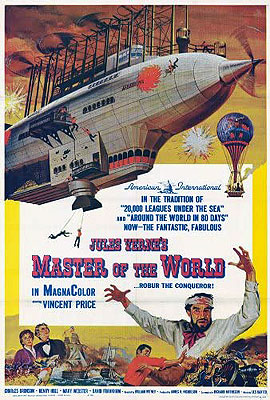

Master of the World (1961) **

Master of the World (1961) **

Having already written reviews of movies based, however loosely, on the works of Poe (Tales of Terror, War-Gods of the Deep), Lovecraft (Die, Monster, Die!), H.G. Wells (War of the Worlds), and Edgar Rice Burroughs (The Land that Time Forgot), I suppose itís about time I turned my attention to that other perennial favorite of mid-century fantasy filmmakers, Jules Verne. Master of the World is built from pieces of two of Verneís novels-- Master of the World (duh) and Robur the Conqueror-- but for the most part, it just comes across as 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea in a zeppelin. (Okay, so itís not really a zeppelin. As its owner points out with great pride, the Albatross is a heavier-than-air craft, and thus has more in common-- all appearances aside-- with the Enola Gay than with the Hindenburg. But if I called it, say, 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea in Count DiCapitoís air fortress, only four people in the entire world would have any idea what I was talking about.)

Unfortunately, before we get to any of the action, we must first endure an ill-conceived prologue describing manís eons-long quest to conquer the skies. This segment consists of a voice-over narrating famous stock footage of failed flying machines, some of it probably real, but most almost certainly taken from otherwise forgotten silent comedies of the teens and twenties. This goes on for what seems like a good 45 minutes, though it canít possibly be more than ten. Then, just about the time that I was starting to think I could stand no more, the narrator finally got around to the Wright Brothersí flight at Kitty Hawk, signaling that the film could at last begin in earnest.

And an earnest beginning it is, as life in a small Pennsylvania town is brought to a momentary standstill by a series of explosions on the peak of the matte painting of a mountain that overlooks it. The mysterious explosions are followed by the voice of Vincent Price booming down, titanically amplified, from said peak with one of the more anti-militaristic verses of the Bible. Now, thereís simply no way that something like this can happen without attracting somebodyís attention, and the somebody in question happens to be an agent of the federal government by the name of John Strock (Charles Bronson. Really.). Strock seeks out a coven of aviation enthusiasts from Philadelphia in the hope of securing their aid in getting to the top of the unscalable matte painting, and after suggesting a solution to a technical problem that has Prudent the club president (Henry Hull, from Werewolf of London and One Exciting Night) and his future son-in-law Philip Evans (David Frankham, whom you may remember as Philippe DeLambreís backstabbing colleague in Return of the Fly) all but coming to blows, he is able to win the cooperation of both men. But weíre going to need a woman in this movie, you realize, and screenwriter Richard Matheson provides one for us in the form of Prudentís daughter (and Evansís fiancee) Dorothy (Mary Webster).

With the protagonists thus assembled, itís time at last to get down to business. The team flies to the painted mountain (an aside: the characters repeatedly refer to a crater at its peak, and yet all are adamant that a conventional geological explanation for the disturbance in the first scene is impossible because there are no volcanoes in the area) in the fliersí clubís new propeller-driven hot air balloon, only to be shot down by rockets fired from the peak. However, because the movie is at most half an hour old, there can be no question but that all four aviators have survived. The great irony of the situation is that they must thank for this the same man who shot them down in the first place: the mysterious Robur (do you really need me to tell you that this is Vincent Priceís part?).

Strock, Evans, and the Prudents regain consciousness to find themselves locked in what is to all appearances a shipís stateroom. This is odd to say the least, because precious few ships ply Pennsylvaniaís portion of the Appalachian Mountains, but it is made even more so by the fact that everything in the cabin-- door and walls included-- is made of a material that none of them has ever encountered before. But fear not; explanations are forthcoming. Before long, an armed man in a sailor suit comes to the door and insists that the four fliers accompany him to meet his boss. Our heroesí first sight of Robur comes in his own well-appointed cabin (much nicer than theirs), in which he is seated before a bank of windows looking out into the open sky. Aha! This must be an airship! Robur then takes his ďguestsĒ on a tour of his remarkable vessel, the Albatross, explaining how it works as he goes. It is 150 feet long, 25 feet in diameter, and capable of speeds well in excess of 100 miles per hour. It is powered by electrical engines, driving thrusting propellers at either end of the ship, and a veritable forest of smaller props pointing upward from the uppermost deck (to provide lift-- the Albatross lacks wings). The strange material from which the ship and everything in it is built is a sort of pressure-treated paper, impregnated with clay for structural strength, which is so lightweight that the entire vessel weighs only a few tons.

All very impressive, but why on Earth would a man build such a thing? Perhaps because he was a mad genius? Quite correct. And what would a mad genius do with the thing after he built it? Conquer the world, maybe? Surprisingly, no! Robur may be a mad genius, but he is not an evil one. All the man wants is to banish warfare from the world forever. And being the realistic sort of man that he is, he has come to the conclusion that the only way to bring about world peace is to force the nations of the world to disarm by confronting them with a new weapon against which all of theirs will be worse than useless. On the other hand, Strock being the man on the model of Mahan and Roosevelt (Theodore, not Franklin) that he is and Prudent being the wealthy-as-fuck arms manufacturer that he is, the two men will naturally feel compelled to oppose Robur with every fiber of their beings. Meanwhile, Evans will spend most of his time making a pest of himself by standing in Strockís way, and occasionally even trying to kill him, on the grounds that the G-manís stealthy plans for defeating Robur and the obvious affection brewing between him and Dorothy offend Evansís sense of gentlemanly honor. Along the way, the high points of the film will concern Roburís attacks on the American and English navies and his attempt to stop a civil war in Egypt by showing up at the scene of a major battle and stomping the asses of both sides.

Iíve often heard it said (to the extent that Iíve heard anything said about this movie) that Mathesonís script for Master of the World is remarkably close to the spirit, if not the letter, of Jules Verneís writing. Iíve never read either of the novels that served as the raw material for the screenplay, but on the basis of what I have read of Verneís work, I have to agree. And I must say, I think thatís most of the problem with Master of the World. Not to put too fine a point on it, Jules Verne bores the living shit out of me. His stories are almost completely devoid of story, and serve mainly to showcase, with the most offensive Gallic smugness, his scientific knowledge. But alas, poor Jules, he had the misfortune to be writing during the 19th century, arguably the period during which the discrepancy between scienceís opinion of itself and the actual state of its advancement was at its greatest. Quite simply, nearly everything Jules Vern knew-- nearly everything on which he spent most of the pages of his books expounding with the cloying, misplaced certainty of a medieval clergyman or a Hellenistic-age natural philosopher-- was wrong. And while nothing in Master of the World quite compares to the now hilariously bad marine biology of 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea, Matheson has taken pains to preserve quite a bit of Verneís half-baked science, while retaining the anemia of plot that Verne favored as well. In reference to the former, Iím thinking in particular of Verneís charmingly naive notion that electricity is a power source, rather than a means of power transmission. Like Nemoís Nautilus, the Albatross is powered by electricity, and is thus able to dispense with the huge weights of fuel that hobbled such wonders of 19th-century technology as the locomotive and the steamship. But electricity isnít merely out there in the world, waiting to be harnessed. It must come from somewhere-- a battery, a turbogenerator, a nuclear reactor, photoelectric cells. In other words, using electricity doesnít save you from having to lug fuel around, unless youíre carrying batteries instead, in which case you could be even worse-off from a weight perspective than you would be carrying fuel (just ask the engineers who spent decades struggling to develop a viable electric car before the invention of lightweight lithium batteries).

Normally, this kind of thing doesnít bother me, and indeed may even make me enjoy a movie more. But with so little in the way of story, and with such a large part of what story there is undermined by poor directorial decisions (see, for example, the scene in which Strock and Evans are hanging for their lives from ropes dangling below the Albatross as it races at treetop height over a sparsely wooded plain, during which the director inexplicably gives the lionís share of his attention to the ostensibly comic havoc that the shipís rapid maneuvering is causing in the kitchen), the attempts to dazzle us with pseudo-science take center stage by default. Were it not for the impressive-- if old-fashioned-- special effects, the inadvertently funny battle scenes (in which sailing warships fire their broadsides [the elevation of which is limited to only a few degrees] at a target hundreds of feet in the air and hit), and the delightful interplay between Priceís thunderous overacting and Bronsonís mummified underacting, Master of the World would be a very difficult film to watch indeed.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact