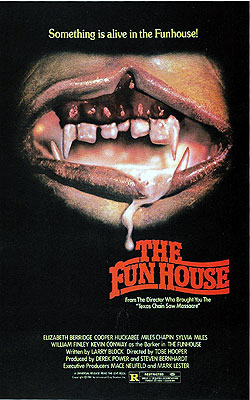

The Funhouse (1981) **

The Funhouse (1981) **

The trouble with starting out by concentrating on a given filmmaker’s best work is that sooner or later, you find yourself stuck with just the lesser stuff. And that, or so it would appear, is where I am now with Tobe Hooper. Having covered his early masterpiece, his impressive if uneven bids for a career in the Hollywood mainstream, and his underappreciated flawed gem, I fear it’s nothing but clunkers, junkers, and stinkers from here on out. The Funhouse is either one of Hooper’s weaker clunkers or one of his stronger junkers. It completes his loose trilogy of grimy movies about Deep South psychos, which famously began in Texas, then continued in Louisiana, and now skips over the Mississippi and Alabama panhandles to conclude in Florida.

The Funhouse begins in the tiredest possible way, with a sequence that genuflects toward both Halloween and Psycho. Eleven-ish Joey Harper (Shawn Carson, of Something Wicked This Way Comes) plays a pervo prank on his teenaged sister, Amy (Elizabeth Berridge), donning a rubber mask and pretending to attack her in the shower with a toy knife. This is not a smart way for a kid to treat the girl on whom he’s counting for a ride to the carnival tomorrow afternoon, and Amy assures him that the refusal of any such transport will be only the beginning of her vengeance. There’s no point in Joey turning to their parents, either, because Dad (Jack McDermott, from Primal Rage and The Final Countdown) doesn’t want either of the kids hanging around that place. It’s the same carnival that set up last year in Fairfield County, where two girls turned up dead in the adjoining woods soon after it packed up and hit the road again. No firm evidence ever linked the deaths to the carnival, but the Harper household is no court of law, and the old man’s evidentiary standard for the safety of his children is considerably lower than “beyond a reasonable doubt.” Mind you, neither Amy nor Joey intends to let their father’s interdict stand in the way of a good time. Amy has a date tonight with Buzz (Cooper Huckabee, of The Curse and The Pom Pom Girls), the mechanic from the local garage and filling station, and although the official story is that they’re going to the movies, the actual plan involves ferris wheels, cotton candy, and disappointingly small prize teddy bears. Joey, meanwhile, impulsively decides to pay his own nocturnal visit to the carnival via the time-honored route of his bedroom window and the big, old tree in the back yard.

Amy gets cold feet, though, when her father offhandedly bothers to explain the reason for his anti-carnival stance. When Buzz arrives to pick her up, she even asks him if maybe they really could go to see a movie instead. Buzz isn’t having it. Not only is his heart set on the fair, but he’s also agreed to give a ride to his friends, Liz (Largo Woodruff) and Richie (Howard the Duck’s Miles Chapin). This is the first Amy has heard of any plans to double their date, and she is pissed, regardless of the outcome on the carnival question. Other things she didn’t sign on for, but is apparently getting anyway, include dope-smoking in the car and mean-spirited jokes about cruelty to animals. By the time the foursome arrive at the carnival, Amy is visibly rethinking the whole idea of dating Buzz. But Joey, for his part, might have even less fun getting to the fair. Not only does he have to walk, but the one person who offers him a lift turns out to be a gross, creepy weirdo who speeds off without him after threatening him with a hunting rifle. The gun isn’t loaded, but Joey doesn’t find that nearly as funny as the man aiming it at him.

This being a horror movie, it’s pretty much inevitable that the carnival is vaguely sinister from jump. For example, I realize that these things are usually family enterprises, but the resemblance among the various barkers at this one is positively eerie (probably because they’re all played by Kevin Conway, of Lawnmower Man 2: Beyond Cyberspace). The hoochie-coochie tent is extra-foul (maybe even as foul as the real thing), with unhealthy-looking strippers and spectators who look to a man like their stepdaughters secretly hate kissing them goodnight. The freak tent, while it comes up short in quantity, features some truly ghastly human oddities in bottles of formaldehyde, along with some extravagantly malformed cows that might be even worse on account of their being still alive (and real!). Madame Vera the fortune teller (Sylvia Miles, from Violent Midnight and The Sentinel) makes the kind of ominous prognostications one comes to expect in this genre. Magician Marko the Magnificent (William Finley, of Silent Rage and Eaten Alive) puts on an unsettling act in which the climax is a staged “fatal” accident. But the most off-kilter thing at the fair is the funhouse. It’s way too big, for starters. While the rest of the attractions could be dismantled and hauled away aboard a convoy of flatbed trailers, the funhouse makes no physical sense unless we assume that it was converted at significant expense from a permanent structure that was already standing on the land where the carnival set up shop. The exhibits inside it are mainly the cheap crap you’d expect from such an establishment, but a few of them leave you wondering if perhaps they didn’t start off being the carnival owner’s grandma or something. And beyond that, the hulking, gangling carnie in the Frankenstein’s Monster mask (Wayne Doba) who helps the punters into the trolleys and sets them in motion somehow just isn’t right. Either despite or because of all that, Richie gets the goony idea to sneak back into the funhouse shortly before closing time, so as to spend the night there. And incredibly, he talks not just Liz and Buzz into doing it with him, but Amy too! Meanwhile, Joey— who’s been keeping surreptitious tabs on his sister for at least an hour or so— stays after closing time as well once he figures out what Amy is doing. He ends up having his parents called on him, however, after an encounter with something horrible leads to his discovery by the carnival proprietor and his family.

Speaking of horrible encounters, Amy and the others witness one of their own through the ill-fitting floorboards of what must have been a veranda when the funhouse was still whatever it was built to be. The carnies have turned the shed-like space below into a sort of office; it’s probably the most private spot on the premises as things currently stand. Said office is brought to the stowaways’ attention when they hear Madame Vera and the guy in the Frankenstein mask enter it from some other part of the building. They need the privacy because Frankencarnie intends to pay Vera to fuck him— while he’s still wearing the mask, no less. The masked man ejaculates before he’s even taken off his pants, however, and their dickering over a refund becomes so heated that he seizes the fortune teller, and strangles her to death. Naturally, Amy and her companions completely lose their stomach for after-hours trespassing when they see that, and turn their full attention to the question of how to leave the funhouse without revealing that they were ever in it. At that point, the funhouse barker walks into the office below, and the scene takes an even more distressing turn. Evidently Frankencarnie is the barker’s grotesquely deformed and mentally defective son, and this isn’t the first time Junior has done something fatal to somebody he was fixing to fuck. The barker has just begun to ponder how to cover up the big lug’s latest crime when Richie’s cigarette lighter falls out of his pocket and through one of the gaps between the floorboards, to land practically at the scheming man’s feet…

Each entry in Hooper’s redneck trilogy sets a bigger plausibility challenge for itself than the last, because each successive maniac or nest thereof has a more demanding lifestyle with regard to behaving themselves in public. In The Texas Chainsaw Massacre, Leatherface and his clan live on a farm a hundred miles from nowhere. Not only are they far out of sight on their horrible homestead, but they’re self-sufficient enough that only the patriarch has any need to leave it most days. In Eaten Alive, the Starlight is the cheapest hotel in town— the kind of place whose clientele would mostly not be missed by the outside world if they were to vanish one night down a hungry crocodile’s gullet. Nevertheless, the proprietor’s livelihood still depends on his ability not to scare away at least the occasional customer, so there’s a limit to how obviously revolting he and his flophouse can be. As for the carnival in The Funhouse, hundreds of people pass through it every single day during the operating season. At a minimum, the funhouse barker’s freak son has to be relied upon not to kill the overwhelming majority of them, the overwhelming majority of the time. Hooper was more successful on this third try than he was on the second. Whereas it was extremely difficult to believe that anyone with any other options— including just sleeping in the goddamned car— would ever take a room at the Starlight, The Funhouse presents its killer with a situation never envisioned by the people who’ve been covering for him. Its conflict is actuated by the protagonists doing a flagrantly stupid thing that most people in their position would not even consider. Unfortunately, there are two downsides to that generally laudable framing. First, it means that The Funhouse has to spin its wheels for an awfully long time while Amy, Buzz, Liz, and Richie work up the nerve to do that stupid thing. And second, the decision to stow away overnight in the funhouse is so self-evidently dumb that all but the most soft-hearted viewers are apt to write off the whole story as a case of natural selection in action.

Another bit of credit that I’ll extend to The Funhouse is that whatever else it may be, it definitely isn’t the by-the-numbers slasher movie that I went in expecting. Don’t get me wrong, it does check all the boxes— masked killer, Final Girl, characters finding the bodies of earlier victims, and so on— but you might say it checks them crooked, and in funny-colored ink. As one of the innovators of the form, Hooper rightly feels no obligation to conform to structural standards put in place by his imitators; he sets about winnowing the cast when he’s good and ready, and not a moment sooner or later. Amy is atypical of Final Girls, insofar as she’s no more cautious, clever, or resourceful than her friends who don’t survive the night. Mostly, she’s just lucky with regard to when, where, and how the killer catches up to her: after he’s already been seriously injured, in a space filled to brimming with deadly hazards for someone as large and clumsy as he is, under circumstances that allow Amy to keep one or more of those hazards in between him and her at all times. The killer has an unusual quality, too. Most of his ilk are loners, but the funhouse freak has a peer group, some of whom know what he is and cover for him, while others are apparently in the dark. That enables Hooper to provide a motive for the murders that one doesn’t see often in slasher films, or indeed in the horror genre generally. The funhouse freak isn’t out for revenge, or for kicks, or to defend his territory against intrusion. Strictly speaking, killing Amy and the others isn’t even his idea. Instead, he is set on them by his father, who needs them silenced in order to cover up the unrelated manslaughter that they accidentally witnessed.

Unfortunately those small and subtle virtues don’t go very far toward redeeming this rather tedious and directionless film. In theory, it makes sense that Hooper and screenwriter Lawrence J. Block wouldn’t want to dive straight into the murder and the mayhem. Like I said, there’s a fairly high plausibility hurdle to clear, and the easiest way to manage that is to spend some time showing the carnival just being a carnival. The Funhouse takes that rather too far, however, playing chicken with the limits of audience patience. It doesn’t help, either, that for a second time, Hooper brings in William Finley for a scene-stealing cameo that cues you to begin immediately imagining a more interesting and entertaining movie than the one he actually made. The most irritating thing about The Funhouse, however, is Joey. Everyone in this movie is personally repellant to one degree or another, but this asshole we meet while he’s committing what is arguably a sex crime against his sister. Only the funhouse freak and his dad are unambiguously more loathsome than that. And what’s worse, Joey is entirely irrelevant to the rest of the story, except during one scene. The latter occurs when his parents come to collect him at the carnival owners’ summons, introducing a fragile and ultimately false hope that Amy and her friends might be rescued as well. Otherwise, every second of screen time spent following the kid around (and believe me, there are a lot of those during the first two acts) is a second utterly wasted. That’s unforgivable in a movie already so inclined to lollygag.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact