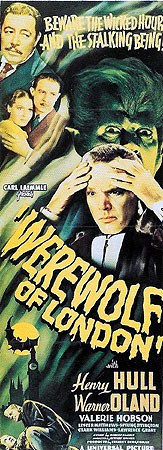

Werewolf of London/Unholy Hour (1935) **½

Werewolf of London/Unholy Hour (1935) **½

Werewolf of London was certainly Universal Studios’ first werewolf film. It appears also to have been the first talkie to deal with the subject, and indeed, it may even have been the first feature-length werewolf flick, sound or silent. I know of at least one previous film in the subgenre, 1913’s The Werewolf, but it was merely an 18-minute short. Nevertheless, despite its pride of place, this movie has sunk into comparative obscurity, overshadowed by the later The Wolf Man and its monster rally sequels, Frankenstein Meets the Wolf Man, House of Frankenstein, and House of Dracula. (Yeah, I suppose I ought to count Abbot and Costello Meet Frankenstein in there, too…) To some extent this is understandable. The Wolf Man is undeniably the superior film, its main character and the actor who portrays him are far more charismatic than their counterparts here, and its arcane, supernaturalist werewolf lore took a much firmer hold on the popular imagination than the more prosaic version presented by its older cousin. But the oft-repeated complaints about this movie’s star and the unpleasant character he plays are completely beside the point, and in retrospect, it is the very failure of Werewolf of London’s variation on the lycanthrope legend to catch on that makes the film seem like such a refreshing change of pace.

The setup is familiar enough-- the old standby of the “civilized” traveler poking his nose into remote, superstition-soaked corners of the world and unleashing thereby some ancient evil to which the modern world is made vulnerable by its refusal to believe in it. In this case, the interloping Westerner is a botanist named Wilfred Glendon (Henry Hull, who would go on to appear in Master of the World, along with great numbers of more respectable movies), and the remote corner of the world is an inaccessible valley in the mountains of Tibet (stood in for by a decidedly un-Tibetan-looking rock formation about an hour’s drive from downtown L.A.). What brings Glendon to Tibet is an extremely rare species of flower called Maripasia lumina lupina, which blooms only by the light of the full moon. So rare, in fact, is this plant that only a single individual is known to exist, and it lives in the valley to which Glendon has made the long trek from London. The problem with this, as you might have guessed, is that the valley in question is said to be positively infested with demons and evil spirits, and none of Glendon’s bearers or guides will set foot in it. And as you might also have guessed, the “superstitious” bearers have the right idea. When Glendon forges ahead without them, he is attacked by some sort of beast-man mere moments after he spots the Maripasia. He beats the creature senseless with his walking stick, driving it off into the hills, but it gives him a couple of wicked injuries to his right forearm to remember it by. The triumphant Glendon then does what any botanist would have done with an unbelievably rare and notoriously delicate plant in 1935-- he uproots it and carts it back to his private laboratory in London.

Further underscoring the arrogance of Western science, Glendon’s reason for committing this gross affront against nature is about the stupidest one that can be imagined. He has developed a special electric lamp designed to mimic exactly the frequency characteristics of natural moonlight, and he wants to test his invention. Surely there has to be a better way to do this, one that doesn’t involve slogging through the mountains of Tibet and risking both your life and the death of the only known member of an endangered plant species by hauling it fully a third of the way across the globe from its natural habitat! I mean, the world is full of night-blooming flowers, many of them native to the British Isles! And perhaps Glendon has some idea how stupid and irresponsible his project is, because he is conducting it under the strictest secrecy, concealing his work even from his wife, Lisa (Bride of Frankenstein’s Valerie Hobson). So if the Maripasia project is so hush-hush, why, then, do you suppose Glendon is throwing a party at his house, to which he has invited every botanist, botanist wannabe, and botanist groupie in England? I can’t answer that one either.

There are two guests at this party who will come to have a big impact on Glendon’s life. One of them is Captain Paul Ames (Lester Matthews, from The Raven and The Son of Dr. Jekyll), an ex-boyfriend of Lisa’s who clearly still has the hots for her, and whose hots are less than fully unrequited. The other is a Japanese botanist named Yogami, who claims to have met Glendon in Tibet, though Glendon remembers no such encounter. (I’d like to pause here to say a few words about Warner Oland, who plays Dr. Yogami. Connoisseurs of vintage racism take note... Oland was a Swede who built an entire career playing Asians, to which his uncharacteristically dark hair and puffy, drooping eyelids [the mark of Saami ancestry, perhaps?] made him bear the tiniest imaginable resemblance. Oland played the title characters in most of the Charlie Chan and Fu Manchu movies of the 30’s and 40’s. What-- surely you didn’t expect the Hollywood suits to cast a [gasp!] Chinaman in roles like that, did you? Not in a speaking part?!?!) Anyway, Yogami says he and Glendon were in Tibet on “similar missions,” and he’d very much like to know if Glendon was successful in his. Yogami is interested in the outcome of Glendon’s “mission” because the flowers of the Maripasia lumina lupina are supposed to be able to give temporary relief to sufferers of lycanthropy (which Yogami hilariously calls “lycanthrophobia” throughout the film). Glendon may scoff, but Yogami swears he knows of two cases of lycanthropy in London itself at that very moment! Glendon doesn’t quite seem to get the hint, but hopefully you do.

He gets it a few days later, though, when the light of his moon-lamp turns one of his hands all clawed and hairy while he messes around with the Maripasia plant. Remembering what Yogami told him earlier, Glendon breaks off one of the plant’s blossoms and sticks himself in the hand with its woody stem, allowing the sap to seep into his bloodstream. Sure enough, Glendon’s hand turns back to normal. The thing is, the plant has no more blooms on it-- just a couple of buds that steadfastly refuse to open-- and the moon is set to become full the very next night. Then somebody (just guess who) breaks into Glendon’s lab and steals the finally-opening buds from the plant, leaving Glendon up the proverbial Shit Creek without the proverbial paddle.

Glendon’s first transformation into his lupine alter-ego is one of the high points of the movie. Rather than have the camera close in on his immobile face while the makeup crew glues fur and fangs and pointed ears onto him between frames (an approach we’ll see a lot of in the wolf man flicks made in the years between Werewolf of London and An American Werewolf in London), this film adopts the startlingly clever tactic of having the camera follow Glendon as he passes a row of stout pillars holding up the facade of some building or other. Each time Glendon emerges from behind one of those pillars, he has a little more werewolf makeup on than he did a moment before. It’s a simple trick, but a very effective one. Glendon heads for his aunt Ettie’s house (Ettie [Spring Byington] is the most frequently seen member of Werewolf of London’s agonizing comic relief triumvirate), where Lisa and Captain Ames are attending a party without him. He doesn’t find either of the probable would-be adulterers, and he is forced to break off his attack on Aunt Ettie when her screams of terror bring every man in the house rushing to the drunken hostess’s room, so Glendon contents himself by carving up the first woman he comes across on the street as he flees.

We’ve still got three nights’ worth of full moon, though, so Lisa and Ames are far from safe. Glendon, to his credit, takes steps to protect them from himself, but it’s harder to keep a vengeful werewolf down than he realizes. First he pretends he must go away on a business trip for a couple of days, and arranges to rent an upstairs room from a pair of gin-swilling old widows (the rest of the comic relief-- the funniest thing about them is the fact that one is named Mrs. Whack). But werewolves turn out to be good climbers, and eight hours and a few victims later, Glendon goes back to the drawing board. This time, he gets himself locked up in a well-nigh impenetrable outbuilding on the estate of Lisa’s family (whose ranks have been thinned by time to include only her ancient mother and the household servants), but that plan fails when Lisa and Ames decide to go there too for a walk in the garden. When the enraged werewolf sees the couple together just outside his hiding place, he simply rips out the iron bars on the outbuilding’s window and goes after them. Ames, who had been working with Scotland Yard detective Sir Thomas Forsythe (Lawrence Grant, of The Ghost of Frankenstein) on the mystery of the wolf man killings, recognizes the attacking werewolf as Glendon. The next night, when the werewolf makes another attempt on their lives back at Glendon’s house after killing Yogami (Glendon caught him stealing the last Maripasia blossom), Forsythe is there waiting with a small army of policemen, who shoot the monster down just before he gets his hands on Lisa. What follows must surely be the only deathbed oratory by a werewolf in the history of cinema.

Despite its sometimes dragging pace, often ridiculous script, unnecessary and unfunny comic relief, and implausibly portrayed supporting characters, Werewolf of London is among the more entertaining 1930’s horror films I’ve seen. Its detractors tend to cite two shortcomings in disparaging the movie, the excessive similarity it supposedly bears to the 1931 version of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde and Henry Hull’s thoroughly unsympathetic portrayal of Dr. Glendon. I can’t for the life of me understand the first complaint, as just about the only commonality I can find between Werewolf of London and that version of the Jekyll and Hyde story is the fact that the central character in both films is a scientist who periodically turns into a savage subhuman. I also think the second is equally misguided, the result of those who espouse it inappropriately comparing Glendon to Lon Chaney Jr.’s Larry Talbot in The Wolf Man. Hull’s Glendon ought to be looked at instead as the precursor to Michael Gough’s mad genius characters of the 50’s and 60’s, who were invariably smug, swaggering pricks with superiority complexes and chips on their shoulders the size of Orson Welles. Hull’s is one of the better renditions of this sort of character I’ve seen, perhaps because his famously sincere contempt for the character of Glendon, and indeed for the movie as a whole, led him to push the envelope of obnoxiousness. If you don’t insist on seeing Glendon as something he’s not, there’s nothing wrong with Hull’s performance whatsoever. A werewolf movie whose screenwriter couldn’t pronounce “lycanthropy” has enough problems of its own; I think everybody should do Werewolf of London a favor, and stop asking it to be The Wolf Man. You might like it a little better then.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact