery enough to stretch out her killing spree for as long as she did, then how did she finally get caught? The answer to question #1 is complex. To begin with, the 16th and 17th centuries were an era of almost constant warfare in eastern Europe, as the seemingly invincible Ottoman Turks relentlessly expanded their empire toward the northwest at the expense of Christendom. Erzsebet’s husband, Count Ferenc Nadasdy (that was his maiden name, so to speak; the Bathorys were the more prestigious family, so Ferenc took the unusual step of adopting his wife’s surname after the wedding), was one of the great Turk-fighters of the age. He was given the equivalent of a generalship in 1578 (at the ripe old age of nineteen!), and from then until his death under somewhat mysterious circumstances in 1604, he was away on campaign more often than not. Erzsebet therefore had the castles to herself for months at a time, subject to no will save her own. Obviously that principle applied even more forcefully after Ferenc died, leaving her to rule the estates of the Nadasdy and Bathory families in her own right. The only people outside her inner circle, then, who were in a position to see what she was up to were the friends and relatives of her victims, and those folks, legally speaking, were virtually her property anyway. Besides, the rank of the Bathorys was such that she was officially immune from ordinary prosecution. It would have taken a special royal decree to bring the countess to justice— as in fact it did when the law finally came down on her, which brings me back to our second question.

In all probability, Erzsebet could have gone on terrorizing her domains for the rest of her natural life had she not succumbed to the urge to take her game up a notch. As the 16th century gave way to the 17th, Countess Bathory began taking in the daughters of the petty gentry, ostensibly to educate them in the intricacies of courtly etiquette. Naturally, however, the main thing to get finished at her finishing school was the lives of the pupils. A few dead peasant girls (or indeed a few hundred) were one thing, but not even a niece of the king of Poland could get away with murdering knights’ daughters as a way to unwind. A Lutheran minister by the name of Istvan Magyari caught wind of the hideous rumors surrounding the countess in 1602, and his calls for an investigation eventually reached all the way to Vienna. In 1610, King Matthias dispatched György Thurzó, the palatine of Hungary, to look into the matter, and the end came swiftly after that. Erzsebet’s accomplices, who were not high nobility, were executed with full medieval brutality (the Middle Ages lasted considerably longer on that side of the continent, in spirit if not as a matter of historical terminology), but Matthias was leery of establishing a precedent by granting a warrant for the countess’s head. Instead, she was walled up in her bedroom suite at Castle Csejte, where she lived out her remaining three years. Her property was confiscated by the crown, and her descendants banished from Hungary.

So where do the bloodbaths and black magic and so forth come in? To some extent, we need look no further than the trial records. This being both 1611 and one of the less enlightened corners of Europe, it was probably inevitable that charges of witchcraft and demonolatry would be leveled against a powerful, educated (Erzsebet read and wrote four languages fluently, even as her husband couldn’t so much as sign his own name), and manifestly evil woman, and at least one of the witnesses claimed to have seen the countess in sexual congress with Satan. (If said witness is to be believed, the Devil’s cock is huge— but I’m sure you could have guessed that on your own.) Others reported that Erzsebet drained the blood of her victims for use in alchemical experiments or diabolical conjuring. But not one of the 300 people who testified against Countess Bathory said anything about her bathing in blood to preserve her youth and beauty, or for any other reason. The earliest surviving mention of the practice for which Erzsebet is best remembered today came in 1729, in a book by László Turóczi. That was more than 100 years after her death, at a time when all official documents relating to the trial were lost. (They would turn up again in 1765, and receive publication in 1817.) It isn’t clear what Turóczi’s sources were, but it’s a safe bet that he relied heavily on oral traditions from the region of what is now Slovakia that surrounds Castle Csejte. Understandably, Erzsebet Bathory was not a popular woman in those parts; the family had her buried back at the ancestral homestead in Ecsed for fear that her grave might otherwise be violated, and to this day the country people of her former Slovakian estates remember her as “the Hungarian Whore.” In any case, it was Turóczi’s version that caught on, and subsequent writers were quick to link Countess Bathory with the lore of vampirism. It is as a vampire of sorts that she has left her most lasting mark on popular culture, too, so much so that the true story of a brilliant, headstrong, and immensely powerful woman who was also one of the greatest fiends in the annals of crime has been almost totally eclipsed. Certainly I’ve never heard of a movie that contented itself with the tale of the historical Erzsebet Bathory. Indeed, the earliest film I’m aware of to invoke the Blood Countess at all goes so far as to deny her her proper name in the title, calling itself not Countess Bathory, but Countess Dracula.

It’s curious, then, that Countess Dracula should begin on a historically accurate note, with the funeral of Count Ferenc Nadasdy, so called. (Incidentally, it will be a persistent source of minor amusement throughout the film hearing all these British actors grapple with the pronunciation of Hungarian names. Still, they rise to the challenge far more ably than a typical American cast of 1970 probably would have.) Not to worry, though— fiction asserts itself at the reading of the will, when the dead count’s aged widow, Elizabeth (Ingrid Pitt, of The Asylum and The Vampire Lovers) is required to make an even split of the estate with her adolescent daughter, Ilona (Leslie-Anne Down, of Hell House Girls and From Beyond the Grave). Now it isn’t that Elizabeth has anything against her daughter. The only reason the girl’s lived in Vienna most of her life is that her parents wanted to keep her far out of the sultan’s reach. It’s just that Elizabeth was expecting to be undisputed mistress of the Nadasdy lands, not to hold half of them in trust for Ilona. Nor is Elizabeth the only one of the interested parties to be left in something gallingly close to the lurch. Master Fabio (Maurice Denham, from Paranoiac and Hysteria), the count’s pet scholar, is content with his bequest of the contents of the castle library. Imre Toth (Sandor Eles, of 1000 Convicts and a Woman and The Evil of Frankenstein) is pleased enough to inherit the count’s stables and horses. As a soldier in the ongoing wars against Turkey, that’s something he can really use, and his youth and modest rank are such that he could scarcely have expected more, however high the esteem in which Count Ferenc held his father. But Captain Dobi (Nigel Green, from Corridors of Blood and Gawain and the Green Knight) has a real beef with his departed lord. Dobi was Count Nadasdy’s right-hand man for decades— to inherit no more than his master’s arms and armor is an outright insult!

Dobi shouldn’t be surprised at the count’s stinginess. Elizabeth had been cheating on her husband with him for 20 years, and although Ferenc was sensible enough to recognize that his busy schedule of war-making left him in no position to put a stop to the affair, that didn’t mean he had to like it. The captain consoles himself with the assumption that the count’s death clears the way for him to marry Elizabeth, but the widow herself has other ideas now that she’s met Imre Toth. Now that might sound like a pipe dream on her part— the soldier is young enough to be her son, and she has aged about as gracefully as Keith Richards— but a strange bit of happenstance casts the situation in a very different light. The countess has a handmaid named Teri (Susan Brodrick, from Dr. Jekyll & Sister Hyde and Journey to Midnight), whom she is in the habit of casually abusing. On the night after the funeral, an altercation over some too-hot bathwater results in Elizabeth getting a splash of the girl’s blood on her face, and when the countess wipes it away, she is astonished to discover that the skin beneath has lost all its wrinkles. That’s the last anyone ever sees of Teri, and when Dobi calls on Elizabeth in the morning, he finds her miraculously transformed back into a woman of 30 (or as the script preposterously insists on maintaining, a girl of nineteen). Who’s too old for Imre Toth now, eh?

The remainder of the film focuses primarily on the romantic triangle made possible by Elizabeth’s unnatural restoration, and on the increasingly deadly game of chess into which her and Dobi’s relationship degenerates because of it. Imre, Master Fabio, Elizabeth’s longtime companion, Julie (Endless Night’s Patience Collier), and even Ilona get caught up in it, too, in one way or another. And of course there are the other girls whom the countess kills for their blood once it becomes apparent that the effects of her sanguinary baths last only for a few days. Dobi tries to persuade the countess to sequester herself when he realizes what she’s done, ostensibly to dodge the thousand awkward questions that are sure to arise when Ilona returns from Vienna in a day or two, but really to keep her and Imre apart. Instead, she orders Ilona kidnapped and held captive in the cottage of a mute gamekeeper (Taste the Blood of Dracula’s Peter May), then presents herself to Toth as her own daughter at dinner that night. Elizabeth exploits the bonds of friendship to make Julie her procurer, then relies upon the woman’s fear of official punishment to keep her cooperating even after her conscience rises in revolt. Dobi’s ingenious-seeming scheme to split up Imre and Elizabeth by arranging for her to see him in bed with the village strumpet (Andrea Lawrence, of I’m Not Feeling Myself Tonight and Frankenstein and the Monster from Hell) backfires when the girl in question storms out in disgust over Toth’s lack of interest in anyone but the false Ilona. The captain’s machinations are exposed, Imre’s loyalty is affirmed, and poor Ziva winds up providing Elizabeth’s next bath. Master Fabio, meanwhile, overhears much more than anyone intends, and draws the logical deductions about what’s going on behind the closed doors of his lady’s suite. But what looks like a gambit to blackmail the countess ends with him being blackmailed instead into using his arcane knowledge to help Elizabeth perfect her youth-preserving magic. Even Dobi’s last desperate bid to drive Toth away by revealing to him Elizabeth’s secret founders on a drastic overestimation of the young soldier’s character. As in the true story, it is the countess’s own overreach that proves her undoing, as her decision to use the increasingly inconvenient Ilona as her next blood donor springs the latch on a whole Pandora’s box of unforeseen consequences.

Countess Dracula suffers a bit from an overly deliberate pace, and rather a lot from the exquisite uselessness of Imre and Ilona, the nominal hero and heroine. Particularly as played by Sandor Eles, Toth is a flaccid nonentity, unimpressive in every way. That Ilona would fall for him when they finally meet is reasonable, I suppose, since she is both equally devoid of charm or merit and completely without romantic or sexual experience. But we’re also asked to believe that Elizabeth would throw over her illicit lover of 20 years for this guy, and that’s simply never plausible— not when the competition is Nigel Green in one of his best performances! Eles isn’t even better looking than Green, no matter how far apart their ages, and when you factor in the intangible elements of masculine charisma (the ones that made Sean Connery, for example, a sex symbol right up to the eve of his 70th birthday), there’s absolutely no contest. Furthermore, Imre exhibits in the end no trace of actual heroism. He ends the story as he began it, a moral weakling, a shitty judge of character, and a slave to his dick. It would be alright if Toth’s unfitness for the role of the hero were part of the point— after all, Hammer Film Productions had made fine use of compromised or ineffectual heroes before, most notably in The Curse of Frankenstein and Frankenstein Must Be Destroyed. Here, though, director Peter Sasdy doesn’t seem to be aware of anything amiss. “Of course Imre’s the hero!” Sasdy seems to say, “He’s young and pretty, and he’s got a moustache any Cuban baseball player would kill for!” As for Ilona, she succumbs utterly to the curse of the gothic horror heroine. At no point is she more than an object to be fought over, and most of the time, she isn’t even that. Whenever the camera returns to the gamekeeper’s cottage, you can just about count on thinking, “Oh, yeah— her! I forgot all about her…” What makes Ilona’s vacuity worthy of special censure is that it stands her in contrast to one of the most forceful female characters Hammer ever portrayed. Monster or not, Ingrid Pitt’s Countess Bathory is almost as hard to resist rooting for as Peter Cushing’s Baron Frankenstein.

And that brings me around to why I like Countess Dracula despite all the foregoing. This movie isn’t really about Imre or Ilona. It’s about Elizabeth and Dobi— about two strong-willed people who know exactly what they want, and who each mean to get it regardless of the cost to themselves or to anyone else. Pitt demonstrates in this movie why she, practically alone among Hammer’s starlets of the 70’s, remained someone whom horror fans wished to see perform long after they lost all interest in seeing her take off her clothes. She is, aptly, a commanding presence, and again like Cushing in his many turns as Victor Frankenstein, she is charismatic without ever being sympathetic. Pitt also reminds me a bit of Dyanne Thorne, in that her sex appeal in this role has little to do with allure, and everything to do with power. It’s never explicitly stated that Dobi’s attraction to Elizabeth stems from his recognition of her strength, ruthlessness, and other “manly” virtues, but the conclusion is difficult to avoid. In any case, he surely isn’t in it for her beauty, which is long gone when we are introduced to the couple. All around, it’s an interesting relationship, not least because it represents a nearly complete reversal of the usual gender roles. Like a stereotypical woman in thrall to a dashing bad boy, Dobi loves the countess for exactly those qualities that make her a menace, and that love enables her to abuse and exploit him with impunity. Meanwhile, she, like a stereotypical male heartbreaker, is in a fevered rush to trade him in for a newer model. Imre thus becomes equivalent to the familiar schoolgirl naif, and Dobi is forced to rely on “feminine” guile to sabotage his younger rival’s chances. The inversion is all the more engrossing, too, for the fact that it’s Nigel Green of all people— a former Hercules, for heaven’s sake!— playing the scheming, jilted “woman.” As I said before while disparaging Sandor Eles, Green here is as alpha as alpha-males come, but he’s no match for Ingrid Pitt in that department, just as Dobi is no match for Elizabeth. I love seeing a movie mount a standard story template upside down, and Countess Dracula unquestionably accomplishes that.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact