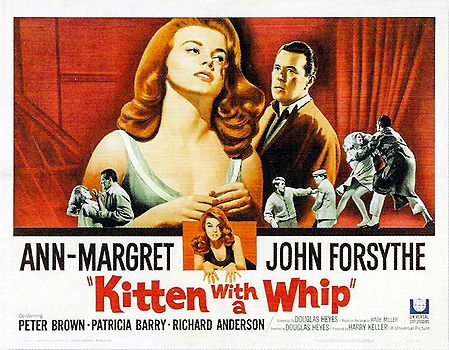

Kitten with a Whip (1964) ***˝

Kitten with a Whip (1964) ***˝

I really didn’t know what to expect when I sat down to watch Kitten with a Whip. That title, on a movie from the mid-1960’s, sounds like a roughie, but Kitten with a Whip was released by Universal, and the big studios didn’t make roughies. Some of the descriptions of the movie I’d read made it sound like a juvenile delinquent picture, but 1964 seemed awfully late for one of those— later even than the infamously tired and tardy The Beatniks! Others suggested a florid melodrama of the “Tennessee Williams by way of Douglas Sirk” school, but I knew that Kitten with a Whip had been used in an episode of “Mystery Science Theater 3000,” and I couldn’t imagine Mike and the Bots taking on a film like that. One possibility that never crossed my mind was that Kitten with a Whip might be a 60’s psycho-horror mutant seemingly informed by all three of the aforementioned traditions, but that’s just what this movie turned out to be. Instead of a post-menopausal lady, its deranged villainess is a teenaged girl who associates with a band of violent beatnik nihilists. Its TennesSirkian central conflict pits her against a man whose marriage is collapsing under the strain placed on it by his career in politics— meaning that he has much to lose from public embarrassment— and his life goes (or at any rate, threatens to go) baroquely to shit when he attempts to perform a good deed on her behalf. And most surprisingly, the means whereby the girl torments her hapless would-be benefactor are as thoroughly soaked in sexual sleaze as a major-studio movie could get away with at the time.

Seventeen-year-old Jody Dvorak (Magic’s Ann-Margret) is on the run. It isn’t clear yet whence, whither, or why she’s fleeing, but the hour (the middle of the night) and her mode of attire (what looks like a juvie-hall nightgown) are both suggestive. Eventually, the girl finds herself in an upscale neighborhood in what I take to be the suburbs of San Diego, where she stumbles upon a house with nearly a week’s worth of daily newspapers scattered across the front lawn. Score! Jody breaks into the house, and beds down in a room decorated with an array of old stuffed animals.

It turns out, though, that the owners of Jody’s hideout aren’t all on vacation or whatever after all. Man of the house David Stratton (John Forsythe, from Cruise into Terror and The Deadly Tower) has just been too busy laying the groundwork for his forthcoming Senatorial run to notice the accumulating papers, and with his wife, Virginia (Audrey Dalton, of Mr. Sardonicus and The Monster that Challenged the World), out of town visiting her family for the week, he’s had nobody but the nosy neighbors to enforce an acceptable standard of housekeeping. Only an hour or two after Jody has fallen asleep, David comes home from an evening out on the town with his friends, Grant (Richard Anderson, from The Night Strangler and The Stepford Children) and Vera (Patricia Barry, of The Beast with Five Fingers and Twilight Zone: The Movie). He doesn’t notice the adolescent stranger occupying the other bed, but goes straight to his own room for what remains of the night.

Stratton is rather more observant the following morning, and he naturally has a few questions for Jody when she wakes up. The girl tells David that she ran away from home to escape an abusive father, and she has the welts on her back to substantiate the story. Obviously she doesn’t feel like she can go home, but she has some friends out of town whom she could stay with if only she could get herself onto a bus. Jody has no money, though, and a teenaged girl walking around in a nightgown is going to attract attention even in southern California. Moved by his uninvited guest’s tale of woe, David agrees to buy her some presentable clothes and a bus ticket, and even to give her a bit of cash to cover unforeseen contingencies at the far end of her journey. The shopping trip almost gets Stratton into trouble, for he happens to run into a friend of his wife’s at the store. That friend immediately barges into his transaction with the clerk, demanding to see what David is getting for Virginia, and raising a well-intentioned fuss when she sees that everything is the wrong size. Stratton gets away only by pleading a desperate aversion to shopping and an equally desperate desire to get out of the boutique as quickly as possible.

Upon dropping Jody off at the bus station, David meets Grant for lunch. The restaurant has a television set in the dining room, and Stratton is taken aback to say the least when he glances up at it just as the screen fills with Jody Dvorak’s face. According to the news, every element of the story she told him that morning was a lie. It wasn’t a brutal home life she was trying to escape, but a reform school— and she did a lot of damage to one of the matrons while making her getaway. Still, that slippery delinquent should be halfway across the county by now, and David stands little chance of ever seeing her again. He figures he might as well keep quiet about being played for a chump, put Jody Dvorak out of his mind, and concentrate on preparing for tonight, when Grant will introduce him to Mr. Varden (Patrick Whyte, of Weekend with the Babysitter and The Hideous Sun Demon), a local fat cat whose support could make or break Stratton’s chances of winning a seat in the Senate.

So you can imagine David’s confoundment when he comes home from the restaurant, and finds Jody back at the house waiting for him. Evidently she had no fixed schedule to keep in her escape plan, and decided that she really ought to thank David appropriately— or rather, inappropriately— for all his help. When he instead confronts her with what he learned from the TV news, Jody turns nasty, scratching his face hard enough to leave marks and threatening to accuse him of rape if he calls the cops on her. Worse yet, the latter issue is still unresolved when Virginia calls on the phone to announce that her return flight will be arriving late that night, and when the nosiest of the nosy neighbors drops by with a homecoming bouquet for Mrs. Stratton. So many potential avenues for exposure and disgrace, so few options for covering them all…

The worst is yet to come, though. Not content with trying to blackmail David out of turning her in and into sleeping with her, Jody takes advantage of the lady next door’s intrusion to phone a few friends and invite them over for a party at the Stratton place. That’s tonight she’s talking about, and she’s not interested in anything David has to say about appointments to hobnob with rich campaign donors. If he knows what’s good for him, he’ll invent some cover story and back out of his date with Grant, Vera, and Varden. It’s when Jody’s pals show up that the trouble really starts, however. Buck (Skip Ward), Ron (Peter Brown, from Chrome and Hot Leather and Foxy Brown), and Midge (The Strangler’s Diane Sayer) aren’t just teen hoodlums like Jody. No, the boys (I think they’re actually supposed to be noticeably older than her, instead of being simply the usual 30-year-old teenagers) make a living smuggling drugs across the border from Tijuana, and while they’re less heavily armed, they’re every bit as ready to resort to serious violence as today’s international dope-runners. It’s bad enough merely to have this bunch in the house, working their way through the liquor cabinet. But as Stratton soon learns to his horror, Buck and Ron have a pickup to make tonight, and it’s becoming increasingly obvious that they mean to include him in the venture. David’s efforts to forestall any such thing send the situation spiraling out of control. There’s all manner of potentially deadly excitement in his immediate future— and that’s before Jody and her criminal friends start turning on each other!

I don’t think I’ve ever seen quite this mix of elements come together in quite this way before, nor can I recall seeing a couple of them handled with such sophistication in a film of this vintage. Certainly Kitten with a Whip is nothing I would ever have expected from Universal! It’s going to take a conscious effort of will to do more than just repeat myself over and over, because my overwhelming reaction is blunt astonishment that there could be such a thing as a sex-scandal melodrama that’s also a juvenile delinquent movie that’s also a psycho-horror film that comes this close to being a roughie. What’s perhaps even more remarkable is that Kitten with a Whip wears all those hats in a pretty becoming fashion.

Obviously the baseline requirement for a sex-scandal story is that it be both sexy and scandalous, and Kitten with a Whip definitely has that much covered. Writer/director Douglas Heyes (stepping up from television to feature film for the first time) displays an extraordinarily acute understanding of the mechanics of temptation. David Stratton would never think of cheating on his wife, no matter how mutually unsatisfying their marriage has become— until he’s offered the chance to do so on the most unacceptable terms imaginable. And even then, if you asked him, he’d tell you he wasn’t interested in an affair, let alone an affair with a girl young enough to be his daughter. He’d be telling the truth, too, so far as his rational mind was concerned. But the Imp of the Perverse is not rational. Jody may have to blackmail David into doing anything friendlier than to hand her over to the cops once he learns the truth about her escape from juvie hall, but there’s no mistaking that some secret, hidden part of him wants to succumb to her wiles, and is pleased to have her extortion as a pretext for keeping company with her. Mind you, it doesn’t hurt that it’s Ann-Margret pushing for Stratton’s damnation. I’ve always been largely impervious to the charms of the major mid-century Hollywood bombshells, but Ann-Margret is in a class apart from Marilyn Monroe and her imitators. More than anything, she’s not so glaringly affected. Her sex appeal feels intrinsic to who she is (or at least to who she’s playing), whereas the rest of that bunch put me in mind of aliens from a sexless planet attempting to counterfeit human arousal as part of an experiment in xenoanthropology.

The relative naturalism of Ann-Margret’s performance is also an asset to Kitten with a Whip in its guise as a psychological horror film. Jody has mood swings, you see, nearly extreme enough to be mistaken for multiple personalities. One moment, she’s charming and personable, just as one often sees in a high-functioning psychopath. Then the next, she turns irrationally vicious, harming those who were trying to help her and actively working against her own interests, apparently out of sheer contrariness. There’s no warning when the switch will trip one way or the other, either, which must have put a tremendous strain on Ann-Margret’s acting ability. Her success in bearing that strain is crucial to the movie’s effectiveness. It makes all the difference between a Jody Dvorak who is frighteningly unpredictable and one who is just comically incoherent. Notice also that Jody remains scary even though she poses no credible physical threat to David. To the extent that Kitten with a Whip reads as a horror film, it’s one of the rare breed which understands that a person determined to ruin your life is only trivially less menacing than someone seeking to end it. Such a villain is apt to get deeper under an unimaginative viewer’s skin, too, since an enemy bent on sabotaging relationships and destroying reputations is closer to most people’s life experience than a maniac with a garden tool.

Now so far, I’ve been talking about Kitten with a Whip’s verging on the status of a high-class roughie as if it were something separate from the movie’s melodrama and horror aspects, but that isn’t exactly true. Better to say that the roughie qualities emerge from the intersection of the other two strands, as the natural result of Jody’s unusual position as both villain and lust-interest. Fucked-up attraction to monstrous women is a big part of the roughie’s stock in trade, the flipside of the genre’s catering to masculine sexual power fantasies. Kitten with a Whip’s frankness about such subjects must have been shocking indeed for mainstream audiences in 1964, when seeing anything comparable usually required a trip to the skeezy side of town and a commitment to spend a couple hours surrounded by heavy-breathing men in filthy raincoats. What non-pornographic precedent there was for the forthright depiction of weaponized sexuality could be found almost exclusively in European imports, and it may well be that Universal were pitching this movie to the same audiences that turned out for the works of Roger Vadim and his ilk. Modern viewers who come looking for a big-budget Olga’s House of Shame will be disappointed, of course, but those with more realistic expectations will most likely be impressed by what Heyes gets away with in Kitten with a Whip. Perhaps the best way of looking at it is to think of this movie picking up where pre-Code Hollywood left off.

What impressed and surprised me most, however, was how Heyes approached Jody’s social circle. Don’t get me wrong now. Kitten with a Whip is as ludicrous as any movie ever made when it comes to youth-lingo dialogue, and its portrayal of the beat counterculture is more alarmist than most. But almost uniquely in my experience, it’s entirely serious about treating the beatniks as truly a counterculture— as people who don’t merely reject the values of mainstream society, but posit values of their own to replace them. The main object may be to establish that these kids are fucking crazy, but whenever Buck holds forth on the philosophy that motivates him (and, to a lesser extent, his friends), there’s a clear sense that he believes in what he’s saying, and has put in a lot of intellectual effort to get there. The basis of Buck’s reasoning will sound familiar to students of and participants in subsequent movements of youth rebellion, too. It’s his contention that his elders forfeited all credibility as arbiters or exemplars of wisdom or morality the moment they began planning seriously how best to incinerate the world in atomic holocaust. The individual characterizations of Jody and her friends are also worthy of note, covering a spectrum of personality types that rings true for practically any counterculture: disaffected intellectuals at one end, thugs and crazies at the other, and jaded thrill-seekers in the middle. It should be obvious that this is a great deal more sophisticated than most cinematic portrayals of juvenile delinquency, even if it seems weirdly out of touch with what youth culture was doing in the mid-1960’s. I don’t recall many beatnik movies from the movement’s 1950’s heyday that got it half this well, though, so better late than never.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact