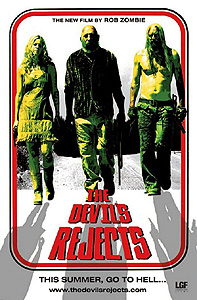

The Devilís Rejects (2005) **

The Devilís Rejects (2005) **

Now that he has a halfway substantial body of work to his credit (which is to say, five feature films and the fake trailer he contributed to Grindhouse), the consensus seems to be that The Devilís Rejects is the Rob Zombie movie to see, should you be determined to limit yourself to just one. Upon its release, nearly everybody I heard from hailed it as a significant improvement over House of 1000 Corpses, a far more mature and original picture than the aforementioned loving but haphazard grab-bag of 70ís horror cliches. Nevertheless, although a mature and original Rob Zombie movie remains something I would very much like to see, I considered it most unlikely that The Devilís Rejects would meet that description, for a variety of reasonsó not the least being Zombieís credit as screenwriter as well as director. I decided to wait for home video, and itís taken me this long to get around to it. Now that I have, it disheartens me to report that my suspicions of four years past are confirmed. The Devilís Rejects is no less a rip-off than its predecessor; itís merely less indiscriminate in its pilfering. Whereas House of 1000 Corpses fleshed out the skeleton of The Texas Chainsaw Massacre with organs and appendages swiped from seemingly every piece of trash celluloid that Zombie had ever seen, The Devilís Rejects is a nearly pure rehash of Arthur Pennís Bonnie and Clyde, except with the cartoonishness of the titular antiheroes amplified to Natural Born Killers proportions and the forces of law and order wearing the face of Dennis Hopperís deranged cop from The Texas Chainsaw Massacre 2.

Some five and a half months after the events of House of 1000 Corpses, Sheriff John Quincy Wydell (William Forsythe, from Savage Dawn and Hammerhead: Shark Frenzy) leads a massive police raid on the home of the Firefly clan. Tiny, the youngest of the boys (Matthew McGrory again, in a performance that he didnít live to see in its final, finished context), is out disposing of a victimís body at the time, but the rest of the family is drawn into a shootout that could almost pass for a military clash. Middle brother Rufus (Tyler Mane, of How to Make a Monster and The Scorpion King, taking over the role originated by Robert Allen Mukes) is killed in the fighting, and Mom (Leslie Easterbrook, from Dismembered and probably the least famous of the several horror movies called House, taking over for Karen Black) is captured by Wydell and his men. Otis (still Jim Moseley) and Baby (still Sheri Moon) escape through the drainage pipe that leads out from the basement to begin a new life as fugitives. Rob Zombie would like you to forget all about Tiny by the time act three rolls around, but donít you fall for it. Anyway, Otis and Babyís first thought is for their father, local Z-list celebrity Captain Spaulding (Sid Haig, who has fortunately not been replaced by somebody cheaper), whom they call at the shack where he lives with his grotesque sow of a girlfriend just as soon as they get far enough from the house not to have to worry about cops springing out from behind the nearest bit of underbrush. Wydell now has access to the clanís diaries and scrapbooks, you see, and Spaulding is incriminated by some of the material in them. Of course, Spaulding didnít make it this far in the serial murder business by leaving shit to chance, and heís long had a contingency plan for the event that he and his family would have to leave their respective homesteads and go on the lam. Spaulding has a buddy named Charles Altamont (Ken Foree, of The Dentist and Leatherface: The Texas Chainsaw Massacre III), who runs a whorehouse tucked away in the middle of nowhere with the aid of a slow-witted but dangerous-looking old man called Clevon (Michael Berryman, from The Hills Have Eyes and The Barbarians). Actually, Spaulding and Charles invariably refer to each other as brothers, but stand Sid Haig and Ken Foree up beside each other, and I think youíll agree that they almost have to mean that figuratively. In any case, the captain instructs his kids to meet him at the Kiki Palms Motel, from which point theyíll procure a vehicle that isnít registered to somebody known to be affiliated with them, and proceed on to Altamontís place.

The unfortunate owners of the vehicle on which Otis and Baby set their sights are a pair of country-gospel musicians named Adam Banjo (Lew Temple, of The Visitation and The Texas Chainsaw Massacre: The Beginning) and Roy Sullivan (Geoffrey Lewis, from Moon of the Wolf and Salemís Lot). Banjo and Sullivan are on tour with their wives, Wendy (Cutthroatís Kate Norby) and Gloria (Priscilla Barnes, from Trailer Park of Terror and Stepfather III), and a roadie by the name of Jimmy (Brian Posehn). Baby puts the moves on Roy (who isnít so married that he wonít think seriously about finding someplace private to spend an hour or two if the suggestion is put to him by a girl who looks like Sheri Moon) when she catches him out in the parking lot, and the next thing Roy knows, he, his partner, and their wives are all being held at gunpoint in their room by the fugitives, while Jimmy lies on the floor with a hole in his forehead and his brains spilling out onto the cheap and tacky carpet. Otis and Baby amuse themselves for a while by tormenting their hostages, but Otis quickly grows impatient waiting for his fatherís arrival. Leaving the women under Babyís guard, he marches Banjo and Sullivan out to their van, and orders them to drive to an abandoned chicken farm in the desert, where the Firefly family once buried a sizable cache of firearms for safekeeping. The situation for both sets of captives worsens swiftly and drastically after that.

Meanwhile, the pursuit of the Devilís Rejects (as the press is now calling the Firefly clan) is beginning to take its toll on Sheriff Wydell. What was that the philosopher said about grappling not with monsters? The tipping point for Wydell comes during his second interrogation of Mother Firefly, when she reveals an unexpected extra link between this movieís story and its predecessorís. You remember the cop whose cavalry-to-the-rescue trip to the Firefly homestead accomplished nothing but to up House of 1000 Corpsesí body count another notch? Well, it turns out he was Sheriff Wydellís older brother. Shortly after he learns that his current nemeses were responsible for the elder Wydellís murder, too, the sheriff starts getting dream visitations from his dead brother (Tom Towles once again), who proclaims that his spirit will never be able to rest until he is avenged upon the fiends who slew him. Thus begins Wydellís transformation from an officer of the law into a well-equipped vigilante on a personal revenge trip. The change first manifests itself when Wydell murders Mother Firefly in the interrogation cell after making sure that none of his fellow cops are around to witness the crime. Then he effectively sidelines his own police force, entrusting the job of hunting down the rest of the family to a pair of bounty hunters (Danny Trejo, of From Dusk Till Dawn and Anaconda, and ex-pro wrestler Diamond Dallas Page, whose other acting gigs include Driftwood and Snoop Doggís Hood of Horror) with extremely shady backgrounds. By the time Wydell finally catches up to the remaining Fireflies, itís going to be impossible to say who are the good guys and who are the bad guys anymore.

There are indeed some respects in which The Devilís Rejects represents an advance over its predecessor. To begin with, by concentrating on ripping off just one movie most of the time, it achieves a more or less normal degree of narrative focus. It might sound like Iím setting the bar awfully low by saying that, but anyone who remembers House of 1000 Corpses will understand at once what a significant step up it really is. There are still a few pointless meanderings here and there, most notably the insufferable scene that results when Sheriff Wydell calls in a movie critic in the hope of puzzling out the significance of the Firefly familyís aliases, all of which are drawn from old Marx Brothers movies. In addition to being the one comic bit in the film which simply does not work at all, that scene brings front and center the fact that there is no reason for the Marx-derived nicknames, except to serve as a movie-geek in-joke. Given all the effort that Rob Zombie otherwise invested in distancing The Devilís Rejects from the darkly screwball tone of House of 1000 Corpses, itís a much more damaging misstep than it might appear at first glance. Even so, it isnít nearly as distracting as all the black and white cheesecake clips and snippets of 30ís and 40ís monster movies that intruded themselves upon the preceding film with such frequency, and the commendable fact remains that the most annoying thing about the bit with the critic is that it puts the story on hold just as itís starting to get really interesting. House of 1000 Corpses never looked like its story was about to get interesting. The increase in seriousness is itself an improvement, tooó although it is not without its downside, which Iíll deal with in a bit. By now, my preference for straight-faced horror movies should be no secret to anyone, so I wonít belabor the point beyond to say that whatever else may go awry, I canít help but be at least a little bit impressed with a movie that can induce a twinge of genuine discomfort by showing a Bill Moseley villain getting worked over with a staple gun. Most of the time, Moseley leaves me wanting to take a staple gun to him myself.

And that, at last, brings me to the most conspicuous way in which The Devilís Rejects is better than House of 1000 Corpses, the overall level of the acting. Every time Rob Zombie has made a movie, thereís been a certain amount of grumbling over ďstunt casting,Ē with reference to his tendency to hire respected or at least fondly remembered luminaries of the 70ís exploitation scene for virtually any role that hasnít already been allocated to his wife. In the case of The Devilís Rejects, not only do we have Sid Haig, Ken Foree, and Michael Berryman, plus Bill Moseley and Danny Trejo for a more modern interpretation of the same flavor, but we also get miniscule cameos from P. J. Soles, Kane Hodder, Ginger Lynn Allen, Steve Railsback, and Mary Woronov! However, as Zombie himself will be the first to tell you, thereís an obvious reason for assembling such a cast, above and beyond the cachet of their names for a certain segment of the target audienceó most of those people are just really good at what they do. The Devilís Rejects has a drive-in dream cast, and the graver tone as compared to the previous film means that damn near everybody in it has a chance to offer up a meaningful performance. Even Sheri Moon acts with something other than her buttocks this time around (although those do indeed get their share of screen time), and while she never comes close to matching Haig or Foree, she demonstrates that thereís indeed a bit more to her than the charismatic incompetent we saw in House of 1000 Corpses. The only notable outlier from the pattern is Leslie Easterbrook, who is awful in a way that I canít remember seeing since Piper Laurieís valiant effort to singlehandedly ruin Carrie.

All the foregoing raises an uncomfortable question: if the focus is so much tighter; if the story is so much more coherent; if the tone is so much better suited to the subject matter; if the acting is so much improvedó why the hell does The Devilís Rejects leave me nearly as cold as its predecessor? Part of the problem, as Iíve said, is that it still has no ideas or personality of its own. It rips off a less obvious movie, and rips it off more intelligently and judiciously, but it has absolutely nothing new to offer. A lot of the time, Iím okay with that, but in both of the films of his that Iíve seen, Rob Zombie displays so much innate ability as a director that his utter vacuum of writerly originality becomes grating in the extreme. He has such a good eye for locations, such an instinct for wringing cockeyed beauty out of the arrestingly ugly, such a deft touch with actors whom most filmmakers resolutely wasteó and yes, such a true and intimate understanding of how and why the movies he emulates so compulsively workedó that I just want to grab him by the dreadlocks and shout, ďDamn it, Rob! Will you stop making your favorite old movies over again, and do something thatís yours already? Even if that means shooting it from a script by somebody else?Ē Similarly, I find myself frustrated by Zombieís tendency to take exactly the wrong shortcuts, which in The Devilís Rejects manifests itself most glaringly in the ostensibly 70ís period setting. As in House of 1000 Corpses, the attempt to invoke a particular era extends no further than making sure nobodyís driving a car more recent than the supposed date, and thatís nowhere near far enough. The clothes are wrong. The hair is wrong, despite the prevalence of great, bushy mountain-man beards among the male cast-members. The makeup is wrong. The interior dťcor is wrong. Sheriff Wydell and his men wearing Kevlar vests in the siege on the Firefly homestead is wrong. The nuances of peopleís styles of cursing are wrong. Banjo and Sullivanís roadie is wrong, for fuckís sakeó heís unmistakably a 21st-century retro-70ís hipster, as opposed to an authentic 70ís country-rock dirtbag. And maddeningly, the first subtly wrong detail that, once noticed, cannot be un-noticed appears not two minutes into the movie, when all weíve seen is Tiny dragging the body of his latest victim through the woods: in 1978, college-aged girls had pubic hair. If all Rob Zombie wanted was an excuse to have the Firefly family driving around in a stolen succession of cool old ragtop land-yachts, then why bother to set The Devilís Rejects specifically in 1978 at alló especially if he was going to have the hair and makeup people age Otis a good fifteen years as compared to his previous appearance, anyway?!

Really, though, Zombie put a pretty cramped ceiling on the potential of The Devilís Rejects simply by making it a sequel to House of 1000 Corpses in the first place. This is where the heightened seriousness of the second film bites it on the ass, because it asks us to treat as agents of genuine menace a group of characters that were introduced to us as Grand Guignol clowns. To see why this was doomed to failure, imagine for a moment that The Texas Chainsaw Massacre 2 had been the first entry in its series. Imagine that our introduction to the cannibal clan had come not when Sally Hardesty and her friends picked up exactly the wrong hitchhiker, but when a couple of rich pricks on a cross-country road trip got overtaken by a pickup truck driving in reverse at 100 miles an hour, and had their car carved up by a hollering goon who somehow possessed the coordination to operate both a chainsaw and a puppet made out of a mummified corpse at the same time. Imagine that the canonical Dinner with Grandpa took place not in that horrible house in the Texas countryside, but in the ruins of an implausible underground amusement park, and that instead of the vignette that every agony-horror movie for the next 35 years would want to be when it grew up, it was a Jerry Lewis routine with explicit gore. Imagine that we met the franchiseís most iconic villain not as Leatherface, but as Bubba Sawyer. And imagine that instead of the ultimate backwoods horror nightmare scenario, Tobe Hooperís debut was a misconceived black comedy about making sure nobody found out what was really in the prize-winning chili. Okay. So now imagine that the original Texas Chainsaw Massacre had been made as a sequel to that. Doesnít work, does it? And sadly, even without Dr. Satan (whose one scene was wisely cut during the final round of editing), even with the two most credulity-straining of the Firefly boys either killed off early or sidelined for the bulk of the film, it doesnít work here, either. Captain Spaulding can wash off his clown makeup after the end of the first act, but our memory of the characterís behavior in House of 1000 Corpses wonít come off with it. Bill Moseley can grow a big, unruly beard, the makeup department can switch out his stringy blonde wig for a stringy gray one, and Rob Zombie can stop writing Otis like an even cheaper copy of Paul Sawyer, but it wonít erase the knowledge that a copy of Paul Sawyer is exactly what he used to be. What The Devilís Rejects needed was a clean slate; these characters do not deserve and cannot earn the gravitas that Zombie has tried to invest them with the second time around.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact