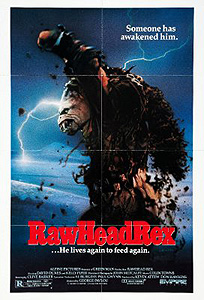

Rawhead Rex (1986) ***

Rawhead Rex (1986) ***

I can certainly understand Clive Barker’s objections to Rawhead Rex. If I had written the screenplay (or even just the source story), I’d probably be pretty pissed, too. There was some serious, thoughtful stuff in there, wedged in between the mutilations and beheadings and interspecies golden showers, and much as he had done the year before with Barker’s script for Transmutations, director George Pavlou failed to understand the meaning of any of it. But despite that writerly empathy, I am unable to join Barker in condemning the film. It may be light-years removed from the melding of pagan spirituality and extreme gore-horror that its author intended, but as a pure monster movie, unencumbered by Barker’s philosophical concerns, Rawhead Rex just flat-out fucking rocks.

American historian Howard Hallenbeck (David Dukes) has spent the last six weeks touring rural Ireland, together with his wife, Elaine (Kelly Piper), and their children, Robbie (Hugh O’Conor) and Minty (Cora Lunny). This is not merely a vacation for Howard— in fact, the wife and kids are growing increasingly restive about just how little resemblance to a vacation the trip thus far has borne. Hallenbeck is doing research for a monograph on the persistence of sacred sites through successive cultures, and he’s been visiting every boondocks church on the island looking for traces of pre-Christian (indeed, preferably Neolithic) worship on their grounds. He thinks he may have found the motherlode when he gets to the village of Rathmorne, and sees the church presided over by the Reverend Coot (Niall Toibin, from The Sleep of Death). Several of the standing stones in the churchyard are clearly not burial monuments, and the subject matter of the stained glass windows is decidedly odd. Most striking is the one that depicts some sort of monster-man— it doesn’t look a bit like the standard Medieval conception of the Devil— being somehow vanquished by a robed and hooded figure holding aloft an obscure object; the Latin inscription on the window reads, “Death goes in fear of that which he can never be.” Declan O’Brien the verger (Ronan Wilmot) is rude and standoffish when Howard approaches him about coming back in a day or two to look over the parish records, but Coot is both friendlier and more accommodating.

Meanwhile, on one of the farms surrounding Rathmorne, a trio of men attempting to clear a formerly fallow field for cultivation this season are having the damnedest time shifting a rock. More than an ordinary boulder, this is a pinnacle of stone that juts up some ten feet from the earth, as if it were giving heaven the finger. It must weigh several tons, and it’s no wonder that even with two steel pry-bars and a tractor, the farmers can’t seem to budge it. The sun is on its way down, a storm is blowing up from the east, and one of the men has a wife at home who’ll be pulling dinner out of the oven right about now. The farmer whose field it is grumbles a bit, but the time has clearly come to knock off for the day. However, after his friends have driven away, and while he is trying to wrench his pry-bars out from under the stone, something gives way beneath the ground. A fortuitous lightning strike (the monolith is easily the tallest thing for a mile or more in every direction) finishes the job, and the rock falls free with a great outpouring of noxious vapors from the cavity below it. Foul-smelling gasses aren’t all that’s been trapped under the rock, either, for a huge, shaggy humanoid lunges up from the hole, savages the farmer who unwittingly released him, and stomps off across the fields. The creature bears a notable resemblance to the one shown in Coot’s stained glass window.

The monster first reaches habitation shortly before dusk. He rests a bit in a stable, then kills the owner when he goes to investigate the appalling damage to the building’s door. The creature goes after that second victim’s pregnant wife, too, but strangely abandons the attack with her cornered literally within arm’s reach. To all outward appearances, there’s something about the pregnancy that the thing from under the stone doesn’t like, for he withdraws immediately after a swipe from his claws tears open the woman’s dress to expose her distended belly. Dragging the husband’s body along behind him, the monster retreats to the woods, where he sets up shop not far from a tiny trailer park, and panics the inhabitants by slaughtering a teenager in sight of his girlfriend and younger brother. Howard Hallenbeck catches a glimpse of Rathmorne’s unwanted visitor, too, while taking a late-night stroll.

The next morning, Inspector Isaac Gissing (Excalibur’s Niall O’Brien) and his police force thus have more blood-slathered crime scenes to clean up than they’ve probably had to deal with in their entire careers up to now. Small towns being the hotbeds of gossip that they are, it also doesn’t take long before Hallenbeck gets wise to what happened last night, and he decides that a visit to the police station is in order— while he has no real idea what he saw standing atop that hillock, he has an uneasy feeling that it has something to do with the three deaths. Gissing is not impressed with Hallenbeck’s report of an eight-foot ogre on the loose in his village, but his subordinate, Detective Larkin (Patrick Dawson), is somewhat less dismissive. Either way, Howard has told the police everything he can, so he goes on about his business, following through on his plan for a second visit to Coot’s church. It’s rather a washout. Coot regretfully informs Hallenbeck that the records he wanted to see have all disappeared, and O’Brien has grown hostile to the point of belligerence. The verger actually snatches Howard’s camera away and stomps it to pieces when he catches him taking pictures of the stained glass window depicting the monster. As you might guess, this is because the bloodthirsty creature has somehow gotten in psychic touch with O’Brien, filling his head with the idea that maybe he’s been working for the wrong god all this time. You see, that motif in the window is as pre-Christian as it looks, and once upon a time, Rawhead (as the monster was known back in the day— presumably a reference to the traditional Irish bogeyman Rawhead-and-Bloodybones) was an object of fearful worship in these parts, and now that he’s back in town, he has a renovation or two in mind for Coot’s church. Evidently he finds the altar displeasing in approximately the same way as that pregnant farm-woman’s belly. All that comes to light through a chain of events that kicks off with Hallenbeck’s second encounter with Rawhead, when the monster kills Robbie and absconds with his body. Even Gissing can’t brush that off, and soon every detective and constable in his employ is on the lookout for a huge, hairy beast-man. Rawhead, meanwhile, sets himself determinedly to repurposing that church, killing Coot and putting O’Brien to work removing and destroying anything inside that marks the site as consecrated to any other being. As for Hallenbeck, he catches on to the connection between Rawhead and the church, rightly concluding that whatever force defeated the monster the last time is still there, hidden someplace on the grounds. Perhaps it’s inside that altar Rawhead won’t go near?

The odd thing about Rawhead Rex is that Barker’s short story (and therefore presumably his script as well) is in here practically plot-point for plot-point, and yet the movie still manages to bear its source only the dimmest resemblance. Even the stuff you’d think couldn’t possibly fly in a commercial motion picture— the slaying of Robbie Hallenbeck, the scene in which Rawhead re-baptizes Declan O’Brien by pissing in his face while he kneels before the resurrected god-monster in the churchyard— made it in intact, but what’s missing is a sense of any given plot-point’s significance. In Pavlou’s hands, Rawhead kills people and knocks over trailer homes and pisses on vergers because he’s a great big monster, and that’s just the sort of thing great big monsters do. Declan O’Brien and Isaac Gissing wind up doing one degree or another of his bidding because he has powers of mind-control— at least whenever he remembers to use them. The monster is able to kill Reverend Coot in his own church despite an application of heavy-gauge holiness because it’s totally boss when a monster yanks a cross out of a clergyman’s hand and makes with the whoop-ass. No, no, and no! The key point is that Rawhead is neither simply a monster nor a demon in the Christian sense. He is supposed to be a pagan godling— specifically, an embodiment of the male principle run amok in its most primal form. Understand that, and every bizarre, seemingly unmotivated or unexplained thing in this story falls into place. Christian religious magic fails to affect Rawhead not because he’s just that big a bad-ass, but because the Christian God represents merely a more evolved and civilized form of the same cosmic force. They don’t call him God the Father for nothing, after all. Similarly, Rawhead is able to work his will upon O’Brien and Gissing because they are both figures of patriarchal authority, and were therefore plugged into his power to begin with, whether they realized it or not. To combat Rawhead, it is necessary to invoke the power of the female principle, over which he holds no sway— “Death goes in fear of that which he can never be,” and all that. Again, all the clues the viewer needs to put it together are present in the film, but Pavlou wanders heedlessly by every single one of them.

That leaves us with something along the lines of a From Hell It Came for the 80’s, and while that’s undeniably a lot less than what Rawhead Rex could have been, I can find very little fault with its performance in that mode. Rawhead himself is not quite as impressive as I’d have liked (strangely, the suit tends to look better in stills than it does in the movie itself— and I’ve seen stills in which it looks pretty sorry), but early in the film, when Pavlou can usually be trusted not to give us a better look at the monster than the special effects deserve, he conveys some degree of the necessary menace. There’s about as much gore and violence as could realistically be asked of a British horror movie two years after the rout of the Video Nasties, and as I’ve already mentioned, Pavlou was brave enough to keep some material that had “censor bait” written all over it. The pacing is much better than it had been in Transmutations, the screenplay is more focused, the acting is in most cases (by which I mean to exclude Ronan Wilmot’s portrayal of Declan O’Brien) another major step up, and in general, Rawhead Rex is just plain more professional than its predecessor. The most telling compliment I can give, I think, is to note that I first saw Rawhead Rex well before I had read the story on which it was based, and that it was only after I had the print version as a basis for comparison that I realized how seriously flawed the movie was.

Who doesn’t love a good, old-fashioned monster suit— or a shockingly God-awful one, either, for that matter? Certainly we B-Masters can hardly get enough of the things. Click the link below to join us in reveling over rubber-suit monsters fine and crappy, great and small:

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact