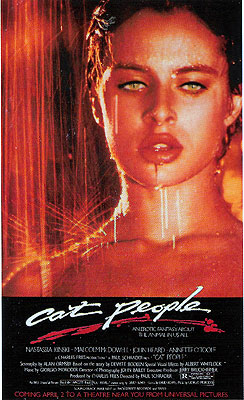

Cat People (1982) ***

Cat People (1982) ***

Paul Schrader’s Cat People is a striking example of how personal a work-for-hire assignment can become, given the right circumstances. The project was not in any sense Schrader’s idea; indeed, it had been wandering in Development Hell for eighteen years by the time he came aboard. Remaking Cat People had been on the “to do” list of Amicus Productions founders Milton Subotsky and Max Rosenberg since 1963— which would have made their version the fledgling studio’s third film, and its first horror picture, had Subotsky and Rosenberg jumped on the idea right when they had it. Something else always came up, though, and it wasn’t until 1975 that Amicus went so far as to purchase the remake rights. Had they produced it then, Cat People would have been the final Amicus horror film, for 1975 was when the company began its pivot into Lost World fantasy instead. Of course, it turned out then that the firm’s days were numbered anyway, so that the end of 1977 found Cat People not merely an unmade movie, but an unmade movie without even a studio to make it. The next three years or so saw an astonishing rogues’ gallery of writers and directors come and go, as one production company after another toyed with the ball that had slipped from Amicus’s dead hands: Bob “Black Christmas” Clark, Roger “Blood and Roses” Vadim, Howard “Saturday the 14th” Cohen, Alan “Children Shouldn’t Play with Dead Things” Ormsby— to say nothing of Brian De Palma, John Carpenter, and David Cronenberg, each of whom was under consideration to direct at some point after Vadim’s departure in 1979, although none of them were ever formally attached.

Schrader was finally offered the job once Cat People evolved into a co-production between Universal and a briefly resurgent RKO Pictures, at the suggestion of a talent agent named Michael Black. Producer Marianne Maloney had evidently approached Black for some outside-the-box nominations, and the director of Hardcore and American Gigolo certainly fit that bill. Schrader’s reasons for accepting the gig were as counterintuitive as his involvement in the first place. He took it on precisely because he didn’t initially give a shit about a new Cat People one way or another. Feeling thoroughly wrung out after a string of intense, high-profile, “auteur”-type films, Schrader couldn’t seem to make any of his own ideas come together into anything usefully coherent. A quickie programmer in a genre he didn’t respect therefore seemed not unreasonably like a good way to recharge his creative batteries while still keeping busy. But as it happened, an explosive on-set romance with lead actress Nastassja Kinski turned Cat People, for Schrader, into the kind of obsessive, psychically wounding experience that leaves a man with no other option but to torch his whole day-to-day existence, move to Tokyo, and make a biopic about Yukio Mishima. (Rich, successful Hollywood guys have very different nervous breakdowns from you or me…) You don’t have to know the story, either, to sense that some manner of torment was involved in Cat People’s creation. The whole film has an unmistakable scent of rotten hormones and bad craziness, which is just about the strongest single asset that a sex-horror flick can possess.

Ages and ages ago, in what I take to be one of the less fertile parts of the Fertile Crescent, there lived a tribe whose warrior caste venerated the local leopard population. It was only fitting that they should, too, because those were no ordinary cats. Not only were they all melanistic, and therefore especially striking to behold, but they were also both unusually social and unusually intelligent. It had been the warriors’ practice since time immemorial to combat famine and drought by delivering maidens from their tribe to the leopards in sacrifice, but at some point the cats stopped eating the girls, and started mating with them instead. The result was a lineage of were-panthers whose transformations were brought on by sexual arousal, and who would then remain in feline form until they had taken human life. If the object of a were-panther’s lust was one of its own kind, however, then the creature could indulge without releasing the beast within. The trouble, from the were-cats’ own perspective, is that even after thousands of years, their worldwide population remains vanishingly small— small enough, in fact, that only a few of them ever get to enjoy the luxury of each other’s company.

You won’t have to spend much time with Paul Gallier (Malcolm McDowell, of Get Crazy and Time After Time) to suspect him of being one of those cat people. Nor will you have any difficulty figuring out what’s really on Paul’s mind when he gets in touch with his long-separated kid sister, Irena (Kinski, from Blind Terror and To the Devil… a Daughter!), on the occasion of her coming of age, and invites her to his home in New Orleans. None of the affections he showers on the virginal young girl after picking her up at the airport look the slightest bit brotherly. One simply doesn’t leap straight from “hello” to lycanthropy and sibling incest, however, so Paul is careful to leave some room for plausible deniability in his interactions with Irena that first night while they catch up on what they’ve been doing with their lives since their parents’ double suicide landed them in separate orphanages a decade and more ago.

Gallier is considerably less careful, though, regarding how he scratches his itches in the meantime. As soon as Irena goes to bed that first night, he books himself an appointment with a masseuse (Lynn Lowry, from Dead Things and Score), knowing full well what’s almost certain to happen as a consequence. That “almost” goes in an unexpected direction, however. Yes, Paul gets so horny just thinking about the masseuse that he’s already changed by the time she arrives at the skeezy hotel where she prefers to meet her clients. And yes, Paul attacks her from under the bed before she’s even finished taking off her clothes. But the girl is a lot faster than she looks, even with a mauled foot, and cats can’t operate doorknobs. Gallier ends up locked in that flophouse room until morning, by which point the hotel manager has called the police, and the police have called the Audubon Zoo. Zoo administrator Bill Searle (Scott Paulin, from Tales of an Ancient Empire and Forbidden World) arrives in person, followed in short order by curator Oliver Yates (John Heard, of Too Scared to Scream and C.H.U.D.) and two experienced keepers by the names of Alice Perrin (Annette O’Toole) and Joe Creigh (Ed Begley Jr., from Streets of Fire and Sensation). They set about capturing what they assume to be some rich asshole’s escaped exotic pet, and the next thing Paul knows, he’s locked up in a cramped brick-and-wrought-iron cage in the zoo’s 80-year-old big-cat house.

Meanwhile, Irena is understandably freaked out about her brother’s vanishing act not a dozen hours after taking her in at his place. Paul’s housekeeper, Female (Ruby Dee)— it’s pronounced so as to rhyme with “tamale,” which is a tale in itself— says that he had urgent business at the Pentecostal church where he works in some lay capacity or other, and advises Irena to spend the day exploring the city on her own. But when her brother still hasn’t returned come sundown, and no one at the church can shed any light on his possible whereabouts, Irena begins to worry. Eventually, she’s driven to the desperate measure of hiring a taxi to carry her aimlessly around New Orleans in the hope that she might randomly spot her missing brother.

Irena won’t understand this for a while, but that actually ends up being the winning ticket. When her cab passes by the entrance to the Audubon Zoo, the girl gets a funny feeling. She finds herself inexplicably drawn not just to the zoo, but to the cat house specifically. And then she feels even more inexplicably compelled to spend the rest of the day obsessively sketching the newly acquired black leopard which she naturally doesn’t recognize— at least, not consciously— as the very man she’s been searching for. Indeed, she keeps it up until after closing time, which is how she makes the acquaintance of Oliver Yates. The pair become friends within barely an hour of their meeting, and begin feeling the first inklings of romantic interest in each other only a little less hastily. That’ll become a point of friction with Alice, who has long harbored a crush on Oliver, but we’ll go into that later. The main thing for now is that Yates uses the power of his position as curator to engineer an infinity of excuses for him and Irena to bump into each other in the future by offering her a job at the Audubon Zoo gift shop. Between work and budding romance, Irena’s worries about Paul fade a bit toward the back of her mind over the ensuing days. She’ll be seeing her brother back in human form soon enough, however, because Joe Creigh, for all his experience with large, dangerous animals, has never dealt with one that specifically desired his death. Joe gets too close while attempting to hose out Paul’s cage, and the human cat lunges out between the bars to seize his arm and tear it from the socket. Irena is on hand to witness the horrid scene, but she, Oliver, and Alice are all too busy trying to help their mortally wounded friend to observe what happens next. By the time they’ve got any attention to spare for a homicidal leopard, Paul has regained his outward humanity and escaped.

Now Gallier may have been a leopard on all the occasions when he saw Irena and Oliver together at the zoo, but even in animal form, he knows what he knows about human courtship behavior. He understood at once what was up between his sister and the curator, so as soon as he comes home (“Where were you?!?!” “In prison… praying with the condemned.”), he undertakes to have The Talk with Irena. You know The Talk— the one about how he and his sister are were-cats, and how their parents were both were-cats and siblings as well? About how brother-sister incest is the only really dependable way for “people” like them to get laid without turning into man-eating panthers? About how he and Irena should totally hook up before she starts slaughtering her lovers, and so that he can stop slaughtering his? Yeah, well, all The Talk accomplishes is to convince Irena that her brother is a fucking lunatic, leading her to flee the house. She happens to make her escape just as a police car is cruising by, which naturally leads in turn to the cop becoming curious about the screaming girl running down the street. And more importantly, the K-9 German shepherd in the prowl car’s back seat becomes curious about something he smells coming from the Gallier place. Paul himself manages to slip out before the heat really comes down, but by the end of the night, the house is crawling with cops, and the secret bestiality dungeon in the basement isn’t a secret anymore. Naturally Detective Brandt (Frankie Faison, from Maximum Overdrive and Hannibal) doesn’t grasp what’s really been happening, but his theory that Gallier is the mysterious owner of the killer leopard that attacked the masseuse and escaped from the zoo isn’t too far off. Nor is his corollary theory that Paul has been feeding hookers and runaways to the big cat for untold years now. Female is arrested as Paul’s accomplice, and Irena moves in with Oliver, reasonably having no desire to live in an active crime scene.

Alice isn’t thrilled with the latter turn of events, of course. She warns Yates— and not for the last time, either— that he’s getting in over his head with this girl, but Perrin’s obvious ulterior motive would tend to undermine her credibility on the subject, even if she weren’t absolutely right, and Oliver could still think straight about Irena. But even Alice doesn’t understand how far over his head Yates is getting. Although Irena consciously dismisses everything Paul told her as the raving of a madman, she can’t help recognizing subconsciously that there’s some kind of truth in it. Despite her growing feelings for Oliver, and despite now living under the same roof with him, she finds herself afraid to consummate their relationship— which rather throws a spanner into the works, from Oliver’s point of view. Still, Yates figures this sudden sex phobia is understandable given the circumstances, and will sort itself out in time with enough patience and gentleness on his part.

Oliver starts by taking Irena out of the city to the most stress-free place he knows, the cabin on the bayou that he built with the help of his old friend, Yeatman Brewer (Moon of the Wolf’s Emery Hollier). At first there’s every indication that the change of scenery is doing her good, but then one night she gets out of bed in the wee hours of the morning, slips off her nightgown, and sneaks out of the house to hunt down a rabbit and kill it with her bare hands and teeth. That may not constitute proof that she’s a were-panther, but it does cause Irena to worry that she’s starting to go the exact same kind of crazy as her brother. Meanwhile, back in town, Paul is keeping Brandt busy cleaning up the aftermath of his consolation fucks, staying comfortably ahead of the law thanks to the detective’s crucial misapprehension that leopard and man are two separate entities. Oliver and Alice try to help out with the former aspect of the hunt, but they of course face the same handicap as the police. Yates learns what’s really going on only after Irena, overcome by escalating fear of incipient madness, runs away from him and returns to Paul’s home in order to gather up her stuff for an escape from New Orleans. Naturally that’s the first place Paul will look for her, and Oliver isn’t far behind. The ensuing clash between the men in Irena’s life provokes Paul to deliberately induce transformation, and although Oliver narrowly emerges both alive and victorious, his were-cat problems are actually just beginning.

This Cat People ultimately resembles the other one a bit more than you’d gather from the foregoing synopsis, but only because it suddenly gets serious about being a remake in the fourth act. The transformation is as complete and as startling as the one Irena undergoes to kick off the climax, and challenges audience engagement in a way not dissimilar to how Oliver’s affection for his girlfriend is challenged by having her turn into a leopard on top of him. To be sure, the Schrader-Orsmby Cat People is an effective enough rethinking of the Tourneur-Lewton version once it finally decides to be that. But it was a better standalone sex-panther flick, and its two personalities don’t really have much to do with each other. It’s principally a matter of conflicting love triangles. In the original, Oliver was torn between his deep-rooted but low-intensity affection for the wholesomely tomboyish Alice and his consuming but superficial passion for the exotic and mysterious Irena. The result was somewhat like a distant forerunner of Fatal Attraction, if the Michael Douglas character had married Glenn Close and then cheated on her with Anne Archer. For that dynamic to function, Irena needs to be at least a tad villainous from the outset, and indeed Simone Simon played her as someone of whom Sam Spade or Philip Marlowe might ruefully remark, “I knew the dame was trouble from the moment she stepped into my office.” In this Cat People, however, it’s Irena who has the competing benevolent and malign suitors, making her more a traditional gothic heroine than a noirish femme fatale. When the fourth-act shift from Paul-Irena-Oliver to Irena-Oliver-Alice occurs, it makes no sense that the embattled virgin of the preceding 90 minutes is now herself the embodiment of sexual peril. The filmmakers attempt to paper over the gap with a fantastical dream sequence in which Irena discovers and accepts the truth about her origin, but the change in her story role remains psychologically incoherent. Fortunately Schrader and company right the ship at the last moment with the weirdest happy ending I’ve seen in years— one which gives Oliver, Irena, and Alice alike some approximation of what they want, while simultaneously acknowledging that no conventional means of doing that is at all viable under the terms already established.

Despite what I just said about Cat People’s first three acts having little to do with the business of remaking the earlier film, the story that Ormsby and Schrader are telling throughout that hour and a half is rooted in the source material in an interesting way. For all the Lewton-Tourneur Cat People’s self-conscious modernity and emphasis on the psychological dimension, Irena herself has a pronounced fairy tale quality, both as a character and as a monster. This version runs with that by making explicit the prehistoric antiquity of the magic in the Gallier bloodline. Both the Bronze Age prologue and the dream sequence in which Irena meets her more purely feline ancestors display a perfectly calibrated unreality, plainly marking the setting as Once Upon a Time in contrast to the naturalistic New Orleans of the film as a whole. That heightened tension between the fantastic and the mundane gives Cat People a second thematic power source to compensate for its deficiencies of character logic, making this movie a fit companion piece to that other “lycanthropy, Freud, and fairy tales” picture from the first half of the 80’s, The Company of Wolves.

Cat People resembles The Company of Wolves, too, in linking lycanthropy so overtly to psychosexual concerns. Indeed, it hits the erotic aspect so hard that it almost feels like something out of 1970’s Europe. And frankly, given this movie’s leading lady, wouldn’t you kind of feel cheated if that weren’t the case? Nastassja Kinski wears Irena’s virginity like a corset, confining and restricting her sex appeal while simultaneously calling exaggerated attention to it. And then once her dreams enable her to embrace her animal self, the result is a veritable explosion of lubricity. There’s no gainsaying the sheer erotic heat that Kinski brings to each of Irena’s two faces, however little sense the transition between them makes. It’s no wonder Schrader fell so hard for her! Malcolm McDowell is similarly effective as the venereal devil hovering over Irena’s left shoulder, a role which is all the more powerful and intriguing because Paul, when you really think about it, is basically right about a lot of things. It’s only natural to read Gallier as a figure of temptation into evil, because what else should we make of a pitchman for sibling incest with a long history of hooker-eating? But his main motivation for pursuing the former is so that he can stop doing the latter, while at the same time preventing his beloved sister from going down the road he’s already traveled. And the uncomfortable fact is that Irena is what her brother says she is, so that her long-delayed coupling with Oliver yields results that differ from Paul’s warning only insofar as love grants Irena sufficient self-control, even in animal form, to kill somebody else in Oliver’s stead in order to regain her guise of humanity. If only she’d listened to the gross, creepy weirdo obsessed with sister-fucking, a whole lot of bloodshed could have been averted!

The last thing I want to call your attention to about Cat People is the unusual amount of thought that its creators put into the specifics of lycanthropy. Most were-critter movies offer a disappointingly generic interpretation of what it means to have an animal alter-ego, even when they take the trouble to have the beast-self inform the characterization of the human side. In Cat People, though, the Gallier siblings are unmistakably and consistently portrayed as cat people. For one thing, the enhanced abilities which they gain courtesy of their condition are very particularly feline, involving jumping, climbing, and landing on their feet after falling from great heights. The filmmakers also made things both easier for themselves and more thematically resonant by eschewing the beast-man model of lycanthropy that’s been dominant in the movies since Werewolf of London in 1935. Although both Paul and Irena are shown at various times in intermediate stages of transformation, the endpoint is always outwardly indistinguishable from an ordinary panther. That’s in keeping with how shapeshifting is generally portrayed in myth and folklore, which ties back into the fairy-tale mood that I was talking about before. Furthermore, Schrader ended up making extremely sparing use of the animatronic puppets that he commissioned from Ellis Burman’s Cosmokinetics SFX shop, preferring to have the werecats played by live animals to the maximum extent possible. The puppets came into play only when a scene called for something too dangerous or difficult to attempt with a genuine cat, sparing the puppeteers the need to study and master feline mannerisms. (Note, however, that most of the four-footed performers were pumas, rather than the leopards specified in the script. Leopards prefer to spend the hours of daylight sleeping in a treetop somewhere, and they become cross when some soft, weak, and manifestly edible biped tries to tell them different. Pumas, in comparison, are easygoing, even-tempered beasts, altogether more cooperative, predictable, and trustworthy.) The studying was left to Kinski and McDowell, the latter of whom especially takes his catlike behavioral tics to unnerving, uncanny extremes. When Paul first introduces himself to Irena at the airport, he doesn’t so much embrace her as rub his cheek against hers as if trying to mark her with his scent, and there’s a bit following one of his returns to human form that I can’t concisely describe, but which anyone who’s ever lived with cats of any species will recognize instantly. Reportedly most of Paul’s ailurisms were improvised on the spot, leading me to suspect that McDowell is the other kind of cat person in real life.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact