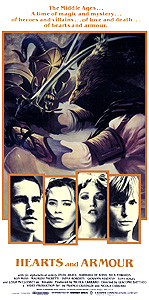

Hearts and Armour/I Paladini: Storia d’Armi e d’Amori (1983) -***

Hearts and Armour/I Paladini: Storia d’Armi e d’Amori (1983) -***

A funny thing about Excalibur: even though it was the proximate inspiration behind much of the 80’s sword-and-sorcery boom, I can think of only one film that directly and specifically rips it off. A truly remarkable rip-off Hearts and Armour (don’t blame me— that’s how it’s spelled on the video box) is, too, because its creators did nothing so simple as to shoot a cheap and silly version of the Arthurian legend and call it a day. Rather, director Giacomo Battiato and the usual Italian army of screenwriters applied the Excalibur treatment to a different centuries-old tale of chivalry, Ludovico Ariosto’s epic poem, Orlando Furioso. With a length in excess of 38,000 lines and a narrative scope to match, Orlando Furioso offers at least as great a challenge to would-be adaptors as Le Morte d’Arthur, and the makers of Hearts and Armour approached that challenge exactly the way John Boorman and Rospo Pallenberg did theirs— by blasting through edited highlights of the story at hypersonic speed, and sparing not a moment’s thought for whether or not the audience could keep up. Possibly that worked for Italian audiences, for whom Orlando Furioso might be as familiar as the legends of Camelot are to English-speakers. But for those same English-speakers, who generally don’t know anything about Ariosto’s work, Hearts and Armour is apt to seem a breathless exercise in scatterbrained confusion.

A maiden called Bradamante (Barbara De Rossi, of Sweets from a Stranger and Vampire in Venice) goes to see a witch (Lina Sastri) to have her fortune told. The witch prophesies that Bradamante will fall in love with a Moor by the unlikely name of Ruggero (The Boneyard Collection’s Ronn Moss) who is unfortunately destined to die by the hand of the paladin Orlando (Rick Edwards). (Orlando, by the way, is the Italian name for Charlemagne’s sidekick, Roland, as in The Song of Roland. That goes some way toward explaining why the character is referred to as “Rolando” in Hearts and Armour’s closing credits— but only some way.) The girl rides off then (no doubt regretting having asked about her future in the first place), only to be ambushed by a band of rapists in a narrow gorge. Bradamante is rescued, however, by a phantom knight who not only kicks her attackers’ asses, but then hands over to her his weapons and armor, promising that no harm will ever come to her while she is wearing and/or wielding them. She therefore does the only sensible thing at that point, and reinvents herself as a sort of Medieval Ms. .45, with the eventual result that she one day rescues a Moorish princess from the very same bunch of rapists, in the very same gorge. The Saracen girl bears the even more unlikely name of Angelica— except in the credits, where she’s called “Isabella” for some reason (and she’s played by the hilariously un-Moorish Tanya Roberts, from The Beastmaster and Tourist Trap). Not really knowing what else to do with her, Bradamante declares Angelica her captive, and continues her wandering with the princess in tow.

She’s still doing just that when she encounters the aforementioned Orlando and the Knights of the Silly Helmets. There are four of the latter: Rinaldo (Leigh McCloskey, of Inferno and Cameron’s Closet), who has a giant metal tulip atop his helmet; Selvaggio (Al Cliver, from House of Clocks and The Alcove), who has sheep’s horns on the sides of his; Aquilante (Lucien Bruchon, from Domino and Warrior of the Wasteland), whose helmet terminates in a sort of false cape that falls over his shoulders in the back like a giant steel mullet; and the hot-headed Ganelon (Giovanni Visentin, of The Killer Is Still Among Us and Flight from Paradise), who looks like somebody jammed a broadsword right down the middle of his Fissure of Rolando whenever he has his helmet on. Orlando, not to be outdone in this as in all things, has a lopsided halo of solar rays on his helm. Anyway, Ganelon challenges Bradamante (whose Egyptian sun-disc helmet is pretty silly, too, now that I think about it) to a duel the instant he lays eyes on her, leading to the inevitable “Ha-ha! You just got your ass whipped by a girl!” moment when she lifts her visor to reveal herself at the end of the fight. Bradamante of course recognizes Orlando from her vision in the witch’s cave, and she joins up with the knights, apparently on the theory that the best way to meet this Ruggero she’s supposed to fall in love with is to hang out with the guy who’s destined to kill him.

It’s not a bad strategy, actually. Back in what I assume to be Moorish Spain, the caliph has learned of Angelica’s capture, and he dispatches his bravest warrior— his son, Ruggero— to reclaim her from the heathen Christians. Ruggero’s fiancee, Marfisa (Zeudi Araya, from The Sinner and the Italian movie called The Prey, who as an Eritrean really could pass for Moorish), begs him not to go, but obviously that’s not happening. Sure enough, Ruggero’s expedition leads him into contact with the Knights of the Silly Helmets almost indecently fast, but because the Moor is just as chivalrous as his opponents, the encounter does not proceed directly to hacking and slashing. After some preliminary grandstanding on either side, it is decided that Ruggero will duel with one of the Christian knights at sunrise, with Angelica to be handed over to him without further ado if he wins. The Christians get to squabbling, though, over who will actually fight Ruggero— Orlando as leader of the party, or Bradamante as Angelica’s captor of record. Naturally, the true, unspoken point of contention is that Orlando won’t stand for a woman doing his job, while Bradamante won’t stand for Orlando killing Ruggero before she’s even had a chance to fall properly in love with him. And as if matters weren’t complicated enough already, Orlando and Angelica form an obviously foredoomed cross-cultural coupling of their own during the downtime before the contest for her freedom. Eventually, Ganelon decides that the whole argument over picking their champion is pointless, on the grounds that chivalry doesn’t apply to infidels. He storms off to murder Ruggero in his sleep. That brings him into conflict with Bradamante, of course, and Orlando gets involved a moment later out of revulsion at Ganelon attacking a woman in order to do something that was already shitty and dishonorable in its own right. Angelica takes the resulting internecine battle as her cue to sneak away, shanking Selvaggio to death when he catches on and tries to detain her. Naturally, everyone assumes that the killing and escape were somehow Ruggero’s doing once they finally settle down sufficiently to notice their comrade’s corpse, and the only reason the Moorish prince doesn’t get a four-on-one beat-down right then and there is because he mysteriously vanishes into thin air.

That would be the work of Atlante (Maurizio Nichetti). He’s a wizard, but closer to the Akiro end of the spectrum than the Merlin. Atlante can see the future, and for some reason, he’s very determined to prevent the rather futile bloodbath toward which the rest of the cast is racing. Above all, averting the carnage to come means keeping Ruggero and Bradamante apart, and the little magician transported the Saracen out of Orlando’s camp in the hope of talking some sense into him. Inevitably, that doesn’t accomplish much, not least because Bradamante is determined to seek out Ruggero, and keeps finding him no matter what tricks Atlante pulls.

Meanwhile, Angelica falls in with the screwiest-looking knight we’ve seen yet. His name is Ferrau (The Final Conflict’s Tony Vogel), and supposedly he’s a Moor. But whereas most of the Saracens we’ve seen thus far dress in loose, blue robes over linen jacks and leather breastplates, this guy has a full-body suit of steel plate and scale armor designed to make him look like a human raven. There’s a Trashmen joke I’d love to make right now, but it’s not really something that would work typed out. Whatever else Ferrau may be, he’s loony in love with the princess, and dedicates himself to seeing that she makes it home safely— or safe from everybody but himself, at any rate. Understandably, the pairing doesn’t last long before Angelica concludes that she’d rather take her chances on her own. All that goes on unbeknownst to the caliph, obviously, so when Ruggero fails to return with his sister after a reasonable interval, Dad calls in a trio of mercenaries fit for Skeletor’s army. Seriously, one of these guys (Bobby Rhodes, of Demons and Demons 2) looks like a Hyborian version of Baron Samedi, while another (Hal Yamanouchi, from The Sword of the Barbarians and After the Fall of New York) is apparently a samurai dressed up for Guy Fawkes Night. From this point on, Hearts and Armour possesses only the most tenuous sort of narrative structure, but the gist of things is that while the two pairs of star-crossed lovers try to figure out ways to cheat fate, the caliph’s mercenaries hunt down and kill the Knights of the Silly Helmets one at a time.

Many if not most online reviews of Hearts and Armour say that it was cut down from an Italian TV miniseries. I’m not sure I buy that, though, because the entire internet also seems to be in ignorance of any details regarding this supposed television version. Not only is it not commercially available so far as I can discern, but I can find no information about broadcast dates, number of episodes, original total running time, or other such basic characteristics. Nor, perhaps more importantly, can I find any description of what was cut out to make the familiar feature-length version. At this point, I have to wonder if maybe the widely accepted Hearts and Armour origin story isn’t just a case of speculation promoted to received wisdom. Certainly there’s no denying that this movie is jumbled and elliptical, that it has a habit of introducing characters only to kill them off immediately, that its resolution resolves very little, and that at no point is it very clear on why anybody is doing anything. A second movie’s worth of excised footage would indeed go a long way toward explaining all that. So, however, would the mere fact of trying to make a hundred-minute movie out of a 38,000-line epic.

Heaven knows the makers of Hearts and Armour left a bunch of stuff out. Don’t look for any sea monsters or hippogriffs here, let alone for any trips to the moon in Elijah’s flaming chariot to recover Orlando’s lost wits. In fact, don’t even both looking for Orlando to lose his wits in the first place. Of all the omissions, that’s the one I find the strangest. The reason why the poem is called Orlando Furioso— that is, Mad Orlando— is because its central plot thread concerns the insane rage into which Orlando falls when the pagan (not Muslim) princess Angelica does not return his love for her, and elopes to China with a Moor. Orlando’s madness provides a Grail-quest-like framework for vignettes in which Charlemagne’s other nights try to come up with ways to turn their berserk comrade back to normal. To make an Orlando Furioso movie in which Orlando remains sane throughout is a bit like filming Le Morte d’Arthur, but ending with the king still alive.

That, I think, is the most defensible reason for cutting Hearts and Armour so much less slack than Excalibur, even though the latter movie is arguably guilty of many of the same sins. Whatever crazy-ass shit John Boorman and Rospo Pallenberg got up to in their Medieval fantasy, it was always obvious that they understood and respected the source material, and had a legitimate rationale for their handling of it. It’s hard to extend Giacomo Battiato the benefit of the same doubt when Hearts and Armour removes the very spinal column of the story on which it’s based. Nor is that the only solid basis on which to disparage Hearts and Armour while defending Excalibur. Boorman cast his movie with seemingly every second- and third-string Shakespearean in the British Isles (a few of whom would become first-stringers in years to come); Battiato gives us Tanya Roberts and an American magazine-ad beefcake model. The weapons and armor made for the Knights of the Round Table by Terry English were anachronistic and slightly fanciful, but still looked sufficiently businesslike to be believable in most cases; in Hearts and Armour, it looks like English’s counterpart, Gregorio Simili, just got back from seeing Jabberwocky, and failed to understand that Terry Gilliam’s increasingly goofy parade of helm-top heraldic crests had been intended as a joke. Nichol Williamson’s Merlin, although certainly capable of clowning around, was nevertheless an unsettling, powerful presence; Atlante is nothing more than comic relief. Excalibur makes the most effective use of stock classical music since at least 2001: A Space Odyssey, and the original cues by Trevor Jones all riff intelligently on motifs in the borrowed pieces; Hearts and Armour’s score is magnificently wrong-headed, alternating between percussive electronic music better suited to a crummy post-apocalypse actioner and florid synth-and-woodwind stuff that suggests a down-market Sting wannabe. I could go on and on like this, really. It’s almost like comparing the two versions of The Wicker Man. The point, though, is that this is no brazen formal experiment that looks bad only until you realize that it’s playing by the rules of a different art form. Hearts and Armour is just a plain old lousy movie in the classic Italian style.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact