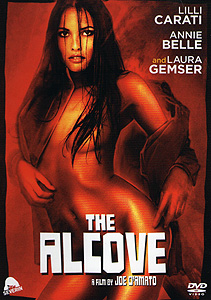

The Alcove/L’Alcova (1984) **½

The Alcove/L’Alcova (1984) **½

In my review of Papaya, Love Goddess of the Cannibals, I contended that the Third-World sexploitation movie was to Italian smut what the cannibal gut-muncher was to Italian horror, that both genres represented a sublimation (assuming it still counts as sublimation when the finished product is something so determinedly crass) of cultural unease related to the breakdown of colonialism. If that’s so, then The Alcove is the Cannibal Apocalypse of Third-World sexploitation, the film that brings the carnal dangers of the developing world home to “civilization” rather than sending its “civilized” protagonists out to face those dangers on their home turf. Its hero, if such he may be called, is an officer in Mussolini’s army who returns from the Ethiopian campaign with the daughter of an Abyssinian tribal chief, given to him as a slave by her father in return for saving his life. The Abyssinian girl herself eventually becomes the movie’s nominal villain, although by that point, it’s hard to work up much sympathy for either of the women who might qualify by contrast as its heroine.

The officer’s name is Elio Silvetri, and he’s played by Al Cliver (whom we’ve seen before in Devil Hunter, and will see again in Hearts and Armour). As he explains to his wife, Alessandra (Lilli Carati, from School Days and The Pleasure), when he returns home with Zerbal (Laura Gemser, of Taboo Island and Emanuelle, Queen of Sados) as a most unexpected souvenir of Ethiopia, his unit had just won a close-fought battle with the natives when he encountered a detachment of blackshirts unnecessarily roughing up some of the defeated Africans. Elio happened to outrank all of the offenders, and he was able to put a stop to it before anything really awful happened. One of the people on whose behalf Elio intervened was chieftain of the local tribe, and according to his people’s custom, he offered Elio his daughter in gratitude for the rescue. It would have been interpreted as a grave dishonor for Elio to turn the chief down, and thus the Silvetris now find themselves with a live-in servant with no grasp whatsoever of European folkways, and only the most limited command of their language. Alessandra is not pleased.

Even less pleased than Alessandra is Elio’s secretary, Velma (Annie Belle, from Annie and Forever Emmanuelle). Partly this is because Velma is even more horribly bigoted than Alessandra, but really her displeasure has less to do with Zerbal’s advent than with Elio’s return. She’d been having an affair with the lady of the house in her boss’s absence, and she reasonably calculates that she’ll be getting significantly less action now that Elio is readily at hand once again. The romantic situation at the Villa Silvetri rapidly moves beyond the merely triangular, though, when Elio has to go to his publisher’s offices in Rome in order to hand over what he’s completed of the manuscript for his memoirs of the Ethiopian campaign (the implication being that Elio has retired from the army, and wants a new source of income to cover the difference between his pension and his old active-duty salary). Zerbal immediately objects to being left behind, on the grounds that “the Scriptures” clearly dictate that she can have but one master (good luck reconciling this vague bullshit reference to the Koran with the later scene in which Zerbal is shown praying to her people’s vague bullshit moon goddess), leading Elio to try solving the problem by officially transferring ownership of her to Alessandra. This apparently requires an involved and frankly sexual ritual of submission, and although Alessandra makes a big show of discomfort while Zerbal is kissing and licking all over her body from the insteps up, it’s obvious enough that the sapphically inclined woman actually enjoys the experience quite a bit. Presumably that accounts for the rapidly increasing amount of attention that Alessandra lavishes upon Zerbal during her husband’s business trip, while the attention she pays to Velma declines commensurately. By the time Elio comes home again, Velma is so full of jealousy that she doesn’t know what to do with herself. Surprisingly enough, Elio has a similar reaction once he figures out what his wife is up to, even though he had already caught on to her and Velma and tacitly accepted their dalliance. His planned riposte is to cuckold Alessandra right back by taking her place in his secretary’s bed, but Velma herself is only grudgingly cooperative. At first, you’ll probably assume, as I did, that this is because Velma is strictly a lesbian, but such assumptions are undermined when Furio (Roberto Caruso, of The Church), Elio’s son from his first marriage (whose relationship with Alessandra has been and remains one of mutual antagonism), arrives on leave from the naval academy. The girl proves rather more receptive when he comes sniffing after her than she was toward his father’s advances. Not so receptive as to dispose of the issue, mind you, but receptive enough to raise questions about Velma’s sexuality, and to keep them in play until the closing credits. And also receptive enough, or so we may surmise, to hasten Alessandra’s transition from losing interest in Velma to actively wanting her gone, despite the secretary’s continued importance in Elio’s book project.

Things turn from complicated to ugly when a visit to the widow of a comrade-in-arms gives Elio the idea to go into the filmmaking business. The dead man had been a director back in silent-film days, and his wife was his favorite starlet. Significantly, most of their output had consisted of stag reels sold under the table to representatives of private gentlemen’s clubs and such, ranging from more or less era-appropriate nudie clips to totally anachronistic modern-style (except, obviously, for being silent and monochrome) hardcore porn. Elio gets it into his head that skin flicks featuring Alessandra, Velma, Zerbal, and the Silvetris’ brawny but rather strange-looking gardener (Nello Pazzafini, from Seven Bloodstained Orchids and Ator, the Fighting Eagle) could net him far more money than his war memoir (the writing of which is not progressing according to the publisher’s expectations), and he eventually manages to talk the girls into it. What Elio fails to recognize, however, is that Alessandra’s agreement stems wholly from the opportunity the porno shoot creates for humiliating Velma. All three women were supposed to wear identity-concealing domino masks during filming, but Alessandra makes sure that Velma’s face is exposed for a scene in which the latter is tied to a bed in the role of an accused heretic being sexually tortured by a randy nun and two fellow inquisitors. Alessandra hopes that by undermining the virginal façade that Velma presents to the world, she can sour Furio on her and chase her away from the villa in self-inflicted disgrace.

Meanwhile, in a subplot that comes straight out of the suburbs of nowhere, Zerbal starts doing some scheming of her own, looking to get back at the colonial oppressors she was palmed off on by her dad. To begin with, Elio’s first wife left behind a fortune in jewelry, and although Alessandra wears it as if it were her own, the lot of it is to be passed on to Furio as his inheritance. Zerbal thinks it should be hers instead. Also, Zerbal has lost her taste for the bottom end of the dominance dynamic, and the virtuosity with which she plucks and strums the female erogenous zones is such that Alessandra is actually okay with letting her be the mistress for a while. Now if you’re asking me, that’s the kind of thing that really ought to be set up well beforehand, but The Alcove is a Joe D’Amato movie, and the things one ought to do were frequently just a bit too much to ask of him. In any case, immediately upon formalizing the role-swap, Zerbal orders Alessandra to see to it that she winds up with the first Mrs. Silvetri’s jewels. Furthermore, she also commands the death of Velma, who she has in no way forgiven for her racism and xenophobia. Murder may be a tad further than Alessandra was prepared to go herself, but Zerbal’s demand does rather harmonize with her own aims. Of course, I’m sure Furio would have a thing or two to say about the idea if he ever found out what his stepmother and her imported girlfriend were plotting…

The Alcove was made during a curious and little-remembered phase of Joe D’Amato’s career. In the United States at least, D’Amato is best known for the movies he directed from the mid-1970’s through the early 1980’s, during which time he juggled horror and porn as adroitly as he ever did anything, and arguably contributed more than any other Italian filmmaker to blurring the distinction between the two genres (an endeavor that was taken up with equal fervor by Jesus Franco in Spain and Jean Rollin in France). Most of his fans in this country are also aware that D’Amato eventually dived headlong into hardcore smut every bit as unedifying as the shit you could have found in the curtained-off back room of your local mom-and-pop video store, back in the days when you still had one of those. In between those periods, though, D’Amato spent a few years basically being the poor man’s Tinto Brass, enjoying some of the biggest budgets of his career and devoting much of his energy to nominal sex films so arty that they almost turned into something else altogether. Something like whatever the hell The Alcove is, as you’ve surely gathered by now. This is one time when I can harp on the subtext of a soft-porn movie without feeling like a bullshit artist, for The Alcove would read more or less like a straight drama if all you had to go on were the screenplay. It’s a skin flick only because of the way the sex scenes are handled; put somebody other than Joe D’Amato at the helm, and this script could just as easily yield something suitable for the Sundance Channel. Naturally, that means The Alcove isn’t very successful when judged by smut standards. D’Amato lacks the Tinto Brass touch for injecting some thematic ambition into his porn without sacrificing titillation, and the setting has to be considered unfortunate— the 1940’s were almost as unsexy as they were unfunny. As an exploitationeer’s attempt to make a serious drama about bigotry and colonialism, however, The Alcove is perversely fascinating.

On a certain level, exploitation is an inherently reactionary artistic mode, for it plays upon the audience’s basest impulses and most irrational fears. But in another sense, exploitation is inherently progressive, because it breaks every rule it lays its hands on. A great exploitation filmmaker— a David Cronenberg, a George Romero, maybe even a Larry Cohen— can use that paradox to make the viewer examine their base and irrational side, exposing it for what it is. But in the hands of a conspicuously non-great director like D’Amato, the paradox is more likely to be left sitting there unresolved, if not indeed unconfronted. What that means for The Alcove is a great deal of disapproving emphasis on the white-supremacist attitudes of the Silvetris and their hangers-on, constantly juxtaposed with a treatment of Zerbal that subliminally supports those attitudes. We’re always encouraged to look down on the white characters for looking down on Zerbal, but the action of the film invariably reveals that every negative assessment they make of her is factually correct. She does speak their language poorly; she does know next to nothing of their ways, and fail to understand correctly what little she has absorbed; she does adhere to a religion and a moral code totally incompatible with those of her owners; and because she is also conniving, vengeful, and ultimately murderous, the judgements the whites make about her character are right on the money after all, regardless of whether or not those judgements were reached from a valid basis. The Alcove is thus intellectually self-defeating in the end, but in a way that inadvertently says a lot about what makes the problems it tries to address so intractable. As weird as this sounds, it sort of succeeds by failing.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact