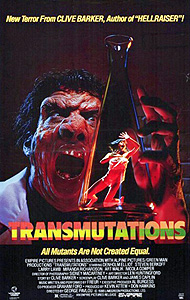

Transmutations/Underworld (1985) -**½

Transmutations/Underworld (1985) -**½

Two movies shot from scripts by Clive Barker came out prior to Hellraiser. One of them was among the most enjoyable man-in-a-suit monster movies of the 1980’s; the other one smells like feet. The dichotomy thus on display is brought into even sharper relief by the fact that both Rawhead Rex and Transmutations were directed by the same man, George Pavlou. The explanation, I think, is that the short story, “Rawhead Rex,” from which Barker adapted the former movie’s screenplay, could survive and in some ways even lent itself to misreading as a 50’s-style monster-rampage yarn, whereas Transmutations needed somebody who could get every one of its counterproductively many nuances exactly right. Pavlou was simply not that somebody.

At the London mansion where a glamorous old madam named Pepperdine (Ingrid Pitt, from Countess Dracula and The Vampire Lovers) maintains her high-priced brothel, Ricardo the doorman (Trevor Thomas, of Sheena and Inseminoid) turns away a would-be customer whom one assumes he regards as beneath the establishment’s usual standards. Meanwhile, Nicole (Nicola Cowper, from the 1989 version of Journey to the Center of the Earth), the whore whom the banished sleazebag had sought to hire, beds down alone in her room after injecting herself with a dose of some opaque, white fluid. This is apparently not quite what Pepperdine wants her to be doing right now, but either the madam is an extremely soft touch when it comes to stable discipline, or there’s something fishy going on here. I’m inclined to favor the latter interpretation, especially in light of the mob of masked weirdos loping through the streets toward the mansion like they’re on their way to a rumble with Pat Benetar’s backup band. The masked and leathered freaks scale the fire escape on the back wall of the mansion, at which point the brawniest of the bunch (Gary Olsen) forces the door into Nicole’s room. Ricardo comes running in response to the commotion, but there’s only one of him, and that’s at least three or four too few to stop the intruders from making off with Nicole. In fact, Ricardo would probably need that much backup just to come to grips with the big, door-forcing guy, who turns out to be… how shall I put this? How about “not exactly human?” Pepperdine’s bully-boy is just lucky the fanged, red-eyed mutant apparently has orders to cover his fellows’ retreat, and thus better things to do than stick around and finish breaking Ricardo’s neck.

The next morning, ex-gangster Roy Bain (Larry Lamb) receives a visit from an old colleague of his called Fluke (Art Malik) and a second man by the name of Darling (Brian Croucher). The mobsters are there on behalf of their boss, Hugo Motherskille (Steve Berkoff, of Prehistoric Women and A Clockwork Orange), who had been Bain’s boss, too, for a number of years. It looks as though Fluke isn’t authorized to say what it’s all about, but he does tell Bain that it concerns Nicole. Oh, really? That gets Bain’s grudging cooperation, and when he meets with his former employer a few hours later, it comes out that Motherskille not only knows about the abduction, but wants Bain to find the missing girl and perhaps rescue her should that prove both necessary and practicable. Why Bain, you ask? Partly because he’s predictably “the best,” but also because Motherskille knows that he had been in love with Nicole once. The gang lord figures that extra motivation will give Bain a crucial leg up on anyone else he might assign to do the job. Bain isn’t happy about it, but he doesn’t turn Motherskille down, either.

Roy’s visit to Pepperdine’s place is not very productive. Ricardo knows only that one of the kidnappers kicked his ass. Bianca the hooker (Irina Brook) knows even less than that. And while it’s obvious that Pepperdine herself knows or at least suspects a great deal more than she’s telling, she still isn’t telling any of it. The only real clue Bain comes away with is a vial of Nicole’s funny-looking drug, together with the information that she was probably getting it from somebody named Savary. Darling, too, makes the connection between Savary and the drug when Bain catches the henchman keeping tabs on him and gets up in his face about it, but much more interesting than either that confirmation or the attendant admission that Savary “makes things” for Motherskille is Darling’s reaction to the sight of the drug itself. He seems to attach an almost superstitious dread to the stuff.

Savary turns out to be Dr. Savary (Denholm Elliott, from To the Devil… a Daughter and The Vault of Horror), a medical researcher funded by Motherskille in his newly minted guise as an up-and-coming legitimate industrialist. Bain goes to see him at his clinic one night, and interrupts him in the process of giving an ominous-looking injection to a familiarly burly patient. Savary stonewalls Bain, but not at all convincingly. Then the sound of breaking windows intrudes itself upon their confrontation, and the doctor hurriedly excuses himself to deal with the mysterious emergency, admonishing Roy on his way out the door neither to leave the office nor to touch anything in it. Naturally, Bain rifles every drawer, shelf, and cubby-hole the second Savary is out of sight— not that he finds anything informative, though. When the doctor returns, he insists that their interview really must be at its end now, but Roy doesn’t need to see his adversary gathering up dozens of familiar vials from the floor in the room with the broken window to know that Savary is up to his neck in the weirdness attendant upon Nicole’s disappearance.

Speaking of Nicole, the next time we see her, she’s waking up in a makeshift-looking laboratory in what I take to be a converted utility tunnel beneath the city. Her captors are there, too, a tribe of hideously deformed men (plus at least one woman) led by a particularly lumpy-headed fellow who calls himself Nygaard (Paul Bowen, of Morons from Outer Space). Evidently these folks are all addicted to the same drug as Nicole (“white man,” they call it), which produces both intense euphoria and vivid hallucinations, but apparently also reshapes its users’ bodies in ways related to the content of those hallucinations. For example, Red Dog (that huge guy we keep running into) “dreams” of being some kind of powerful predator under the influence of the drug, so the side effects are turning him all Larry Talbot. The reason Nygaard and his people have kidnapped Nicole is that she seems curiously immune to white man’s mutagenic effects; the monster junkies hope to study her and figure out a way to reverse (or at least arrest) their own transformations. They also mean to use her as a hostage against Savary, who is evidently carrying some manner of torch for the whore. If they know about that (and if they feel in need of a hostage in the first place), then the addicts are obviously privy to a great deal more information about Savary than either we or Bain possess.

Bain will be finding out, though— both about the doctor’s secrets and about the underground monster colony. He’ll owe a lot of that learning to Bianca, who spies Fluke and Darling roughing up Pepperdine, and catches on that madam and gangsters alike are in on some sort of conspiracy related to her absent stable-mate. When she goes to Roy with the hints she has picked up, Bianca catches the eye of Red Dog, who has been roaming the streets, stoned out of his gourd on white man, since his escape from Savary’s clinic. Red Dog follows Bianca to Bain’s flat, and Bain in turn follows Red Dog to the entrance to the mutants’ lair after what certainly ought to have been a fatal gunshot to the chest makes the beast-man lose interest in raping his prey. Red Dog keeps dropping ampules of white man from his pockets as he runs, and that gets Roy thinking that another visit to Savary is in order. This time he hits paydirt, discovering the doctor’s video logs of experiments in which he tested white man (designed for use as a pain killer) on heroin addicts hired off the street. Savary is just as interested in Nicole’s immunity to the side effects as Nygaard, too, speculating that her making a living from realizing the fantasies of others somehow gives her a release valve for the psychosomatic mutations the drug causes in everybody else. Perhaps Roy can take that up with Nicole and Nygaard, in the event that he survives his second encounter with Savary to follow up on his earlier discovery of the monsters’ lair. The real question, though, is what Motherskille’s interest in all this is— and that’s a question Bain, Nygaard, Nicole, and Savary should all have started asking themselves a long time ago.

An investigation into a mysterious disappearance leads to the discovery of an underground nest of monsters who used to be street people… Sweet Jesus, this is Clive Barker’s C.H.U.D., isn’t it?! Transmutations doesn’t work anywhere near as well as that movie, though, again because it is fundamentally ill-suited to operating as a trashy popcorn creature flick. It attempts to tackle practically all of the recurring themes that Barker was working through in his fiction at the time: the weirdness hiding behind urban normality, the transformative power of fantasies, the equation of sex with magical or quasi-magical forces, the inescapable tendency of human beings to try to turn a buck on the numinous, and most conspicuously, the notion of a secret community of sympathetic monsters hiding in the shadows from a human world that would eagerly destroy them upon initial contact. Unfortunately, Barker was not up to such a wide-ranging synthesis at this early point in his career, to say nothing of George Pavlou’s limitations. Instead of a synthesis, then, Transmutations comes across as a mere pastiche of Barker’s various hobby-horses, dressed up in a form of stylistic excess that apes his without seeming to understand it. Few things could say more about how this movie goes wrong than the simple observation that the expected Barker foray into fetish eroticism comes here in the form of a tawdry, music video-like nightclub scene. Pavlou is trying, Hel bless him, but he just plain doesn’t get the material.

Having no money whatsoever to spend on anything didn’t help, either. Nygaard’s mutants are a markedly unimpressive lot, a far cry from the freak fantasias in which Barker’s fiction trades, or indeed even from the slightly clunky but at least suitably imaginative bestiary of Nightbreed four years later. There are too many tacky sets, too much TV talent in front of the camera, and very obviously not nearly enough time for anyone to really settle into their roles in the production. Transmutations is full of normally reliable third-tier actors putting in performances of which they should be deeply ashamed, struggling with characters who are either underconceived (Roy Bain being the foremost example) or overdone to the point of high camp (like Pepperdine and Motherskille). The “ain’t got time for quality” ethos is also reflected in things like the movie’s climax, in which it is possible to discern what Barker must have been aiming for in the screenplay, but only through a thick fog of half-measures and rushed approximations. To do that ending right would have required great planning and forethought, most significantly in the form of painstaking efforts to lay the necessary character groundwork in every scene featuring Nicole. Pavlou didn’t do that, though, and it’s an open question whether Nicola Cowper (whose main qualification for the part is that she looks cute in a fetish bridal gown) would have been equal to the task had he tried. So what ought to have been the payoff to all the eerie, half-glimpsed metaphysics that Pavlou was mostly in too big a hurry to deal with anyway winds up being just a half-assed retread of Scanners, by way of MTV. You can see why Barker would later insist upon directing Hellraiser himself with this serving as his introduction to the business of commercial filmmaking.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact