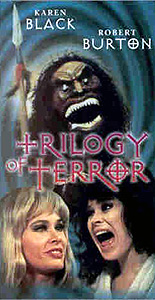

Trilogy of Terror (1975) ***

Trilogy of Terror (1975) ***

Made-for-TV movies don’t get a whole lot of respect, and with good reason— the great bulk of them don’t deserve any. This is doubly true in the case of made-for-TV horror movies; the rules of engagement, as it were, are so restrictive on broadcast television that it’s virtually impossible to make a worthwhile horror flick while playing by them. I mean, think about it. Any horror film worth its salt is designed to elicit some sort of uncomfortable emotion from its audience: fear, shock, revulsion— unease at the very least. TV producers, on the other hand, fear nothing on Earth more than audience discomfort. Those foolhardy filmmakers who attempt to work in the field of made-for-TV horror are thus usually forced to try to scare their audience without doing anything scary, to shock them without doing anything shocking, to repulse them without doing anything repulsive. So it is only to be expected that only a tiny handful of TV horror movies have anything like a following after their initial release, and that most of those that do earned their followings precisely because they were so fucking awful. Dan Curtis’s Trilogy of Terror is probably the single most striking exception to this rule. Not only do lots of people remember it fondly even today, most of those people will tell you the final segment of this three-part anthology flick is one of the scariest things they’ve ever seen. And while I’m sure most of that can be explained by the average commentator having first seen it when he or she was between five and ten years old, the fact remains that this movie stands head and shoulders above the norm for broadcast horror.

All three segments are derived from short stories by Richard Matheson, who, as my tiny handful of longtime readers will surely have figured out by now, is one of my all-time favorite authors. The first story, “Julie,” is based on a wonderfully mean-spirited little tale called “The Likeness of Julie.” College boy Chad Foster (Robert Burton) is standing out in front of one of the university buildings, talking to a friend of his, when his literature professor, Julie Eldridge (Karen Black, from Killer Fish and The Pyx, who plays a central role in each of the three stories) walks by on her way to class. Julie Eldridge is young for a college professor, and is one of those women who might possibly be attractive if only she didn’t strive so hard not to be, but even so, Chad is a bit taken aback by the thought that suddenly shoots across his mind: “I wonder what she looks like underneath all those clothes...” Later that day, in Julie’s classroom, his mind’s unbidden question to itself is all Chad can think about; by the end of the period, he has made up his mind to ask her out. Julie rebuffs him at first, reminding him that teachers are not permitted to date their students, but Chad persuades her with unseemly ease, needing only to ask how anyone would ever find out if both of them kept their mouths shut.

But there’s an unhealthy undercurrent to Chad’s newfound romantic interest in his professor. That night, he tracks Julie to the house she shares with another young teacher, and spies on her through the window as she gets ready for bed. Chad goes rather farther when the night of their date actually rolls around. The scheming student takes Julie to a drive-in movie (note that the “French vampire film” they’re supposedly seeing is really Dan Curtis’s earlier The Night Stalker), and when he goes to the snack bar to get himself and his teacher a couple of Cokes, he drugs Julie’s glass before bringing it back to the car. Once the drug takes effect, Chad leaves the drive-in, and takes Julie to an out-of-the-way motel, where he rapes her and takes scandalous, pornographic photos of her. The idea here is that Chad will be able to use these photographs to retaliate against Julie if she tries to turn him in— remember, it’s the mid-1970’s, and a court in those days might plausibly interpret the photos as evidence of a consensual sexual relationship between the two of them, in which case Julie’s career as a teacher would be over. The next day, Chad gets together with Julie to show her the pictures, and thus begins three solid months’ worth of kinky, extorted sex. The thing is, though, that there’s more to Julie than Chad realizes. And unfortunately for him, he won’t figure out just how much more until the day his “victim” tells him she’s grown bored with him. Wait a minute— just who is exploiting whom here, anyway...?

Next up is “Milicent and Therese,” and I’m really not sure which of Matheson’s stories it’s based on— in any event, it isn’t one that I’ve read. Milicent (Karen Black again) is a dowdy, severe woman who seems much older than she really is. She lives in the family mansion with her sister, Therese (also Karen Black, in a blonde wig that couldn’t be any less convincing if the hair and wardrobe people had designed it that way), and the two sisters don’t like each other one little bit. Therese is, to put it mildly, a woman of loose morals, and apparently an occult hobbyist too. Milicent, on the other hand, is extremely religious in a daffy, Protestant literalist sort of way, and it is her opinion that her sister is actively in league with the devil. Milicent also blames Therese for the death of their father, whom she believes Therese seduced when the sisters were teenage girls. Milicent might even be right about her sister’s relationship with their old man. And when Therese’s boyfriend, Thomas Amman (John Karlen, from House of Dark Shadows and Daughters of Darkness), stops by one evening looking for his absent mate, Milicent fills him in on every vile, immoral thing she believes Therese is caught up in. Amman initially seems to believe Milicent’s tirade reflects more on her than it does on her sister, but then again, we won’t be seeing him around anymore after that, either.

Thomas Amman isn’t the only one Milicent has been defaming Therese to. Her doctor, Chester Ramsey (George Gaynes, of Slaughter’s Big Rip-Off and The Boy Who Cried Werewolf), also gets an earful when his patient calls to complain about what Therese did in retaliation for her sister’s loose tongue. Ramsey makes arrangements to come by the house the following afternoon, but when he gets to the house, Milicent is out and Therese is in. And because it could scarcely be otherwise, Therese tries to seduce Dr. Ramsey when he talks to her in an effort to get her side of the story. The resulting clash between the sisters is the last straw for Milicent, and she resolves to use Therese’s own weapons against her. Following the instructions in one of her sister’s books, Milicent makes herself a voodoo doll, and the next time he calls, she tells Ramsey that she’s arrived at a way to deal with Therese once and for all. Of course, we B-movie veterans are thinking this may be more complicated an operation than Milicent realizes— the two sisters have never yet appeared onscreen at the same time, after all...

For the finale, Trilogy of Terror brings out the big guns. “Amelia” is adapted by Matheson himself from a story called “Prey,” which is among his very best— this segment is the real reason anybody cares about this movie today. The titular Amelia (everybody give it up for Karen Black one mo’ time...) is a single woman who’s gotten a rather late start on setting up a life of her own. Closing in on 30, she’s only just recently moved out of her clinging, controlling, manipulative mother’s house, and gotten herself an apartment in what probably seemed like a pretty stylish building in 1975. She’s also finally managed to get herself a serious boyfriend, an anthropologist named Arthur Breslow. Tonight is Arthur’s birthday, and Amelia has found just about the coolest imaginable present for him: a genuine Zuni fetish doll, called “He Who Kills.” According to the little brochure that came with the hideous, snaggletoothed little monster, He Who Kills is the final resting place of the soul of a fierce Zuni warrior, and the gold chain the doll wears around its waist is there to keep that soul safely contained. I’d certainly be impressed if my girlfriend gave me one of those. There’s just one problem with Amelia’s plan for the evening. It’s Friday night, and Friday night is traditionally reserved for hanging out with her mom. When Amelia calls her mother to back out of their engagement, the old lady shows us why her daughter was so thrilled to move out of the house in the first place. The moment Amelia opens her mouth, the head-games begin. By the time she gets off the phone with mom, Amelia has been successfully guilt-tripped into calling Arthur, and backing out on her date with him.

All in all, it makes for a very stressful evening, and once all her calls are made, there’s nothing in the world Amelia wants more than a nice, soothing bath. She isn’t going to get it, though. Amelia didn’t notice at the time, but when she set He Who Kills down on the coffee table rather vigorously after the high-pressure talk with her mother, the clasp holding the chain around its waist came loose. Amelia does notice that the doll is gone from the table when she walks back into the living room after turning on the faucet for the tub. I think you see where this is going...

Were it not for “Amelia,” Trilogy of Terror would probably be just as utterly forgotten as most of its TV-movie contemporaries. “Milicent and Therese” is tepid and predictable in that usual TV way, and “Julie” doesn’t hit anywhere near as hard as it should. The latter story loses a lot of its effectiveness (as compared to Matheson’s original) due to the way “The Likeness of Julie’s” psychological angle is left mostly by the wayside. The print version of the story spends most of its time in the Chad character’s head, and derives most of its kick from the fact that he’s horrified by his own behavior, but somehow can’t seem to stop himself. In the film version, however, Chad just comes across as a huge, contemptible asshole. But with “Amelia,” well, here we’re on to something. The strange thing is that, while I was watching it, I couldn’t make up my mind whether what I was seeing was unbelievably, hilariously stupid, or twenty of the finest minutes in the mostly pretty sorry history of horror on the small screen. Now that I’ve had a chance to think about it for a while, I think it somehow manages to be both at the same time. There’s just something inherently goofy in the spectacle of a grown woman pretending to wrestle with a wooden doll less than two feet high, and if the doll in question is supposed to be making distorted jabbering noises like the yeti in Shriek of the Mutilated the whole time, the effect is only intensified. But that fucking little doll is still creepy as hell, and as silly as “Amelia” is, it works anyway, in a way that all those miserable, pathetic Puppet Master movies only wish they could. And what’s more, the twist ending is great— much better than those of the preceding two stories, one of which is painfully obvious from the get-go and the other of which is handled in such a way that it doesn’t make a whole lot of sense. I wouldn’t say “Amelia” is as scary as it is widely reported to be, but it would make for a respectable showing from any horror anthology, even in a theatrical context. In the context of broadcast TV, you have to wonder how it made it past Standards and Practices at all!

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact