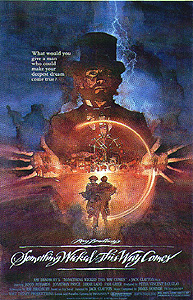

Something Wicked This Way Comes (1983) ***

Something Wicked This Way Comes (1983) ***

As I explained at some length while reviewing Fahrenheit 451, Iím mostly not a fan of Ray Bradbury. I make a big exception for Something Wicked This Way Comes, however. Something Wicked This Way Comes is one of those rare and magical cases where style and subject matter dovetail so perfectly that even the authorís most serious weaknesses are transformed into strengths. Its premise and perspective not only tolerate, but demand a writer whoís sentimental, old-fashioned, childishly earnest, and uncritically in love with the American small-town lifestyle. Itís the book Bradbury was born to write, and one of the finest coming-of-age horror stories ever told. It was also the perfect property for Walt Disney Productions to adapt during their early-80ís dark period, one that should have brought out all the virtues of that often disappointing effort to shift the studioís brand identity. Disneyís Something Wicked This Way Comes didnít quite live up to that promise, but it stands head and shoulders above the likes of Tron and The Black Hole just the same.

Greenwood, Illinois, is by no means a happening town, but itís hardly the middle of nowhere, either. At the very least, itís big enough to merit its own library, along with more common amenities like a school, a bar, a cigar store, and a barber shop. Indeed, you might say that Greenwood is just big enough and just sophisticated enough to foster discontent among its inhabitants that it doesnít have more to offer. For instance, Tetley the tobacconist (Jake Dengel, from Prayer of the Rollerboys and Bloodsucking Pharaohs in Pittsburgh) is chronically frustrated by the limited demand for his wares, which has stymied his every effort to take his business upscale. Meanwhile, Crosetti the barber (Richard Davalos, from The Cabinet of Caligari and Legacy of Blood) is a lonely man whose fantasies of romance with exciting, exotic women will never be fulfilled by any of the prosaic local ladies. Other Greeenwooders are beset by longings and regrets that would no doubt remain with them no matter where they lived, like Miss Foley the schoolteacher (Mary Grace Canfield), who blundered into a life of spinsterhood despite having once been the most beautiful and desirable girl in town, or Ed the bartender (Double Exposureís James Stacy), a former college football hero who lost his left arm and leg in some manner of accident. Librarian Charles Halloway (Jason Robards, of A Boy and His Dog and the 1971 Murders in the Rue Morgue) is in the latter category, too. His big regret is that heís so damned oldó too old to be the kind of active, hands-on father he believes his son, Will (Wizards of the Lost Kingdomís Vidal Peterson), deserves. Nobody in Greenwood is more discontented, however, than Willís best friend and next-door neighbor, Jim Nightshade (Shawn Carson, of The Funhouse). Practically all Jim ever thinks about is growing up and getting out, as far away from sleepy little Greenwood as possible, and never looking back. Heíd be doing no more than to take after the father he never met, who ran off to who knows where when Jim was just a tiny baby.

There are things in the world that can smell human dissatisfaction a thousand miles away, and in the small hours of one cold October morning, a pack of such creatures descends upon Greenwood in the form of Darkís Pandemonium Carnival. Together with his associatesó principally the strongman Mr. Cooger (Bruce M. Fischer, from the ďRoger Corman PresentsĒ version of Humanoids from the Deep), a seductive fortune teller (Pam Grier, of Sheba, Baby and Women in Cages), and a gang of dwarves led by Angelo Rossitto (whom weíve seen before in Galaxina and Fairy Tales)ó the eponymous Mr. Dark (Jonathan Pryce, from Stigmata and Brazil) will tempt the people of Greenwood with all the things they canít seem to have, capturing the souls of each as they succumb to his diabolical generosity. Will and Jim, inevitably, are the ones who figure out that the carnival is more than natural. Sneaking about the grounds after hours on its first day of operation, they catch Mr. Dark using the enchanted carousel (which was supposedly out of order during the day) to regress Mr. Cooger to childhood so that he can make malicious mischief in the town unrecognized. The boys get caught snooping, and thus become priority targets for Dark and his minions. Another priority target, oddly enough, is an eccentric traveling lightning rod salesman by the name of Tom Fury (Royal Dano, of Killer Klowns from Outer Space and Drum). Fury claims to have a preternatural understanding of thunderstorms, and thunderstorms, of all things, are the carnivalís secret weakness. Rain dispels the demonic entertainersí magic, and lightning can actually destroy them, so it behooves Dark and his followers to steer clear of such weather. If Fury is to be believed, a powerful storm is gathering right on top of Greenwood, but only he knows when it will break. If Dark could add Fury to his staff of soulless slaves, heíd be the next best thing to invulnerable. In the meantime, though, the more pressing need is to prevent Will and Jim from enlisting the aid of some adult with sufficient imagination to believe their tales of what really goes on at the carnival. Clearly the most promising angle of attack there will be to prey on Jimís own restlessness, and Will thus finds himself in a desperately uneven battle for his friendís soul.

The mere fact that the child most susceptible to the allure of Darkness is called Jim Nightshade should be enough to tell you that Something Wicked This Way Comes is about as subtle as a quarter-stick of dynamite. But thatís about how subtle life is when youíre twelve or thirteen years old, too, so the heavy authorial hand often works in the movieís favor. The viewpoint characterís age also goes a long way toward justifying the filmís extreme sentimentality and headlong eagerness to buy into the myth of the small-town Good Old Days. Mistaking the carefree simplicity of childhood for an accurate reflection of the past is pretty much the whole reason why nostalgia even exists, the movieís blatantly nostalgic treatment of Greenwood and its inhabitants is a good shorthand strategy for aligning our perspective with Willís. The same can even be said for the strangely limited effect that Willís actions have on the larger story. He can steady the two most important people in his lifeó Jim and his fatheró against the seductions of the evil carnival, but actually driving Mr. Dark and the others out of Greenwood is far beyond his power. The best Will can do there is to keep one step ahead of the demonic forces until Tom Furyís delivering thunderstorm finally deigns to show up. Again we have a sturdy allegory of late childhood and early adolescence, when sometimes the only solution to a problem is to survive long enough for the deus ex machina of adulthood to sweep it away. Mind you, thatís not how it worked in the book, which gave the carnival people an altogether more prosaic (but also altogether more logical) weakness that Will and his father were capable of exploiting directly. Some trace of that vulnerability is still visible in the film, possibly as a fossilized holdover from an earlier draft of the screenplay, but itís so faint that viewers unfamiliar with the novel may not even notice its presence. I find Bradburyís original ending more dramatically satisfying, although the replacement does tie in well enough with the storyís themes that trading in the heroesí agency for a big, flashy set-piece does less damage than youíd normally expect.

It also helps that Something Wicked This Way Comes is exceptionally well cast. Truth be told, thatís something that most of the Dark Disney movies had going for them, but itís especially noteworthy in this case because good juvenile actors are so persistently hard to find. Will could easily have been a pretty boring character, since his goodness is basically the entire point of him. What stops him from being so is his friendship with Jimó no one willing to be masterminded into mischief by the likes of Jim Nightshade can be a complete goodie two-shoesó and so the credibility of that friendship becomes the key to our acceptance of the storyís central figure. Vidal Peterson and Shawn Carson have by far the most easy and natural-seeming relationship in a movie chock full of deliberate artificiality, and in some ways make it possible for all that artificiality to succeed. As for Jason Robards, itís a pleasure to see him in such a nuanced, multifaceted role at a point in his career when he seemed to spend most of his time playing one largely interchangeable grouchy old man after another. The real show-stealer here, though, is Jonathan Pryce. Thatís hardly surprising, since itís pretty much always the villain that you remember best in a horror film, but Pryce really does gobble up all of your attention here every time he appears on the screen. Whatís all the more impressive is that itís an underplayed performance for the most part, with only one scene where he really cranks up the intensity level. Except for the confrontation between Dark and Charles Halloway in the library, Pryce is all stillness, quiet, gentleness, and ingratiation, but his demeanor still reads as absolute evil. That Mr. Dark is not remembered today as one of the iconic Disney villains may convey some sense of the ambivalence with which the studio and its fans regard this phase of the companyís history.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact