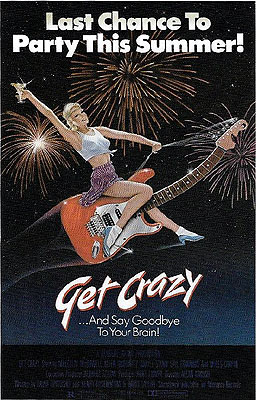

Get Crazy (1983) ***

Get Crazy (1983) ***

When Allan Arkush was in film school, he took a job as an usher at the Filmore East theater. Contrary to what you might naturally surmise from that sentence, the Filmore East didn’t show movies. Rather, in those pre-stadium days, it was New York City’s premier venue for rock concerts— which were something else that Arkush was passionate about. He stayed on for almost four years, working his way up through the backstage ranks until he’d been involved in most technical and logistical aspects of making shows at the Filmore East happen. And since the four years in question were 1968 through 1971, you have to know that Arkush saw some shit. On the stage during his tenure were virtually every significant rock-and-roller of the pot-and-paisley era, but that wasn’t the half of it. That lot’s offstage behavior was justly as legendary as their performances, and their audiences weren’t far behind them in picturesque debauchery. Arkush always thought there was a movie in his Filmore East experience somewhere, and one can easily see how it informed various films of his over the years, Rock ‘n’ Roll High School especially. It was only in 1983, though, with Get Crazy, that Arkush gave the subject the treatment it deserved.

Get Crazy is not officially a sequel to Rock ‘n’ Roll High School, but it feels like it takes place in the same universe. Like the earlier film, it plants its flag in a region where American comedy rarely ventured during its day, the zone where satire and free-wheeling absurdism meet. Get Crazy goes further, however, increasing the pace, the joke density, and the pitch of sheer zaniness to Zucker-Abrahams-Zucker levels. It’s also much edgier and more incisive about the things it makes fun of, and not all of its jokes are affectionate. I mention all this up front because this is one of those cases in which the viewer’s frame of mind going in is perhaps the critical factor determining what they’ll get out of the film.

Get Crazy’s stand-in for the Filmore East is the Saturn Theater, operated by Max Wolfe (Allen Goorwitz, from Sketches of a Strangler and Night Visitor). Max is one of those far-too-rare rock impresarios who manage to be wildly successful while still caring more about the music than the money. His nephew and heir, Sammy Fox (Miles Chapin, of Howard the Duck and The Funhouse), is a different story, however. He cares nothing at all for the Saturn’s place in music history, for his uncle’s legacy as a showman, or for the role of either man or venue in the community of rock and roll. To Sammy, the Saturn is just the building currently occupying an extremely desirable plot of Manhattan real estate, the lease to which he is due to inherit someday. Sammy even has a buyer in mind, however prematurely. Boorish, blond celebridouche Colin Beverly (Ed Begley Jr., from Dead of Night and Cat People), real estate mogul and owner of Serpent Sounds Promotions, has long had his eye on the Saturn’s block as a potential site for the crown jewel of his empire, a garish office tower to serve as the headquarters for his new Serpent Records venture, financed with shady money from Japan and Saudi Arabia. Max has kept Beverly at bay so far, no matter what incentives he and his sycophants (60’s pop crooners Bobby Sherman and Fabian Forte) offer up, but Sammy longs for the chance to be more accommodating. The constant pressure to sell out looks like it’s taking its toll, too, because Beverly’s latest visit works Max into such a rage that he gives himself what initially appears to be a heart attack.

Colin Beverly is the last thing that Max wants to be thinking about right now, because tonight is both New Year’s Eve and the Saturn Theater’s fifteenth anniversary. Wolfe has HUGE plans for the event, but is also under a commensurately huge amount of stress— which goes some way toward explaining what happened while he was throwing Beverly out of his theater. The talent Max has booked for the event covers as close as possible to the full history of the Saturn’s stage: King Blues, the king of the blues (jazz singer Bill Henderson, whose other acting credits include Trouble Man and Fear City); a currently hot post-punk art-rock act called Nada (led by Lori Eastside, then one of several vocalists associated with Kid Creole and the Coconuts); and British Invasion superstar of superstars, Reggie Wanker (Malcolm McDowell, from Tank Girl and A Clockwork Orange). Wolfe has an even bigger idea for a special surprise guest, too, although making it a reality will require some last-minute wheeling and dealing. Max wants to preside over the return to the stage of rock and roll’s reclusive poet laureate, Auden (Velvet Underground frontman Lou Reed), and such is his devotion to the cause that he’s even prepared to leverage his heart attack as a means of guilt-tripping the notoriously unreliable artist into performing.

Max’s heart attack is also battened onto by Sammy as his big chance to sell the Saturn’s lease out from under his uncle. He even goes so far as to sneak out of the theater for a private chat with Beverly aboard his helicopter. Having promised the scum magnate his uncle’s signature on a document transferring the lease, Sammy spends the next couple hours trying to get Max to sign it without looking at the text. Something always comes up, though, to take Wolfe’s attention away from the papers his nephew keeps waving in his face. Then Sammy receives news that completely changes the situation. That heart attack his uncle had? The doctor who comes to examine Max (Paul Bartell, of Chopping Mall and White Dog) declares it to be nothing more than an acute case of indigestion, brought on no doubt by the cruddy Chinese takeout he had for lunch. Max isn’t dying, and Sammy isn’t on the verge of inheriting shit.

Meanwhile, the Saturn staff, led by production manager Neil Allen (Daniel Stern, from C.H.U.D. and Leviathan), is scrambling to set up the unusually elaborate stage rig required by the New Year’s festivities. It isn’t going well, even after Neil’s predecessor, Willy Loman (Gail Edwards), joins in to help organize. Violetta the sound and lighting mistress (Mary Woronov, of Sugar Cookies and The Devil’s Rejects), for one, is about ready to strangle Joey (Wacko’s Dan Fischman), the most hapless of the stage hands. Luckily, Arthur (Tim Jones), a sound tech and aspiring drummer, says aloud what everyone is thinking, and wishes for “something that’s gonna blast us into the fast lane.” A second later, Electric Larry, the alien cyborg cowboy drug-pusher (tragically not credited), appears in a flash of sparks and smoke with a briefcase full of stimulants the likes of which are not often seen this side of Altair IV. After that, Neil and his crew are able to get the Saturn stage ready in no time at all. It’s a good thing, too, because Neil also has to face Connell O’Connell, the new fire marshal (Robert Picardo, from Jack’s Back and 976-EVIL). O’Connell is a stickling sort, and he makes clear that he’ll be keeping a very close watch over tonight’s show. The slightest hint of an open flame, and he’s shutting the place down.

That’s about when the bands start showing up— including one that isn’t even on the bill. You have to understand, though, that Captain Cloud (ex-Turtles singer Howard Kaylan) gets confused easily these days. He and his band, the Rainbow Telegraph, were booked to play the Saturn on 1968’s New Year’s Eve, and the time just sort of got away from them. Even so, Max is so happy to see them that he agrees to let them play the finale, after the ball drops in Times Square. Among the groups actually scheduled to perform, Nada arrives first, carrying their semi-feral but surprisingly astute business manager, Piggy (Fear frontman Lee Ving, whom we’ve seen before in Nightmares, and may see again someday in Grave Secrets), in the trunk of their car. Reggie Wanker makes it to the gig in one piece despite the best efforts of his maniacal drummer, Toad (Doors drummer John Densmore), who seizes control of Wanker’s private 747 over the North Atlantic. King Blues gets a late start on account of coming straight from the funeral of his longtime guitarist, Luther, but the dead man’s son, Cool (Queen of the Damned’s Franklyn Ajaye), manfully steps up to fill dad’s shoes and gets the boss to the Saturn on time (although King Blues’s antique Rolls Royce ends up somewhat the worse for the latter exertion). The only no-show is Auden, still ambling his way to the Saturn by taxi cab, having ordered the driver to take the scenic route so that he can compose his set for the gig on the way.

Of course, no one at the theater realizes what Auden is up to, and word of his last-minute addition to the program has reached the ears of Neil’s teenaged sister, Susie (Stacey Nelkin, from Halloween III: Season of the Witch). Susie wanted to go anyway, because she’s a huge Reggie Wanker fan, but Auden’s addition to the field makes this a can’t-miss-no-how concert for her. She therefore bamboozles her parents into believing that she’s going to a party at a friend’s house, and becomes one more thing for Neil to worry about amid all the rising chaos. Chaos like members of the audience sneaking in every imaginable form of weapon and pyrotechnic device, up to and including US Army-issue flamethrowers. Chaos like a man-sized anthropomorphic reefer, a shark prowling through the thigh-deep raw sewage in the men’s bathroom, and repeat visits from Electric Larry that leave each and every subset of the crowd well supplied with ever more exotic intoxicants. Chaos like Sammy mistakenly hiring a bar mitzvah band to back up King Blues. (“Man, I said I needed a blues band! You guys are giving me a Jews band!”) Chaos like the convoy of outlaw bikers who show up after the doors have been closed on account of the club having reached its official capacity, and who don’t intend to take “Sorry— no more room” for an answer. And most of all, chaos like Sammy’s increasingly desperate efforts to sabotage the Saturn’s fifteenth-anniversary extravaganza on behalf of Colin Beverly. Luckily, this is one of those nights when the problems all seem to solve each other, making for what might be the best Saturn Theater New Year’s Eve ever.

Allan Arkush once said of Get Crazy that it has 1500 jokes, but 2500 punchlines. That’s a fair enough description of this movie’s breathless approach to comedy. Half of the gags come completely out of nowhere, with neither setup nor follow-through, and although that does weaken a lot of them, Get Crazy spits out the jokes so fast that it can afford to waste material. Indeed, the story here is so slight despite its multiplicity of perspectives and subplots that I’m not sure it would work without the profligate artillery barrage of madcap humor accompanying it. Get Crazy’s dizzying joke density also serves a necessary narrative purpose, however, communicating for the benefit of those who’ve never experienced it some sense of the absurd scramble going on constantly behind the scenes at even a successful and well-managed rock club. I booked my share of shows during my 20-plus years of leading a gigging punk band, and although the details were of course very different at my level, I can assure you that this is exactly what it feels like. There are always a hundred developing calamities looming at the same time, the majority of them ranging somewhere between the ridiculous and the surreal. Oftentimes one calamity will have a growth spurt and crush you, but the really good, really successful, really rewarding shows are the ones in which you unaccountably manage to keep ahead of all of them until it’s time to send everybody home.

On a slightly more sophisticated level, Get Crazy is piled high with brilliant celebrity piss-takes, both loving and scathing (and occasionally both at the same time). It’s a hoot watching Lou Reed, Howard Kaylan, and John Densmore spoof Bob Dylan, Jerry Garcia, and Keith Moon respectively. Lee Ving is a delight as a human Chaos Muppet who is equal parts Iggy Pop, Sid Vicious, and himself. But the highest standard of celebrity caricature is set by Malcolm McDowell and Ed Begley Jr. I wish I knew more about New York City’s mainstream 80’s rock scene, because I can tell that the real-life inspiration behind Colin Beverly is hovering just beyond my mental reach. It’s plain enough that the formula is “what if Donald Trump and [Asshole X] were the same person?” but I have no idea who Asshole X could be. I have to assume that he was among the promoters who brought the depersonalizing, hyper-commodifying stadium concert model to the Big Apple, but beyond that it’s a complete mystery to me. In any case, Begley is titanically smarmy in the part, projecting a mixture of narcissism, buffoonery, and sociopathy that recent years have made hideously recognizable.

Malcolm McDowell’s Reggie Wanker is the show-stealer, though, not least because the filmmakers seem genuinely torn in their assessments of his real-world counterparts. I pluralize that because while Wanker is obviously inspired first and foremost by Mick Jagger, the details of both the character writing and McDowell’s performance are such as to make him a credible stand-in for any hero of the British Invasion who had descended into putrid self-parody by the early 80’s. Throughout the film, Wanker is made the butt of jokes in a way that isn’t really true of the other musicians, and he suffers losses, reverses, and humiliations of a sort that Get Crazy otherwise reserves for its villains. Witness, for example, the subplot in which his countess girlfriend (The Sword and the Sorcerer’s Anna Bjorn) becomes increasingly estranged from him, and ultimately finds satisfaction in the inexpert but eager arms of Joey the stagehand. But Reggie Wanker gets something that is denied to Sammy or Connell O’Connell, let alone Colin Beverley; he gets redemption. Mind you, Wanker’s redemption comes in the form of a commitment to sign over his management to his penis (which has become sentient and self-aware thanks to Electric Larry’s magic space acid), but redemption it is just the same. McDowell, meanwhile, endows the character with an affectedly antisocial, hormone-addled swagger matched only by his obliviously unearned self-pity. It’s as if McDowell is playing David Bowie playing Alex DeLarge playing Mick Jagger playing Hamlet, and it’s fucking brilliant.

Can you believe the B-Masters Cabal turns 20 this year? I sure don't think any of us can! Given the sheer unlikelihood of this event, we've decided to commemorate it with an entire year's worth of review roundtables— four in all. These are going to be a little different from our usual roundtables, however, because the thing we'll be celebrating is us. That is, we'll each be concentrating on the kind of coverage that's kept all of you coming back to our respective sites for all this time— and while we're at it, we'll be making a point of reviewing some films that we each would have thought we'd have gotten to a long time ago, had you asked us when we first started. This review belongs to the second roundtable, in which we each focus on those odd, dusty corners of the cinematic universe that have become our particular fixations. For me, that means the prehistory of the slasher film, 70's fadsploitation, the works of local antihero John Waters, and movies touching on musically-oriented countercultures, punk rock especially. Click the banner below to peruse the Cabal's combined offerings:

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact