Leatherface: The Texas Chainsaw Massacre III (1989) ***

Leatherface: The Texas Chainsaw Massacre III (1989) ***

Is there any modern film franchise that has changed hands more times over the course of 30 years than The Texas Chainsaw Massacre? When Tobe Hooper completed the original film in the series, he arranged for its release through a distributor called Bryanston Pictures, which proceeded to make a shocking shitpile of money on it, scarcely a penny of which found its way back either to Hooper or to anyone else who had been involved in the movie’s creation. Now it was hardly a novel situation for an independent filmmaker to get stiffed in this way by an unscrupulous distributor, but there was far more going on with Bryanston than was typical even in the shady business of low-budget exploitation cinema. That outfit wasn’t just a film distribution company for the drive-in and grindhouse circuits; it was also a money-laundering front for the mob, which goes some way toward explaining how Hooper and company managed to get themselves so spectacularly screwed. The law eventually caught up to Bryanston’s silent partners, and the company was dismembered and sold off in the aftermath of their conviction. When that happened, the indefatigable Menahem Golan and Yoram Globus picked up the rights to Hooper’s movie, and it was their Cannon Group that produced the first sequel. That was in 1986, by which point Cannon was already in financial trouble, and within a couple of years, the studio was up on the auction block, and The Texas Chainsaw Massacre along with it. Thus it was that by 1989, the series had yet another owner, the company whose offices would eventually become famous as the place where overworked horror franchises go to die— New Line Cinema.

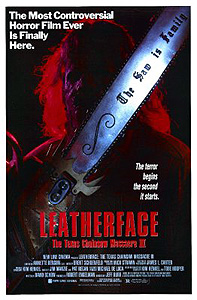

New Line’s first Chainsaw film makes, for me, another object lesson in the power of advertising, for its release marks the first time that I can recall when I was turned off of a movie I might ordinarily have gone to see by the contrary influence of an especially stupid trailer. Perhaps you remember it too. A camera pans across an idyllic and tranquil scene of a clear-watered mountain lake in the early morning, and comes to rest on the back of a burly fat man with filthy, matted hair and stained, rumpled clothes. Suddenly, out in the water, King Arthur’s Lady of the Lake stretches her dainty arm above the rippling surface, holding aloft a bronze- and chrome-plated chainsaw, the 30-inch blade of which is inscribed with black-letter calligraphy reading “The Saw Is Family.” The fat man wades out to accept this gift, and wheels about to face the camera. He is, of course, Leatherface, as played by still a third anonymous stuntman. “Fuck that,” I said, and in fact a full fifteen years would pass before I made myself give Leatherface: The Texas Chainsaw Massacre III a try. You can imagine my amazement at discovering that it’s actually a fairly decent movie, at least up until an asinine ending that hinges upon the surprise survival of no fewer than three characters whom we saw killed earlier in the story.

Screenwriter David J. Schow begins by taking the most sensible approach imaginable to The Texas Chainsaw Massacre 2: he pretends it never happened. On the other hand, he also seems to proceed upon the assumption that the first film didn’t happen quite the way we remember it, either, and that The Texas Chainsaw Massacre presents a somewhat garbled version of Sally Hardesty’s run-in with the notorious cannibal family. Leatherface’s opening crawl reveals that Sally died in a mental hospital some four years after her ordeal, and that the crimes she endured were eventually blamed on a man named W. E. Sawyer. The state’s attorney convinced a jury that Sawyer had a second personality, one which emerged only when he donned a crude, hand-made leather mask, and that this second personality— Leatherface— was responsible for the murder of Sally’s friends and brother, and very nearly responsible for the murder of Sally herself. The girl’s report of an entire family of killers was presumably dismissed as the product of her own unstable mental condition in the aftermath of the attack. Sawyer was executed in 1981, bringing the whole ugly story to as beneficent a close as was possible under the circumstances.

We, however, know better than that, and we realize what’s what when our protagonists, Ryan (William Butler, from Arena and Friday the 13th, Part VII: The New Blood) and Michelle (The Hidden II’s Kate Hodge), hear on the radio that the traffic jam on the road ahead of them is caused by a police excavation of a dry lake-bed beside the highway, where the decayed remains of some 50 people have been discovered. The couple are on their way from California to Florida, where Michelle will take a job as an airline stewardess so as to get a break from her increasingly unsatisfying romance with Ryan; one assumes the young man’s pressing obligations as a medical student have something to do with Michelle’s discontentment. The next day, still deep in the proverbial heart of Texas, they pull into a rundown service station, where the attendant (Tom Everett, of Prison and The Exterminator) exhibits a disconcerting similarity to the hitchhiker Sally Hardesty claimed to have picked up back in 1973. The attendant hassles Michelle in an inappropriately sexual manner while he fills up her gas tank and Ryan uses the service station’s men’s room, then goes inside to perv on her through a peephole in the wall when she takes her turn on the toilet. The little scumbag is restrained from doing worse only by the presence at the station of a hitchhiking man in cowboy garb who calls himself Tex (Viggo Mortensen, later of Peter Jackson’s The Lord of the Rings trilogy and Gus Van Sant’s Psycho remake), and whose interest in Michelle is more tactfully expressed if no more pleasing to her soon-to-be ex-boyfriend. Except that even Tex is unable to keep the attendant in check after he is caught spying on Michelle; the man emerges from the office a moment later with a shotgun and apparently blows Tex away as the two travelers speed off down the road!

Alfredo (for that is the attendant’s name) isn’t alone at the gas station, either. Just after sunset, he dispatches somebody else to go after Ryan and Michelle in a gigantic, Road Warrior-ish pickup truck. The truck’s driver catches up to his quarry later that night and runs them off the road, but that’s only the beginning of their troubles. While Ryan scrambles to change the tire the car lost while skidding onto the shoulder, a huge, masked man (R. A. Mihailoff, who can also be seen in small, thuggish roles in Trancers 3: Deth Lives and Stripteaser) armed with a chainsaw creeps up on them, and nearly kills them both. And though Ryan and Michelle escape this second assault as well, their flight is cut short when, in their panic, they narrowly avoid colliding with the only other vehicle on the road, the Jeep being driven by a wilderness-survival hobbyist named Benny (Ken Foree, from Dawn of the Dead and Sleepstalker: The Sandman’s Last Rites). Both drivers lose control and roll their machines over, Michelle’s car tumbling down the steep, wooded embankment on her side of the road.

Benny doesn’t initially believe Ryan when he says that he and Michelle were running away from a pair of armed lunatics. But then Michelle regains consciousness and repeats the seemingly incredible story, which gets the survivalist thinking there may be danger afoot after all. Shortly thereafter, Benny encounters that danger firsthand, for the hook-handed hillbilly (Joe Unger, of A Nightmare on Elm Street and Pumpkinhead II: Blood Wings) who drives up and offers to help him flip his Jeep back onto its wheels is none other than the driver of the truck that trailed Michelle and Ryan from the gas station. Benny has just enough time to retrieve his AR-18 from the back of the Jeep and retreat into the woods before Captain Hook makes to run him over. This, of course, means that Benny is headed straight for Leatherface, and the ensuing confrontation goes very badly for the weekend warrior until the killer is distracted by a teenage girl (A Nightmare on Elm Street 5: The Dream Child’s Beth DePatie) who looks like she could teach Benny a thing or two about living off the land under highly adverse conditions. “Hey, scumbag! It’s me you want, remember?” the girl calls, and she must know what she’s talking about, because Leatherface does indeed go off in pursuit of her.

That’s three psychos we’ve got running around the countryside— you want to try for four? Once they have their wits sufficiently collected to leave the site of their crippled Mercedes, Ryan and Michelle meet up with Tex, who evidently survived the altercation with Alfredo after all. And why not— the two men are brothers, you know! Ryan gets caught and clubbed over the head, but Michelle breaks away, and runs until she reaches a substantial country house. Unfortunately for her, this happens to be where Tex, Alfredo, Leatherface, and Captain Hook live, together with their wheelchair-bound, tracheotomied mother (Miriam Byrd-Netherly, of The Offspring and Stepfather II), their unexpectedly dangerous kid sister (Barb Wire’s Jennifer Banko, who also played the young Tina in Friday the 13th, Part VII), and the mummified corpse of their grandfather, to which they “feed” the blood of their victims. Michelle finds herself trussed up and nailed down to a chair in the dining room in short order, while the lunatics prepare to butcher Ryan before her eyes. The thing is, Leatherface didn’t catch up to the girl in the woods (subsequently revealed to be the sole survivor of the killer clan’s last crop of victims) for at least a couple of hours, and he lost track of Benny completely while he was chasing after her. Not only that, Benny and the girl had a chance to link up briefly in the interim, with the result that Benny now knows that there is a whole brood of loonies in the neighborhood, operating out of a house not far away. Chainsaws and sledgehammers might make formidable weapons at close quarters, but given the choice between them and an AR-18, my money’s on the assault rifle.

David J. Schow was a good choice for the writer of a Texas Chainsaw Massacre sequel. He first achieved notoriety as one of the “Splatterpunks” (in fact, the term is of his coinage), the horror authors of the 1980’s whose stories proudly displayed the influence of the preceding decade’s increasingly aggressive cinematic shocks and scares, so there’s something most fitting about Schow being tapped to continue the story of a film that had such impact on his own writing. Some of the decisions he made regarding how to handle the task are a bit puzzling (like giving Leatherface an entirely new family, for example), but overall, I’d say he did a creditable job. At the very least, he brought the franchise back to its roots after the irksome and contemptible foray into self-parody that was The Texas Chainsaw Massacre 2, which is more than you can say for the screenwriters of most late-80’s slasher sequels. Beyond that, however, Schow seems to realize that a great deal of the first film’s strength derived from its memorable— but not excessively flamboyant— characters. There is a fine line between the stylized eccentricity of Hooper’s original cast and the campy caricatures of the first sequel, and locating that line is a tricky business. Schow finds the line here, and even manages to squeeze right up against it without crossing over in a couple of scenes. I also found it very interesting that Schow has written the new family in such a way that it becomes possible to see them as the “real” people on whom the various cannibal killers in the previous movies were “based.” If we accept (as I think was Schow’s intention) this movie’s predecessors as a sort of urban legend that sprang up around the activities of the family as presented here, then certain natural parallels between these family members and the others come to light: the legend turns Alfredo into the hitchhiker, Captain Hook and Tex blend to become Paul/Choptop, the mother takes on other elements of Hook’s personality and then divides to become Drayton Sawyer and the embalmed grandmother, and Grandpa’s preserved corpse changes in the retelling to become a living but unfathomably ancient man kept just to this side of the grave with the blood of the clan’s victims. It makes the movie cleverly self-referential without being cute and annoying at the same time.

Director Jeff Burr, meanwhile, accomplishes something I would not have believed possible had I not seen it with my own eyes. He renders much of the first half of this movie genuinely suspenseful. Leatherface: The Texas Chainsaw Massacre III never comes anywhere near the hellish psychological brutality of the original, and it suffers a bit from the glossy look of the production (which might have something to do with its having been shot in California, rather than Texas), but Burr makes good use of some simple but effective tricks that your average slasher director is too incompetent to wield or too lazy to bother with. The scene in which Leatherface stalks Ryan and Michelle after their car loses its tire is especially well done. Whereas most slasher movies would play this scene according to the usual “unsuspecting prey vs. POV cam” formula, Burr makes it clear that Leatherface’s intended victims know someone is hunting them, and eschews the POV in favor of a giallo-like use of suggestive close-ups on an unrevealing part of the killer’s body (in this case, his steel-braced right leg) to indicate his presence. When working within a formula as rigid as the slasher movie, it is important to find as many small new ways to do things as possible— otherwise, your movie will have no means of establishing its own personality. Burr seems to have understood that, and even if his style marks him as more of a craftsman than an artist, that still puts him at a higher level than the directors of most 80’s horror sequels managed to reach.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact