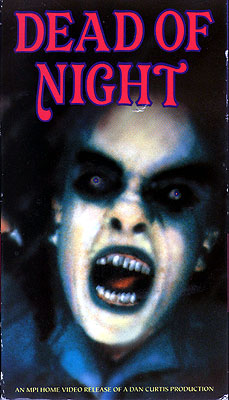

Dead of Night (1976/1977) **˝

Dead of Night (1976/1977) **˝

When Dan Curtis hit big with The Night Stalker in 1972, he wasn’t looking to launch a TV series— indeed, he turned down the offer from Universal Studios Television to run the show when his brainchild went weekly as “Kolchak: The Night Stalker” two years later. There’s some irony, then, in the fact that so many of the highly regarded made-for-TV horror films that Curtis produced and/or directed during the 70’s were actually failed pilots. The Norliss Tapes, Trilogy of Terror, Dead of Night— all were shot with an eye toward series production, but got the thumbs-down from the networks. Dead of Night’s failure to ignite is especially curious, because it was so obviously designed to piggyback onto Trilogy of Terror’s unexpected success as an ABC Tuesday Movie of the Week. Curtis brought back Richard Matheson to write the teleplay, again using his own work as source material. The individual tales were plainly chosen to demarcate the proposed series’ intended tonal and topical range— and Dead of Night too would culminate with a lone, frazzled woman battling a supernatural monster within the confines of her own home. And this time, Curtis threw in a paragraph of Serlingesque introductory narration to help even the dimmest, most unimaginative viewer get into the swing of things:

|

This is the Dead of Night. It has nothing to do with time. It can happen in sunshine or in the moonlight, in the best of weather or the worst, for the Dead of Night is a state of mind— that dark, unfathomed region of the human consciousness from which all the unknown terrors of our lives emerge. The Dead of Night exists in all of us, and no one knows at what strange, unexpected moment it will make itself known. And so, tonight, for your entertainment, three tales: one of mystery, one of imagination, and one of terror. |

“Second Chance” is the odd segment out here, in that Matheson adapted it not from his own writing, but from a story by Jack Finney, of Invasion of the Body Snatchers fame. I’m guessing it’s supposed to be the tale of mystery, but not in the whodunit sense. No, this is mystery of the “what the fuck just happened?!” variety, as an antique car enthusiast by the name of Frank (Ed Begley Jr., of Private Lessons and Transylvania 6-5000) goes on the weirdest joyride of his life. It starts when he buys a mid-20’s Jordan Playboy roadster from a local farmer (Dan Curtis regular Orin Cannon, who was also in Trilogy of Terror and Burnt Offerings) with the aim of restoring it to factory condition. That’s a pretty tall order, considering that the Playboy is in junkyard condition now, but Frank has time, skill, and determination on his side. While concluding the sale with the farmer, Frank gets a rather morbid earful concerning the car’s past. The old man acquired it as salvage one night in 1926, when its rightful owner killed both himself and his girlfriend while trying to cut across some railroad tracks in front of an oncoming train. Apparently it was sort of the Roaring 20’s equivalent of playing Chicken. The train must have just dinged the car, because it was still drivable once it was set back on its wheels. The passengers, however, were crushed when the Jordan landed upside down on top of them. Good thing Frank isn’t superstitious, huh?

It takes many months, but Frank eventually gets the old heap looking and running as good as new. On a lark, he even equips the Playboy with its original license plate, which was among the debris of miscellaneous accessories the farmer handed over along with the car proper. For the restored Playboy’s maiden voyage, Frank decides to drive into Creswell, the next town over— what would be about a ten-minute trek if he took the highway. Frank doesn’t take the highway, though. Instead, he drives into Creswell on the old county road, the way someone might have when the Jordan was brand new. Everything as close to period-perfect as possible, you see? And that, or so Frank reckons, is how he ends up where he does— or rather, when. For while he certainly arrives in Creswell, he does so on a summer night in 1926! Worse yet, he gets temporarily stranded there (or then) when some jerk speeds off in his car with a girl in the passenger’s seat. Frank tries to stop the thieves, but succeeds only in delaying them a moment. With no way to explain himself to anyone he might turn to for help, the lad just sneaks into the backyard of the couple who will later become his grandparents, and beds down for the night in a hard-to-see corner of the rear porch. Luckily, the timeline has straightened itself out by the time he awakens, and he’s able to get a ride home in the morning.

Is everything really back to the way it was before, though? Six months or so after his visit to the past, Frank meets and falls in love with Helen McCauley (Christina Hart, from Women and Bloody Terror and The Stewardesses). It’s odd that they never crossed paths before, what with this being such a small community, but Helen says she’s lived here all her life. One afternoon, she brings Frank to meet her grandparents (E.J. Andre, of Magic and Evil Town, and Ann Doran, from Kitten with a Whip and The Scarecrow), and it comes out over lunch that the lad enjoys fixing up antique automobiles. Would you believe Mr. McCauley has an old junker of precisely Frank’s favorite vintage in his garage? Sure you would. After all, Helen must have had some reason to imagine that her boyfriend would want to hang out all afternoon with a couple of septuagenarians, right? The thing is, though, Mr. McCauley’s car isn’t just any antique. It’s a 1920’s Jordan Playboy roadster, just like the one Frank rebuilt the year before. What’s more, McCauley kept all of its license plates down through the years, and the oldest is an exact match for the one on Frank’s lost Playboy, too. Weirdest of all (but probably also the explanation for everything) is an anecdote the old man relates about his and his vehicle’s youth. One night— it must have been 50 years ago now— he nearly got himself and the future Mrs. McCauley killed in a damnfool attempt to race a train across its tracks. At the last moment, he realized that he was just a few seconds too late to make it, and veered aside…

The tale of imagination is Matheson’s “There’s No Such Thing as a Vampire.” Alexis Gheria (Anjanette Comer, from The Night of a Thousand Cats and The Baby) strenuously disagrees with the assertion in the title. In fact, she’s fairly certain she’s dying of a vampire’s depredations. In any case, she awakens every day or two with a bloody wound on her throat, another shade weaker than she was the night before. The household servants are terrified. Only Karel the butler (Elisha Cook Jr., of Salem’s Lot and The Phantom of Hollywood) has the gumption to stay on, however angrily Alexis’s husband, Dr. Gheria (Patrick MacNee, from Masque of the Red Death and The Howling), berates the others’ cowardice. The villagers shun the Gheria house, and spend as little time out of doors after dark as they can manage. Eventually, even the doctor is forced to concede his wife’s supernatural persecution, but no matter how he and Karel search, they are unable to root out the vampire’s daytime hiding place. Fortunately, though, Gheria has a friend on the way— another medical man by the name of Michael (Horst Buchholz, of The Amazing Captain Nemo and The Savage Bees). Maybe with Michael around, the doctor will be able to get somewhere. The question is, exactly which “somewhere” is Gheria trying to reach? It happens that Michael and Alexis are rather friendlier with each other than is generally considered proper for a single man and a married woman, and the doctor isn’t half the fool they’ve taken him for. Maybe there’s no such thing as a vampire after all…

And finally, the tale of terror: “Bobby.” The title refers to a pubescent boy who drowned some months ago, apparently while playing among the surf-battered rocks below the sea cliff overlooked by his family home. His mother (Joan Hackett, from How Awful About Allan and The Possessed) has gone absolutely bugshit in the aftermath, refusing to believe that Bobby is really gone. Her husband, at the end of his tether, now welcomes the frequent absences from home that his travel-intensive job requires, and we’ll know him only as a disembodied voice over the telephone. During Dad’s latest trip out of town, Bobby’s mother makes a long-awaited breakthrough, but it’s a good news/bad news situation. The good news is, she finally admits to herself that her son is dead. The bad news is, she responds to that epiphany with a ritual invocation of the demon Euronymus, from whom she demands Bobby’s return. At first nothing happens, but an hour or two later, there’s a feeble knock at the front door. The rain-bedraggled boy on the doorstep (Lee Montgomery, of Mutant and Ben) looks exactly like Bobby, and the story he tells— something about a head wound, amnesia, and a family named “Breen” or “Green”— is just barely within the bounds of plausibility as an account of where he’s been all this time. Nevertheless, something isn’t right here. “Bobby” doesn’t know things that he certainly ought to if his memory has returned to him, and the questions he asks are either uncomfortably accusatory or disturbingly tactical in character. His behavior, moreover, is wild, erratic, and even cruel. Looks to me like there’s some Monkey’s Paw shit about to go down here…

All things considered, I think I would rather have had the series teased by Trilogy of Terror. Dead of Night’s implication that about one out of every three episodes would be in the vein of “Second Chance” is a turnoff for me, even if “Second Chance” itself is an inoffensive enough example of its form. Just the same, I think Dead of Night possesses sufficient merit to win over most fans of its more famous predecessor. “Second Chance” isn’t half as schmaltzy as the typical fantasy Americana yarn. It’s a mood piece more than anything, but the mood is nicely complicated, as befits a scenario in which someone accidentally meddles with destiny and comes out ahead. Ed Begley Jr.’s narration does a lot of the heavy lifting, conveying a mix of quiet wonderment, humble gratitude, and lingering unease. “There’s No Such Thing as a Vampire” exists mainly to serve as a delivery system for a wicked twist ending, but that turns out to be adequate justification for its presence here. Patrick MacNee had a knack for playing bastards above suspicion (witness his turn as Space Satan on “Battlestar Galactica”), and Dr. Gheria is one of his best. When the doctor shows himself for what he really is, it isn’t a case of the mask just slipping. This mask gets carefully and deliberately removed, folded into a prim and compact package, and then tucked fastidiously away to remain safely unmarred when the blood starts spurting. The way MacNee handles the transformation is so artful that I don’t mind the subgenre bait-and-switch that accompanies it one little bit!

But again in parallel with Trilogy of Terror, it’s the final segment that seals the deal in Dead of Night. Like Amelia’s Zuni fetish doll, Bobby is much scarier than one expects from the antagonist in a made-for-TV movie. Not least, this is because we’re never sure until the very end just what in the hell he is. He might be the child that he seems, come back wrong in response to his mother’s diabolical conjuring. He might be an entity from some demonic netherworld, sent to claim the souls of those who dare to impose upon Euronymus. Knowing Richard Matheson, he might even be the phantasmal personification of his mother’s own guilt. The actual answer turns out to be the most satisfying of all possibilities— which is to say, not quite any of those things, and yet also somehow all of them at once. The tightly circumscribed setting adds a complicating layer of claustrophobia to the already considerable horror of a mother being hunted by what seems to be her own child, and the fact that this is all happening inside the protagonist’s house contributes a dash of aggrieved hopelessness. After all, what the fuck is “escape” even supposed to mean on those terms? Or “victory” either, when the best possible outcome for Bobby’s mother is most likely to kill the very child whom she was so desperate to bring back? Overall, Dead of Night sits merely at the high end of okay, but “Bobby” in particular displays to more than fair effect the most startling and impressive feature of its era’s TV horror films. Even despite what ought to have been impossibly strict rules of engagement, they sometimes managed to be only slightly less vicious at heart than their infamous big-screen contemporaries.

This review is part of a B-Masters Cabal roundtable on horror anthologies. Click the banner below to read my colleagues’ contributions:

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact