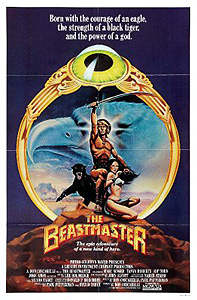

The Beastmaster (1982) **Ĺ

The Beastmaster (1982) **Ĺ

My family first subscribed to cable television sometime around 1982. This means that modern science has yet to devise a computer powerful enough to calculate the number of times that Iíve seen The Beastmaster. It also means that I have a much stronger affection for Don Coscarelliís contribution to the early 80ís barbarian boom than can possibly be justified on the merits of the film itself. Overlong, meandering, and often flagrantly silly, The Beastmaster nevertheless engages me to a degree that many much better 80ís fantasy movies are unable to match. A lot of it has to do with the way Coscarelli brings a distinct personal touch to what looks on its face like an exercise in pure moneygrubbing, but a lot of it is also because my brain spent so many hours soaking in this movie when I was a kid.

The Beastmasterís most immediately obvious handicap is one that it shares with a great many barbarian films, up to and including Conan the Barbarian itselfó the scope of its story is such as to require a prodigious amount of setup, and the payoffs that ultimately accrue from it all fall somewhat short of equivalency. Maax, the high priest of Ar (Rip Torn, from Coma and Slaughter), arrives at the ziggurat that dominates the city-state of Arak, and goes straight to the cellar to meet with his three pet witches (Janet DeMay, Janet Jones, and Christine Kellogg). The women inform Maax that Ar has favored them with a prophecy, and that things donít look good for him. Specifically, King Zed (Rod Loomis, of Girls Are for Loving and Jackís Back) and his wife (Vanna Bonta) are due to become parents any day now, and their son is destined to kill Maax. The high priest greets this pronouncement in the time-honored fashion, vowing to kill the unborn prince insteadó tonight, as a matter of fact, while thereís no chance whatsoever of the kid getting in the first shot. Just then, Zed himself bursts into the room accompanied by several soldiers. The king says heís heard tell that Maax has a child sacrifice scheduled, and he doesnít cotton to that sort of thing. Maax, displaying a flair for diplomacy that would have gotten him appointed American ambassador to the United Nations in later centuries, informs the king that not only is he fixing to sacrifice a child that night, but the kid in question is to be Zedís own unborn son. Zed understandably orders Maax banished at this point, but a fat lot of good it does him. That night, one of the witches sneaks into the royal bedchamber with a cow, and mojos the gestating prince out of the queenís uterus and into the animalís! Mom does not survive the transfer. Then the witch heads out into the countryside to perform the extremely rigmarole-intensive sacrifice. She is interrupted, however, by a passing traveler (Ben Hammer, from Invasion of the Bee Girls and Haunts), who is drawn to the scene when the slightly premature infant screams in response to being branded on the palm of the hand with the Seal of Ar. The traveler is a much bigger bad-ass than he looks, and while the witch puts up a pretty good fight, her magic is no match for a sword in the giblets. The man brings the rescued baby home with him to the village of Emer, where he proceeds to raise him as his own son.

As baby Dar grows first into Billy Jacoby (of Nightmares and Demonwarp) and then into Marc Singer (from V and Watchers II), he displays both a considerable affinity for swordsmanship and an uncanny ability to communicate with animals. One assumes the latter is an unintended side-effect of his having hitched a ride in the womb of a cow. Dad counsels him to keep quiet about the talking-to-animals business, but I think we all know how long thatís going to last in a movie called The Beastmaster. What finally gives Dar the impetus for trading in his life of peaceful subsistence-level farming for a new career of treading the earth beneath his sandaled feet and kicking the asses of everyone who gets in his way is an attack on the village by the Jun Horde. These guys are basically the Lord Humongousís army from The Road Warrior, reinterpreted for the dawn of the Iron Ageó their leader (Tony Epper) even wears much the same mask, although his version is painted black and has nifty sheet-metal bat-wings riveted to it. The Juns overrun Emer in minutes, killing literally everybody in town except for Dar (and even he gets wounded and knocked unconscious), and as the chaos begins to wind down, it becomes evident that the plundering nomads are in cahoots with Maax. As soon as Dar comes to and sees the smoldering ruins of his village, he swears revenge against the Juns.

I regret to inform you that we are still nowhere near getting into the meat of this story. First, we have to bring Dar into contact with his animal companions: Kodo and Podo the pants-stealing ferrets, a black tiger whose onomatopoeic name defies rendering in the Latin alphabet (itís an approximation of the animalís roar, and my best guess would be something like ďRrhŻhĒ), and a black eagle who wonít be getting a name at all until the much belated sequels. Then we have to introduce Dar to a temple slave-girl named Kiri (Tanya Roberts, of Sheena and Hearts and Armour, in a performance that almost makes it look like she can act), destined to be both his love-interest and his point of entry into the actual plot. Then we have to send him over to meet with Seth (John Amos, whose presence here goes some way toward explaining how he would later be reduced to movies like Hologram Man and Voodoo Moon) and Tal (Josh Milrad). Seth used to be King Zedís captain of the guard, but now that Maax has overthrown and imprisoned the king, heís something more in the line of a wandering freelance shit-kicker. He does aspire to restore the monarchy, though, and thatís where Tal comes inó the boy is Zedís son and, interestingly enough, Kiriís cousin as well. (Of course, that also makes him Darís [presumably half-] brother, but the Beastmaster never will get around to discovering his royal heritage.) And somewhere along the way, we have to squeeze in an encounter with a tribe of gargoyle-like creatures that eat humans by surrounding them in their wings and digesting them down to the bone, but who leave Dar in peace because his eagle reminds them of the god they worship. Only after all that does our hero finally set foot in Arak and the movie finally get down to business.

The first order of that business is to save a little girl from being sacrificed to Ar. Dar effects this by sending his eagle to snatch the victim from the pit of fire at the summit of Maaxís ziggurat, but because it just so happens that black eagles are considered the earthly avatar of Ar (ohÖ now I get itÖ), this performance doesnít have quite the intended impact upon Maaxís spiritual authority. The rescue does, however, win Dar a friend in town, in the form of Sacco (Ralph Strait, from Halloween III: Season of the Witch), the childís father. (Sadly, Sacco does not have a buddy named VanzettiÖ) And since Sacco owns a horse and a hay-wagon, his friendship could well come in handy for, say, smuggling Zed out of imprisonment. Then itís time to reunite with Seth and Tal to rescue Kiri from an execution of her own, and to free her from enslavement to the priests of Ar. All the commotion does make Maax rather curious about ďthis master of the beasts,Ē leading him to suspect that he may be dealing with that prince who was prophesied to kill him. The tyrant accordingly puts his two surviving witches in charge of finding and dispatching him, reasonably assuming that magic might succeed where the swords of his priests have thus far failed him.

One thing you can count on from Don Coscarelli. Whether they work or not, his movies are always at least a little more ambitious than the run-of-the-mill exploitation flick. Itís easy to see that there was a lot more to The Beastmaster than making a quick buck from the Conan afterglow, even though the cash-in motive is abundantly in evidence. If anything, The Beastmaster features far more good ideas than can be comfortably squeezed into even its considerable length, a surfeit that is lamentably paired with a budget that doesnít go quite far enough to get the job done. The unborn Darís mystical transference from his mother to the cow; the subhuman Death Guards that protect the interior of Maaxís temple; the character design for the witches, who are exquisitely beautiful from the collarbones down, but horribly decayed and disfigured from the neck up; the inscrutable, eagle-worshipping pterosaur peopleó these are all extremely cool touches, and more fantasy movies ought to be able to offer something like them. Coscarelliís use of the old-fashioned five-act story structure was a pretty ballsy move, too, but it unfortunately backfires rather seriously. First, it creates the illusion of a much slower pace than the movie actually keeps, in that a given amount of action will inevitably advance the plot proportionately less in a five-act script than in the more conventional three acts. Secondly, it invites the audience to wonder why the credits arenít rolling after the showdown between Dar and Maax, which, under the standard three-act paradigm, would naturally appear to be the climax. The Beastmasterís occasional admixture of humor into the action is a risk that paid off rather better. In contrast to the systemically campy barbarian movies that followed, The Beastmaster plays it perfectly straight for the most part, but there are a number of scenes that aim for a lighter tone. Some of them are genuinely amusing; others represent an unholy resurrection of 40ís-style comic relief. Together, they add up to a reasonably successful attempt to steer a middle course between Conan the Barbarian and The Sword and the Sorcerer. In short, although there are plenty of ways in which The Beastmaster doesnít quite come together, most of its failures are at least honest and earnest, the result of striving too hard instead of not caring enough.

There are, however, a few respects in which this movie is just plain sloppy. The mechanics of the Ar cult really donít bear much scrutiny. No reason at all is given for Kiri and the other slave-girls to be put to death, and when Dar, Seth, and Tal come to the rescue, you have to wonder just where in the hell all the slaves other than Kiri disappeared to. The connection between Maax and the Jun Horde is mysterious at best, and itís difficult to reconcile the nomadsí behavior during the climax with what we saw of them in the attack on Emer. On a related note, thereís some indication that Maax is doing the King Herod thing when he accompanies the Juns in sacking Darís village, but this potentially interesting plot development withers on the vine. The otherwise ingenious scene with Darís bovine surrogate mother is undermined when the camera closes in on the animalís underside, and we see that the cow is really a bull. Thereís also the bizarre continuity error on which the movie ends, to which the dialogue attracts the maximum possible attention. These foolish mistakes are frustrating, but the very fact that they stand out so glaringly emphasizes how hard Coscarelli was trying to elevate The Beastmaster above its natural level. In an Ator movie, for example, theyíd draw no special notice at all.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact