Sheena/Sheena, Queen of the Jungle (1984) -**

Sheena/Sheena, Queen of the Jungle (1984) -**

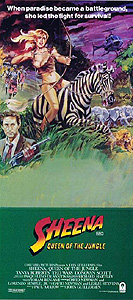

There are two traditional B-movie genres in which I have absolutely zero interest: westerns and jungle guy movies. There is no setting in all of history or mythology that I find less engaging than the Old West, and it doesn’t matter whether you want to call the jungle guy Tarzan, Jungle Jim, or Bomba the Jungle Boy— I still just can’t seem to give a fuck. Jungle girl movies, however, are another matter. Why, you ask? Okay, how about this— take a good, long look at the animal-skin bikini Tanya Roberts wears in Sheena/Sheena, Queen of the Jungle, and then reflect further on that question. If, after ten seconds of deep thought, you still can’t figure out why I would like jungle girl movies, even though I have no use whatsoever for the masculine version of the genre, you are obviously either (a) gay, (b) a eunuch, or (c) a Peter Cushing character. That said, I must admit that all jungle girl movies are by no means created equal, and that some of them are pretty rough going, even with all the vine-swinging upskirt shots and generalized T&A. And unfortunately, Sheena/Sheena, Queen of the Jungle is one of those films.

At bottom, lords and ladies of the jungle are just a special breed of superhero, and all superheroes need origin stories. Here’s Sheena’s: Once upon a time, a husband-and-wife team of scientists— and their blonde, preschool-age daughter— went to the jungles of the fictitious African nation of Tigora in order to investigate a legend the local tribesmen told about a mountain where the soil had mysterious healing powers. They arrived at the mountain just in time to witness the spectacle of a man whose body they knew to be riddled with malignant tumors being dug out of the “healing earth” with all his ills completely cured. Despite warnings from the shaman (Elizabeth of Toro) that the environs of the mountain were sacred ground, the scientists insisted on poking around in its caves, looking for anything that might explain the power of the healing earth. Inevitably, a spontaneous cave-in killed both investigators, leaving their young daughter to be raised by the shaman, who equally inevitably interpreted the girl’s arrival in light of an ancient prophecy foretelling the coming of a “golden girl” who would grow up to be the Zambuli tribe’s protector in a time of great peril. Twenty years later, Sheena (as the shaman has re-named the scientists’ daughter) has mastered the skills of archery, zebra equestrianism, and psychic communication with the beasts of the jungle and savanna, and looks to be well on her way to living up to that prophecy.

Back in the capital city of Tigora, the groundwork is being laid for that “time of peril” for Sheena’s adopted tribe. Vic Casey (Ted Wass) and his sidekick, Fletch (Donovan Scott, a minor master of bad 80’s comedy, who appeared in both Police Academy and Zorro, the Gay Blade— though he also showed up in Psycho III), are flying into Tigora to interview Prince Otwani (Trevor Thomas, from Inseminoid and Transmutations), the brother of King Jabalani (Clifton Jones, one of the voice actors from Watership Down, the grimmest, scariest, most depressing cartoon about bunnies ever made). Casey and Fletch work for some sports magazine or other, and their interest in Otwani stems from the fact that he supplements his princely income by playing NFL football— apparently, he’s quite good, too. What the journalists don’t realize is that Otwani is at the center a much bigger story than his prowess on the gridiron. He is conspiring with Princess Zanda (France Zobda), the king’s fiancee, to murder Jabalani and seize the throne of Tigora for himself. Not only that, he has learned from spectrographic analysis of satellite photos that a certain familiar mountain out in the jungle is sitting on top of a huge deposit of titanium ore. This incalculably valuable resource will remain unexploited as long as Otwani’s brother rules Tigora, though, because of Jabalani’s longtime friendship with the Zambuli; not only would the king never open that land up to titanium mining, he even allows the tribe to conduct its affairs completely free of interference from his government. Luckily for the conspirators, the Zambuli shaman is several steps ahead of them, and has come to the city to warn the king of their machinations. Why is this lucky, you ask? Because Otwani’s buddies on the police force pick her up first, opening up a priceless opportunity to frame her for the crime.

Otwani arranges to have a crossbow hidden in the boughs of a tree in the garden where the king plans to hold the reception dinner in honor of his brother’s stateside sports stardom. When the king stands to make his speech, that crossbow will fire an arrow of the distinctive design used by the Zambuli into his chest, and a moment later, the palace guards will “find” the shaman sneaking off into the night, carrying a bow. The assassination will turn public opinion against the Zambuli, and no one will complain when Otwani leases their land to a mining concern, and begins extracting the titanium buried under their sacred mountain.

The plan proceeds almost without a hitch. Jabalani dies, the shaman is thrown into prison, and the dollar signs start dancing in front of King Otwani’s eyes. But unbeknownst to Otwani, Fletch accidentally caught the crossbow’s firing on film, and when he and Vic Casey get a chance to look at their footage, they swiftly figure out what happened. Not only that, Sheena happens to have followed the shaman to town— how a half-naked, blonde, white girl riding a zebra and leading an elephant behind her managed to trek halfway across Tigora without anyone noticing is a mystery for greater minds than mine to solve. She and her elephant smash their way into the shaman’s prison cell on the very same night that Casey and Fletch had come to interview the captive woman, intent on clearing her of the old king’s murder. Thus it is that the journalists learn of Sheena, Queen of the Jungle, and thus it is that they embark on an adventure that will ultimately land them in more trouble than they ever thought possible.

While Casey and Fletch pursue Sheena and the shaman back into the bush, Otwani, Zanda, and a team of mercenaries under the command of the brutal Colonel Jorgensen (John Forgeham) set off in pursuit of them. The journalists catch up with their quarry first, and are thus able to warn Sheena (the shaman has by this time died from injuries inflicted on her by Otwani’s thuggish police) of the danger represented by the new king and his soldiers. After winning the jungle girl’s trust (and taking the first inevitable steps on the road toward getting into Sheena’s pants), Casey sends Fletch back to civilization with the incriminating film, while he and Sheena press on into the jungle to draw Otwani’s attention. Things really heat up when Jorgensen’s men massacre a village of defenseless natives; Sheena finally grasps the scale of the evil she’s up against, and realizes that she and her people will have to stand up and fight, rather than trying to get out of the way. And Otwani and his followers, for their parts, will learn just what a bad idea it is to pick a fight with a girl who can talk to rhinos.

It’s hard to believe a movie like this could be made without the involvement of Dino De Laurentiis, but that dreaded name is nowhere to be seen in Sheena’s credits. Then again, John Guillermin, who directed Sheena, also directed both the De Laurentiis King Kong and its even more abominable sequel, King Kong Lives. There is thus a very good reason for Sheena to feel like a De Laurentiis flick, even though it isn’t one. Guillermin obviously emerged from the experience of working with Dino with some degree of that man’s talent for blowing fantastic amounts of money on complete crap, because this is clearly one of the more expensive droppings to fall from the prolific rectum of Hollywood during the 1980’s. For one thing, the location shoots seem to have been spread all over Africa; admittedly, my grasp of that continent’s physical geography is a bit spotty, but I have a really hard time believing that all the radically different ecosystems we see over the course of Sheena’s wildly excessive 117 minutes could exist in very close proximity to each other. All that moving around has to have cost a fortune. Then there are the animal trainers’ salaries to consider— this movie features trained animals of no fewer than seven different species: chimps, lions, leopards, elephants, rhinos, hippos, and horses. (Note that there are no zebras in this movie, despite the fact that the script calls for Sheena to use one as her primary means of transportation. Zebras have resisted all our efforts to turn them into riding animals for at least 10,000 years, and so Guillermin was forced to make do with horses painted in fetching black and white stripes!) One place Guillermin certainly didn’t spend much money was in paying for his cast. It isn’t just that everyone here is a relative or complete unknown, it’s that they all suck to just about the maximum extent you’ll ever see in an expensive, mainstream-studio movie. Even the best of the bunch, Trevor Thomas, comes across as a sort of poor man’s O. J. Simpson, despite the fact that his earlier performance in Inseminoid showed that he can kind of act when he feels like it. As for Tanya Roberts, she got her starring role the old-fashioned way— she was fucking the director, and boy, does it ever show! Needless to say Sheena was not quite the golden ticket to stardom she was hoping for.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact