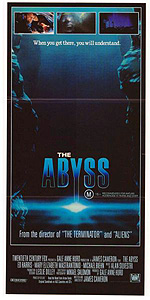

The Abyss (1989) **½

The Abyss (1989) **½

Some artists just plain need limits placed on them in order to work up to their abilities. For instance, in the mid-1980’s, when Guns ‘n’ Roses were just those guys who used to be in Hollywood Rose and the Fartz, they took a far-from-princely $75,000 advance from Geffen, and made the one hair metal album on Earth that’s even remotely worth listening to. Twenty years and more success than any five rock and roll sleazebags could take in stride later, the band has dwindled away to the Axl Rose Egomania Experience, and has spent more than half that time twiddling inconclusively with an album that still hasn’t quite managed to come out yet. Or how about Stephen King, who left his best work behind him almost exactly when he stopped submitting material to magazines, and when his hardcover publishers concluded that even an illustrated edition of a 1200-page door-stopper would make economic sense so long as his name was above the title. James Cameron falls into that category, too. His best movies, Aliens and The Terminator, were those on which the budgets, while certainly respectable, were not so vast that the occasional judgement call about where best to spend the money wasn’t necessary. Inevitably, however, their success put Cameron in a position to ask for more, and made the studios willing to give it to him. When that happened— for the first time on The Abyss— the judicious, disciplined touch he had exhibited before began to go soft, and his movies became increasingly unfocussed and ungainly. This is not to say that they turned bad, necessarily, but neither is The Abyss specifically any better than you’d expect from a hybrid of 2010, Close Encounters of the Third Kind, and The Poseidon Adventure in less distinguished hands.

The US Navy ballistic missile submarine USS Montana is out on routine patrol when its sonar picks up an extremely strange signal over what I take to be the Puerto Rican Trench. The hydrophone signature is plainly mechanical in origin, but there are none of the usual sounds made by a submarine underway— no cavitation, no engine noises, not even the characteristic churn of a screw propeller. It’s running extraordinarily deep for a military sub, thousands of feet down in the trench itself, and it’s moving at the astonishing rate of 60 knots. That’s half again as fast as the swiftest known submarine, and considerably in excess of what ought to be possible for an object the size of the unidentified vessel using any known underwater propulsion system. The captain orders the Montana down to have a look, at which point the mystery object switches to an intercept course and accelerates even further— first to 80 knots, and eventually all the way up to 120. The Montana’s sonar men never do get a clear impression of the bogey. It buzzes the sub at close range, and every device aboard goes haywire, sending the Montana on an uncontrollable crash-dive into the trench. All anyone can do is to deploy one of the sub’s distress buoys, and hope that someone spots it in time to effect a rescue.

Naturally, the necessary equipment for salvaging a submarine stranded halfway to the bottom of the deepest abyss in the Atlantic ocean is not something that just anyone is going to have. Certainly the navy has nothing of the kind, so when the Montana’s buoy is found by a Seahawk helicopter on a patrol of its own, the question becomes whom to hit up for favors. Interestingly, it happens that the Benthic Explorer, a research vessel belonging to an oil company that specializes in offshore drilling, is in the general neighborhood, testing out some of the snazziest deep-diving equipment in the world. The centerpiece of the operation is Deep Core 2, a mobile drilling rig designed to sink its wells directly from the seafloor, dispensing with the hundreds of feet of gantries required by conventional drilling platforms, avoiding the hazards of wind and waves, and offering the capability to exploit petroleum deposits far beyond the continental shelves. Associated with Deep Core 2 is a whole flotilla of advanced submersibles, both manned and unmanned, making the Deep Core project easily the best bet for reaching the Montana and rescuing whatever of its crew remains alive. Foreman Virgil “Bud” Brigman (Ed Harris, of Creepshow and Needful Things) is initially resistant to the idea (deep-sea salvage is hardly what his people are trained for), but when the rest of the crew have triple the usual dive-pay rate dangled in front of them, they unanimously overrule his objections. Nevertheless, when Deep Core mastermind Dr. Lindsey Brigman (Mary Elizabeth Mastrantonio)— Virgil’s estranged wife— flies in to stop the diversion of Deep Core 2 from its mission, the foreman is the one she blames for selling out. Dr. Brigman’s efforts come to naught, however, and before long, the Benthic Explorer and Deep Core 2 are both trundling along toward the Puerto Rican Trench. Unfortunately, Hurricane Frederick is headed that way, too, and seems likely to arrive well before the Montana’s would-be rescuers have concluded their business.

Naturally, no operation like this one would be allowed to proceed without some sort of military presence on the scene, and the navy sends along a quite formidable escort of destroyers, frigates, and (or so one assumes) attack submarines. They also send a three-man SEAL team, under the leadership of Lieutenant Hiram Coffey (Michael Biehn, from The Terminator and Grindhouse), to direct the salvage itself and see to the various national security niceties that must be observed in any situation involving 192 state-of-the-art nuclear warheads. Of course, the Cubans are not happy to see all of those American warships operating within cruise missile range of Havana, and within hours, there are reports of Soviet subs prowling the area. You might think a simple letter or phone call could clear things up, but consider it a little more carefully. Even if it didn’t run counter to 25 years’ worth of naval policy on operational secrecy, how reassuring would a telegram to Moscow saying, “It’s okay— one of our boomers went down around here, and we’re just trying to find the wreck,” really be? Meanwhile, tensions down below are running pretty high, too, because Coffey visibly has little faith in or patience for the civilians (Lindsey Brigman especially), while the aptly nicknamed Hippy Carney (Todd Graff, of Strange Days) just as openly believes the SEALs are up to no good. Then when Hurricane Frederick blows into town, the havoc the storm causes aboard the Benthic Explorer makes its way down the umbilicus to Deep Core 2, leaving the rig extensively flooded, incapable of surfacing, and with only twelve hours or so of breathable air. All in all, it’s an inauspicious backdrop against which to make first contact between humanity and an extraterrestrial intelligence.

Yeah, there are aliens down in that trench. They’re of the gentle and benevolent Spielbergian variety, but try telling that to Hiram Coffey. In fact, try telling Coffey that the strange, biological-looking machines sniffing around the wreck of the Montana and driving every electrical device aboard Deep Core 2 buggy while they do it are anything other than Soviet spy submarines. (Coffey’s determination to attribute everything the aliens do to the Cold War enemy eventually culminates in the movie’s most memorable and amusing line of dialogue: “Okay,” Lindsey Brigman asks after a particularly weird manifestation, “Who here thinks that was a Russian water tentacle?”) Dr. Brigman’s efforts to keep the situation on Deep Core 2 from turning ugly are further hampered when Coffey comes down with a bad case of high-pressure sensitivity disorder (apparently it’s kind of like rapture of the deep, except that it makes you psychotic instead of blissfully lethargic), and gets it into his head that circumstances warrant the early implementation of the SEALs’ secret protocol for keeping the Montana from falling into enemy hands. While Dr. Brigman brainstorms for ways to communicate with the aliens, Coffey and his men prepare to set off one of the submarine’s nearly 200 nukes, sacrificing, if need be, Deep Core 2 and the lives of everyone aboard it. Chances are that spacecraft at the bottom of the trench will be destroyed, too, if Coffey’s scheme comes to fruition, introducing the possibility of trading an international incident for an interplanetary one.

The most serious defect of The Abyss is that the Coffey situation is mostly resolved long before the end of the film, and when that happens, the Cold War tensions that have lurked behind everything in the movie up to then unaccountably vanish from consideration. Hurricane or no hurricane, renegade SEAL or no renegade SEAL, there’s still a major concentration of American military might within striking distance of Cuba, and an unknown but surely also significant concentration of Warsaw Pact forces eyeing the Americans nervously through their fire-control periscopes. Given the completely unexpected and completely impossible-to-ignore manner in which the aliens show their hands in the final act, you’d expect some kind of reaction from both sides. But apart from the one US destroyer we briefly glimpse at the very end, it’s as though the representatives of both superpowers greet Coffey’s exit (which they have no way of knowing about— hell, they have no way of knowing that the lieutenant went 50 kilotons’ worth of nutsoid on them in the first place) by saying, “Oh, good. I guess we can all go home now, eh?” It’s here that The Abyss most strongly resembles Close Encounters of the Third Kind, which also shat the bed in its closing phases by getting so caught up ooh-ing and ah-ing over the visitors from space as to lose track of the ramifications of everything that had happened before the mothership’s arrival.

That failure to keep the big picture in focus is a structural miscalculation as well as a lapse in story logic, because it removes all the urgency from the foreground plot at exactly the point when The Abyss ought to be gathering momentum for the home stretch. The villain has been eliminated and his plan thwarted, and now the only reason remaining for retrieving Coffey’s nuke is simple courtesy toward the aliens— the warhead isn’t time-fused, and with the remote trigger destroyed along with the submersible Coffey was piloting during his showdown with the Brigmans, there’s little chance of a spontaneous detonation. In order to generate any drama at all for the last quarter of the film, Cameron must take a page from Irwin Allen’s playbook of the damned by shifting the focus to a hackneyed peril-facilitated reconciliation between Virgil and Lindsey Brigman. And yes— there is indeed a tacky and manipulative CPR scene involved, concluding with enough tears of joy that it’s a wonder they don’t flood yet another of Deep Core 2’s compartments. The maudlin streak Cameron displayed here came as a most unwelcome surprise in 1989, but the advent of special-edition DVDs has revealed that his earlier movies escaped similar eruptions of schmaltz by only the narrowest of margins. Watch the conversation between Ripley and Burke regarding the former’s daughter in the “deleted scenes” section of the Aliens extras, and give thanks for the influence of parsimonious producers! The difference between Aliens and The Abyss in this respect is that the runaway success of the former movie led the studio to give Cameron a virtually blank check for the latter. Having no discipline imposed on him from without, Cameron was left to rely solely on his own internal discipline, and he seems to have found the temptation to self-indulgence irresistible. In fact, I wouldn’t be surprised if there were a bit of wish-fulfillment involved in the rise of the romantic subplot to dominance over the film, for Cameron and producer Gale Anne Hurd— his wife and creative partner of several years— were speeding toward divorce at the time The Abyss was in the works. Of course, just because it’s understandable that this stuff found its way into The Abyss, that doesn’t mean I don’t still wish it wasn’t there.

Materially, The Abyss is a much more impressive accomplishment. It represents an interesting stage in the evolution of modern special effects technique, in that it was among the first films to feature images that could never have been created without the aid of a computer, but was prevented by the vast cost of CGI in the late 1980’s from relying upon the new technology for more than a few eye-catching set-pieces. The Deep Core hardware, the aliens, and the aliens’ distinctively organic machines were all realized via practical effects, but the water-manipulation system used by the extraterrestrials required computer animation. It seems strange at first that these early experiments in CGI have aged so much better than similar sequences in movies only a few years old, but upon further reflection, it becomes clear that the makers of The Abyss, whether knowingly or not, chose CGI for exactly the sort of thing it excels at— creating images so totally impossible that the mind has no real-world standard against which to evaluate them. One can’t consciously or unconsciously notice flaws in the physics of water behaving like a flexible solid under the influence of a forcefield, for the simple reason that no one has ever really seen any such thing. Monetary considerations, meanwhile, ensured that The Abyss would depend for everything else on tried and true techniques that had reached what could plausibly be called the peak of their development, with much the result that you would expect.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact