Magic (1978) ***½

Magic (1978) ***½

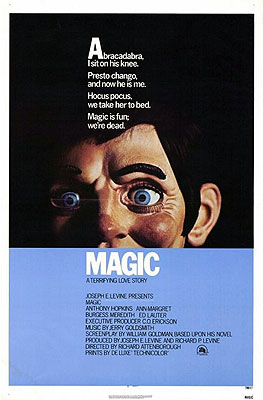

If you were a child in the late 1970’s, you might just possibly remember a certain television commercial— assuming, that is, that you weren’t hiding behind the sofa every time it came on. The only image on the screen is a ghoulish-looking ventriloquist’s dummy, toward which the camera glides ever closer as spooky violins squeal on the soundtrack. In a grating, high-pitched, Vaudeville-accented voice, the dummy starts to chant:

Abracadabra! I sit on his knee…

Presto! Chango! And now he is me!

Hocus-pocus! We take her to bed…

Magic is fun! We’re dead.

At that point, an announcer comes on to promise “a terrifying love story.” Some might have been skeptical that a love story could be terrifying, but that goddamned dummy sure as hell was! That commercial was the kind of thing that would stick with you forever, even if you forgot— as I did— what movie was being advertised. We live in the YouTube Age of Wonders now, though, so no bit of media flotsam, however ephemeral, need ever be truly forgotten. Somehow or other, something led me to that horrid old commercial recently, and thence to the knowledge of what film I should be looking for to see if it could possibly measure up to its ad campaign. Incredibly enough, Magic does.

A sick old man by the unlikely name of Merlin (E. J. Andre, of Haunts and Evil Town) lies abed in a cluttered, shabby urban apartment, seemingly waiting for something. A much younger man (Anthony Hopkins, from The Wolfman and The Silence of the Lambs) enters, and begins describing with visibly false satisfaction a performance of some kind. It gradually becomes apparent that the younger guy is Merlin’s protégé, Corky, and that the act he’s bullshitting was his own debut as a nightclub magician. Soon enough, though, Corky breaks down and admits that he bombed like Jimmy Doolittle. Oh, he did all his tricks just fine, but the crowd couldn’t be bothered to notice him at all until he lost his temper and stormed off the stage after berating them for a bunch of ingrates. Merlin asks if Corky wants to keep going, which he says he does. In that case, the old man counsels, he’s going to have to find himself a “charm.” “What?” Corky asks. “You’ll think of something,” Merlin assures him.

One year later, a television producer named Todson (David Ogden Stiers) arrives at the very same club where Corky humiliated himself, heeding the summons of Ben Greene, the proprietor (Burgess Meredith, from Torture Garden and Burnt Offerings). Greene is a talent agent as well as a club owner, and he has an act that he wants Todson to see. Would you believe he’s talking about Corky? Greene waves away Todson’s protests that magic acts never work on television, but at first it looks like Corky is as hapless onstage as ever. The strongest interest he attracts is that of a heckler somewhere in the back of the room, whose taunting becomes so persistent that Corky looks like he’s losing his cool again. “You think you could do better?” the flustered magician demands; “Sure I could!” rebuffs the heckler. At that, Corky charges offstage— only to return a moment later carrying a ventriloquist’s dummy. You got it. Corky’s been heckling himself as the lead-up to the real show, in which he and the dummy— Fats, he calls it— squabble their way through a far more adept and compelling display of conjuration. And just in case Todson fails to spot the implications for his TV station, Greene explicitly lays out the secret to Corky’s newfound success. Magic is about misdirection; the reason it fails on television is because you can’t misdirect the camera. Corky’s act circumvents that weakness by employing a second layer of misdirection that will capture the attention of TV’s all-seeing eye.

With Todson’s support, Corky begins making the rounds of the TV variety shows, quickly becoming a household name. Complications arise, however, when Todson decides to offer Corky his very own series. For insurance purposes, it’s standard practice for the station to submit its would-be stars to a medical examination. A television production season can be pretty grueling, after all, and there’s too much money on the line to risk the star of the show having a heart attack or a nervous breakdown with five episodes left to shoot or whatever. Corky adamantly refuses to cooperate with the exam, though. When Greene tries to reason with him, the magician cites “principle,” but never quite gets around to elucidating what principle he’s talking about. You’ll have some inkling of what Corky is really afraid of, however, from the first time you see him talking to Fats backstage. What probably started as an innocent method of developing the dummy’s character and keeping in practice throwing his voice has taken on a decidedly sinister aspect now. Indeed, the conclusion that Corky’s head is no longer screwed on quite straight is practically inescapable. In any event, Todson and his lawyers aren’t budging on the medical exam, so Corky goes AWOL, taking a cab out into the countryside without a word of notification or explanation to anyone, and tipping the driver generously to secure his silence.

Impulsive though Corky’s flight might have been, it was by no means random. The little community where he has the cabbie drop him off is his hometown, where he hasn’t set foot since he came of age. Furthermore, the woman whose converted boathouse he arranges to rent is Peggy Ann Snow (Kitten with a Whip’s Ann-Margret), the girl on whom he had an unrequited crush all through high school. Corky’s object seems to be to test how badly he really wants fame and success by investigating how his life might have been without them.

Rather surprisingly, the first thing Corky discovers upon coming home is that Peggy Ann wasn’t half as oblivious to him as he believed. It’s just that this is a small town with old-fashioned values; around here, guys are supposed to ask girls out, and never the other way around. If Corky had ever worked up the nerve to say something about his feelings, he’d have had what his teenaged self wanted decades ago. Unfortunately, the prospects for a second chance are limited by the fact that Peggy Ann hasn’t just hung around pining for Corky all this time. Indeed, she’s married now— and although her husband (Ed Lauter, from The White Buffalo and The Town that Dreaded Sundown) is away on a hunting trip when Corky arrives, Duke will be back in just a few days. He’s the jealous type, too.

In the final assessment, though, neither Duke nor Greene nor Todson’s lawyers are Corky’s real problem. No, his real problem is the little wooden homunculus shut up in that case he carries with him everywhere— or rather, his problem is what Fats has come to represent. The dummy is a repository for all Corky’s negative emotions: the self-loathing born of a lifetime of failure, the resentment of breaks not offered, the regret of chances not taken. At the same time, however, Fats also embodies whatever strength, charm, drive, and self-confidence Corky ever had. So when Corky and Peggy Ann fall in love anew during their few days alone together; when Duke’s return exposes how unhappy the couple’s marriage really is; and when Greene tracks his wayward star down despite all his precautions to the contrary, it’s Fats and not Corky who knows just what to do.

There are basically two strains of ventriloquist’s dummy movies: the kind in which the dummy is animate, sentient, and most likely evil, and the kind in which it symbolizes the fragmented personality of its owner. Although Magic’s title and advertising campaign seem to promise the former, it is actually situated squarely within the latter tradition. I can just barely imagine how some viewers might come away disappointed because of that, but this film is such a tour-de-force of 60’s-style psycho-horror that it doesn’t seem likely. Nor is that line from the commercial— “a terrifying love story”— merely a plea from some genre snob in Marketing that we take Magic as something other than a fright film. Magic is indeed out to scare for all it’s worth, even if it takes its time in getting to that point. It’s like the supper scene from the second act of Psycho (and its aftermath, of course) expanded into an entire movie, and with the interpersonal dynamic flipped to make Norman the viewpoint character.

That last part, I think, is why Magic is at such pains to develop the relationship between Corky and Peggy Ann. We know before Corky ever sets foot in the old hometown that there’s something seriously wrong with him, but it seems at first like he could get better. More than that— it seems at first like reconnecting with his past could make him better by helping him to find peace in the present. And the way Anthony Hopkins plays Corky hits that Basset hound sweet spot of pathetic-yet-lovable. You want the guy to succeed, whether that means embracing his new career opportunities, or whether it means chucking everything to give Peggy Ann a reason to put her marriage out of its misery. Ann-Margret, meanwhile, gives us enough sense of her somewhat underwritten character to indulge Peggy Ann’s second-chance fantasies, even though doing so is tinged with amply justified unease. Having this kind of rooting interest in the central characters’ lives and relationship puts an unusual spin on things when the part of Corky’s psyche that expresses itself through Fats finally turns homicidal. At the same time as it becomes most truly horrific, Magic also blossoms into tragedy— not just “a terrifying love story,” but also a deeply sad story about multiple murder.

This inexcusably tardy review was supposed to be part of the B-Masters Cabal’s roundtable on movies about deadly dolls. The banner below will take you to the work of my colleagues who handed in their assignments on time:

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact