Hellraiser (1987) ***½

Hellraiser (1987) ***½

In 1987, a completely new development in horror cinema was long overdue. The slashers were wearing out their welcome, the zombies were (heh) dead on their feet, possession was passé, and after most of 60 years, it was getting harder and harder to think of new and interesting ways to approach the time-honored subjects of vampirism, lycanthropy, hauntings, and mad science. Luckily, 1987 was also when Clive Barker was at the height of his powers. Operating out of Liverpool, Barker was a novelist, a playwright, an artist, and a dabbler in filmmaking, but what he was first and foremost was an idea man of the macabre whose imagination was unequalled in his time except perhaps by David Cronenberg. I use that comparison advisedly, too, for like Cronenberg, the young Clive Barker exhibited a fascination with the dark side of sex which was almost monomaniacal. Barker also tapped into a powerful cultural current which was still primarily an underground phenomenon in the 1980’s, the glamour of freakishness and the drive of the inveterate outsider to mark him- or herself as permanently and indelibly as possible. In this age when body-piercing kiosks can be found in suburban shopping malls and Young Republicans unashamedly sport tattoos, it may be difficult to understand just how subversive Clive Barker seemed at the time, but back then, even mildly kinky sensuality was almost as much a taboo subject as it had been in the 1950’s. Indeed, it was just about the last of the old taboos still standing. Meanwhile, young people who committed even so small and reversible an act of rebellion against “good” taste as dyeing their hair green were practically begging for beat-downs from their peers and harassment from authority figures. The idea of walking around with a quarter-pound of surgical steel threaded through your flesh in assorted places both visible and concealed was just barely on the radar, and was the almost exclusive province of hardcore S&M freaks. So when Barker (until then a cult figure known mainly for his short fiction) took his first crack at directing a commercial feature film, the response was pronounced and instantaneous. To a degree that Barker, his cohorts, and the New World Pictures executives who were fronting the money had never dared anticipate, Hellraiser became one of the most phenomenal successes of its era. Indeed, it might not be going too far to speculate that its astonishing popularity played a role in the cultural sea-change that has left it looking slightly quaint some twenty years down the line.

Hellraiser was not quite Barker’s maiden voyage into film. He had made a few shorts during his student days (some of these unexpectedly saw release on home video during the 1990’s), and in 1985, he contributed screenplays to a pair of very low-budget horror movies called Transmutations and Rawhead Rex, the latter adapted from his short story of the same name. Barker was not at all happy with the way either of those films turned out, and the year afterwards, he got to work translating his newly published novella The Hellbound Heart into a movie script— and this time, he meant it to be his own ass in the director’s chair. He shopped the project around to a few independent studios, and eventually New World took the bait; in fact, they were so impressed that Barker was able to finagle small but significant budget increases out of them on two separate occasions during filming. It’s easy to see why, too. Though there are a few serious faults here and there, Hellraiser was so startlingly unique when it made its appearance that even audiences who were repelled by its exuberantly extreme gore often found themselves enthralled by it anyway.

World-traveling wastrel Frank Cotton (Sean Chapman, from Boarding School and Transmutations) meets with an elderly Chinese man to purchase a possession of his, an intricately constructed puzzle box of gold-inlaid hardwood. Considering the huge stack of $500 and $100 bills Cotton places on the table, it seems safe to say the artifact in question is more than just an ancient Oriental precursor to the Rubix Cube. It’s much more, as a matter of fact. Frank goes home after completing the purchase, at which point he sets about solving the puzzle while kneeling inside a perimeter of candles in an otherwise lightless room in his loft. We may plausibly infer that it comes as something of a surprise to Frank when he attains his goal, and his facial muscles are instantly skewered by barbed hooks which shoot out of the box on the ends of taut, iron chains. Cotton is soon joined by four leather-garbed figures with hideously and elaborately disfigured faces who proceed literally to disassemble him until nothing remains but a lake of blood and a scattering of gore-soaked gobbets of raw meat. The leader of these supernatural sadists (Doug Bradley, an old friend and colleague of Barker’s, who later appeared in Nightbreed and Killer Tongue) then returns the puzzle box to its original configuration, and he, his companions, their paraphernalia of pain, and the mortal remains of Frank Cotton vanish instantly into thin air.

Some time later, a man and a woman arrive at the same house with the intention of moving in. The man is Frank’s older brother, Larry (Andrew Robinson, of Child’s Play 3, who also played the serial killer in the original Dirty Harry), and the woman is his second wife, Julia (Clare Higgins). It seems the house had belonged to the Cotton boys’ grandmother, and has remained in the family as a sort of ancestral homestead, generally unoccupied but too densely crammed with memories for anyone to seriously consider selling it. And now that Larry and Julia are looking to make their escape from Brooklyn to someplace a bit more easygoing, it’s going to have long-term tenants for the first time in who knows how many years. Larry knows that Frank has used the old place as a bolt hole from time to time (in fact, there’s evidence in both the kitchen and one of the bedrooms that he did so as recently as a few months back), but since no one has heard from him in ages (Larry figures his brother is probably in prison somewhere) it doesn’t appear likely that there’ll be any trouble if Larry and Julia move in.

Julia doesn’t much like the house, though, especially once she finds a stash of old photographs depicting Frank in the company of a series of Southeast Asian hookers. Julia, you see, has a history with Frank, and it’s one which she’d really rather not be reminded of. Frank had stopped by Larry’s previous home a few years ago so as to attend his wedding to Julia, and almost immediately seduced the bride. Over the indeterminate span of time during which he stayed in the vicinity, Frank drew Julia into an increasingly torrid and sleazy affair before dropping out of sight as was his wont. Living in a place that will constantly remind Juila of Frank obviously isn’t going to be good for her marriage to Larry. For that matter, it probably won’t do the marriage much good, either, for the Cottons to live so close to Kirsty (Ashley Laurence, from Lurking Fear and Warlock III: End of Innocence), Larry’s college-age daughter from his previous marriage, who despises Julia and is despised by her in turn.

As it happens, neither one of those obstacles to the couple’s future happiness poses nearly as big a problem as the repercussions of a minor accident on moving day. Larry cuts his hand on a protruding nail while helping the movers haul the bed up the staircase to the third floor, and when he goes to Julia for aid and comfort (the sight of his own blood has always turned Larry to jelly), he bleeds all over the floor of the very room where, unbeknownst to either Larry or his wife, Frank met his appallingly grisly end. While Julia rushes her weenie-ass husband to the hospital to get some stitches put in, the floorboards soak up all the spilled blood in an unnaturally fast and efficient manner; as soon as this process is completed, a humanoid body begins to coalesce beneath the floorboards, clawing its way up into the room as it gains substance. Presumably if Larry had bled more, the thing from the floor might have made more progress, but as it is, the growth processes stop while it’s still little more than an oozing lump of gelatinous flesh that looks like a man and slithers like an eel (Tale of a Vampire’s Oliver Smith). Then that night, while Larry, Kirsty, Kirsty’s boyfriend (Robert Hines), and several of Larry’s tiresome friends are having a dinner party downstairs, Julia meets her grotesque new housemate, and learns that it is really the long-missing Frank. (The reason it’s a different actor underneath all the makeup is that Chapman would have looked too bulky inside the full-body appliances. All that foam latex brought the cadaverously skinny Smith up to just about Chapman’s build, and since both actors had their voices overdubbed by an American anyway, most viewers never noticed the substitution.) As he explains to Julia, his insatiable hunger for new experiences— especially new sensual experiences— eventually led him to seek out the Chinese man’s puzzle box, which was rumored to be the conduit through which humans might get in touch with the Cenobites, beings from another dimension who have dedicated themselves to the discovery of extraordinary, transcendent sensations. Frank was naïve enough to assume that the Cenobites’ definition of pleasure would be compatible with his own, but a short time in their company disabused him of that notion. Compared to the Cenobites, Donatien de Sade and Leopold von Sacher-Masoch were nothing but pusillanimous dilettantes, and the end result of Frank’s indoctrination into their way of doing things was that mess we saw back at the beginning of the film. Somehow, though, Frank was empowered to return to this world through the blood his brother dripped on the floorboards where he had died. And if Julia could find it in her heart to bring him more blood, he ought eventually to be restored completely, allowing the two of them to ditch boring old Larry and pick up their affair where they left off.

It doesn’t take long for Julia to make her decision. The next afternoon, she picks up a man at a bar, brings him back to the house, and beats him to death with a claw hammer after leading him into Frank’s room. It would appear that some kind of law of diminishing returns applies to Frank’s condition, however, for all the blood from the dead man’s body falls far short of effecting his full restoration. Julia must bring him more victims over the ensuing days, and her strange behavior while she struggles to reconcile herself to the idea of being a murderess brings Larry to suspect that something is going on behind his back. Larry talks Kirsty into acting as his eyes, and the girl comes over to the house one afternoon just as Julia is returning home with her latest offering to the monster in the attic. Kirsty’s first impulse is to leave and tell her father that he’s being cheated on, but then she hears the man Julia brought home screaming through the papered-over window beneath the gabled roof. She rushes into the house, where she soon has her own run-in with Frank, attracting his malevolent desire. Kirsty is able to escape only because she notices how protective Frank is toward the puzzle box; she snatches it up, lobs it through the window, and then takes advantage of Frank’s consternation to run out the door and retrieve it. She succumbs to shock and exertion some time later, and is packed off to the nearest hospital.

While Kirsty is recuperating, she makes the mistake of fiddling around with the box, and fortuitously stumbles upon the right combination of maneuvers to open it. Her first encounter is with a weird monster that resembles a cross between a dog, a scorpion, and a human fetus, but the Cenobites come for her soon enough. Evidently it doesn’t matter whether the box has been opened deliberately or by accident; once the puzzle has been solved and the Cenobites summoned, they cannot return to their own dimension without bringing someone from our world with them. Kirsty is a sharp girl, though, and she quickly figures out that this quartet of scarified fiends is somehow responsible for transforming Frank into the skinless vampire she saw back at her father’s house, and if that’s so, then it follows that Frank escaped from their clutches. Thinking quickly, Kirsty cuts a deal with the Cenobites: if they’ll let her go her way unmolested, she’ll lead them to Frank so that they can reclaim what is theirs.

Given that Hellraiser was both written and directed by the author of The Hellbound Heart, you’d expect it to follow its source material very closely. And while that’s true for the most part, there are a number of noteworthy differences between the print and celluloid versions of the story. As a general thing, I would say that the movie makes for a more compelling narrative, while the book is more satisfying from a metaphysical point of view. The main jumping-off point for The Hellbound Heart— that the Cenobites are not evil per se, but rather such perfect hedonists that their esthetic sensibility draws no distinction between pleasure and pain, and that by inflicting the sufferings of the damned on their victims, they are merely giving them what they thought they wanted— receives short shrift in Hellraiser, lurking between the lines of the screenplay instead of helping to drive it directly. Likewise, Frank Cotton’s reasons for seeking out the box are less explained than implied. On the other hand, by transforming Kirsty from a dowdy girl nursing a hopeless crush on her lifelong friend into Larry’s daughter from an earlier marriage, the movie puts the rivalry between her and Julia on a pleasingly unconventional footing, while simultaneously making Frank’s openly sexual interest in Kirsty that much more alarming.

What both versions share most conspicuously is that they’re rather too short for their own good. The Hellbound Heart feels hurried at 164 pages, and Hellraiser contains so much intellectually stimulating material that gets touched on briefly and then dropped without fanfare that it could easily have filled out a running time of two hours or more. It would have been desirable for the film to let us get to know Frank better before his disastrous session with the puzzle box, in order to establish firmly just what he hoped to attain by opening the thing. The movie would also benefit from a bit more discussion about who and what the Cenobites are. Though they receive relatively little screen time, the Cenobites are really the mainspring of the film, yet their significance as anything more than monsters falls almost totally by the wayside. Perhaps Barker thought the name alone contained sufficient clues to the nature of the Cenobites, but the word is little used outside of the Eastern Orthodox Church, and may viewers are likely to imagine that it was just something Barker made up. Greek Orthodox Christianity recognizes three distinct strains of monasticism, of which the cenobitic is the most commonly practiced today. A cenobite is simply a monk, in approximately the same sense of the term that is most familiar to Western Christians. In contrast to hermits (who devote themselves to the contemplation of God in solitary isolation) and idiorrhythmic monks (who live in loose-knit communes permitting a considerable degree of leeway regarding individual lifestyles), a cenobite lives in a monastic community in which all things are rigidly governed by the abbot, and in which all monastery property is held in common. Thus by calling Hellraiser’s otherworldly villains the Cenobites, Barker is implying that they are a religious order of sorts, and that their explorations into the most extreme realms of sensation are made in the pursuit of some warped conception of holiness. This is a potent idea, tying the Cenobites in with a notion of spirituality that can be found among primitive cultures the world over, and as such, it would have strengthened Hellraiser considerably if Barker had taken the time to develop it at least as fully as he did in The Hellbound Heart. Another of the story’s supernatural elements which could have stood a bit of expansion concerns the two non-Cenobite creatures which appear from time to time. One of these is the monster which Kirsty encounters immediately upon opening the box; the other is the World’s Creepiest Hobo (Frank Baker), who wanders around town spying on Kirsty, and who is eventually revealed to be some sort of demonic personage affiliated with the box, and by extension with the Cenobites. In the novella, there is a fifth Cenobite, an enigmatic figure known as the Engineer, who presumably invents the machinery of torture which his colleagues use in their rites. Are we to infer that either the dog-scorpion-baby monster or the World’s Creepiest Hobo is the Engineer? For that matter, might it be possible that both of them are avatars of the same being, be it the Engineer or some other thing which Barker thought of while writing the screen adaptation? On the basis of the film itself, there’s simply no way to tell.

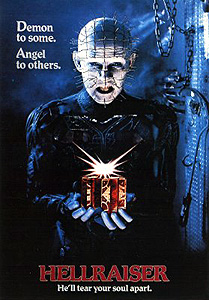

So far, it sounds like I’m denigrating Hellraiser, and I suppose I am a little. But I do so solely because so much of the movie is so goddamned brilliant that its shortcomings become all the more frustrating. At its heart, this is a horror film of ideas, which was an extraordinary rarity not just in those days of mass-produced slasher sequels, but in every period since the birth of cinema. Hellraiser posits more than just something awful running loose to do terrible things to the innocent. Like the writings of H. P. Lovecraft, it erects an entire cosmology of dread. Furthermore, it manages to combine that cosmic strain with a much more personal sort of horror, in the form of Julia’s conspiracy with Frank, and to maintain its seriousness even in the face of the most outrageously excessive graphic violence to be seen in a movie in many years. Finally, it introduced in the Cenobites— and in their leader especially— an icon of horror which seems likely to eclipse any of its contemporaries in the popular imagination, with the possible exception of Freddy Krueger. (As an aside, readers of The Hellbound Heart who saw the movie first may be surprised to discover that the Cenobite who most closely resembles the film’s Pinhead plays a minor role in the book, about on par with Grace Kirby’s female Cenobite. It occurs to me that Hellraiser might not have done nearly as well had Doug Bradley’s character been saddled with the uninspired look attributed to the lead Cenobite in the novel.) Any movie that can accomplish all that deserves a great deal of respect, even if it stumbles and fumbles a bit along the way.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact